- Catalog No. —

- Mss 2204

- Date —

- 1831

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement)

- Themes —

- Oregon Trail and Resettlement

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Research Library

- Regions —

- Oregon Country Oregon Trail

- Author —

- American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory

American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory

The mythology that (mis)characterizes the American settlement of the West as an epic tale of virtuous triumph over a dangerous and exhilarating wilderness was fueled in part by reports from early explorers. But the notion that journeying to the West was a moral struggle of epic consequences, made profound by American exceptionalism, most often came from the imagination of writers, poets, politicians, and enthusiasts who had never made the trip. For those who did travel to the West in the early and mid-nineteenth century, the romance of the journey (though not always completely lost) was dissipated in the face of difficult terrain, extreme weather, disease, and the tedium of a strenuous and ongoing daily routine. Significantly, overlanders were disabused of their preconceptions of Native people, who were more likely to aid and observe their journey than attack without provocation.

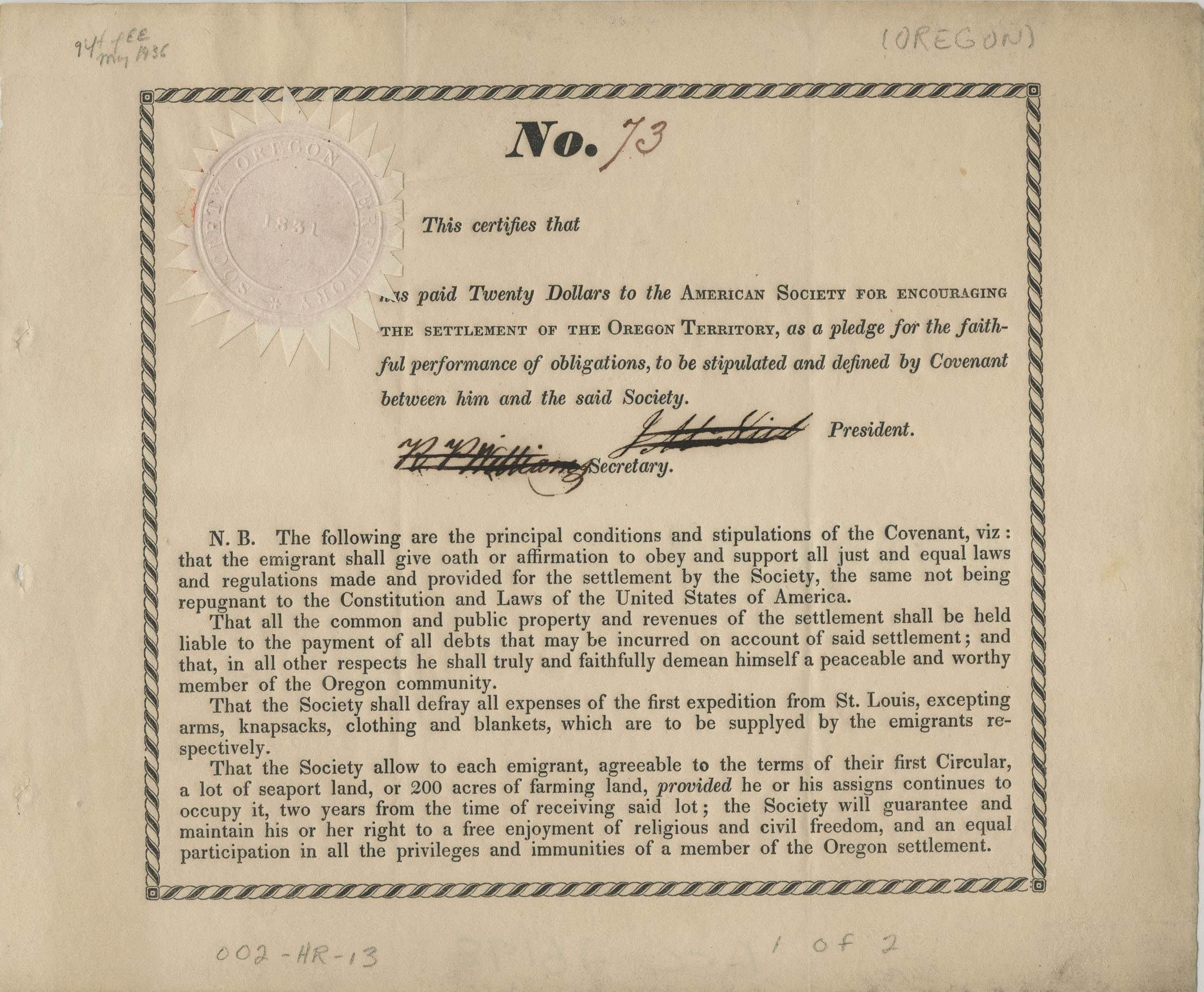

The hopes and fantasies of these romantics-turned-realists live on in historical archives. This certificate, held by the Oregon Historical Society Research Library, was issued in 1831 by the American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory. Its purchaser was supposedly eligible for guided and subsidized transportation to the Oregon Country, where parcels of land awaited to be claimed and “improved.”

The Society was the invention of Hall Jackson Kelley, a writer from Boston who was fascinated with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He devoted himself to promoting the American colonization of Oregon and had visions of a grand city at the intersection of the Columbia and Multnomah (now Willamette) Rivers. When his petitions to Congress for financial, military, and legal support failed, Kelley used the Society to recruit and fund an overland expedition he hoped to organize. For twenty dollars, emigrants could join a company of fifty people led by an experienced guide. Kelley emphasized the need for people of "good morale [sic] character” who had useful skills, such as carpentry and medicine. He was excessive in his praise of Oregon and of the people he wished to colonize it with, mainly, white American Protestants:

"The uniform testimony of an intelligent multitude have established the fact, that the country in question, is the most valuable of all the unoccupied parts of the earth. Its particular location and facilities, and physical resources for trade and commerce; its contiguous markets; its salubrity of climate; its fertility of soil; its rich and abundant productions; its extensive forests of valuable timber; and its great water channel…are sure indications that Providence has designed this last reach of enlightened emigration to be the residence of a people, whose singular advantages will give them unexampled power and prosperity." (From Kelley's Memorial to Congress, 1829.)

Kelley's enterprise was unrealistic, perhaps most practically because the United States had no legal jurisdiction to issue deeds to land claims in Oregon Country. Kelley had asked Congress to grant American settlers the right to extinguish Native titles to land, but the U.S. had no authority to do so in Oregon. The U.S. had agreed in 1818 to joint occupation of the region with Great Britain (an agreement that held until 1846), and people in Oregon Country conducted their own land transactions, without legal authority. The few non-Native settlers in the Willamette Valley were Hudson’s Bay Company retirees, who had negotiated for Oregon land either through kinship ties with their Native wives or by squatting on claims they hoped would one day be recognized by a government.

Even the name of the society was a pipe dream—the United States and Britain had stalled in their most recent occupation negotiations, in large part because the British-owned HBC had become the dominant foreign presence in Oregon Country, challenging American claims of “discovery” based on Robert Gray’s inaugural trip up the Columbia River in the Columbia Rediviva in 1792. Both countries held on to access to the region's resources, and it was unclear in the 1830s whether the U.S. would ever establish sovereignty over the region, let alone create territories.

Kelley was also slowed by an unenthusiastic response to his plans and negative coverage by the press, which referred to him as an "idle schemer." The route to Oregon was a decade away from being a well-traveled trail, and Americans still imagined the Oregon Country as a dangerous wilderness, marred by "starvation, torrential rivers, hostile Indians, wild animals, and winter in the mountains." Despite having never traveled west of the Mississippi River, Kelley wrote and published A Geographical Memoir of Oregon, which provided a map and travel guide, to generate support. The enthusiastic pamphlet attracted some emigrants, but not enough. Kelley’s planned expedition was pushed to 1833.

Kelley eventually abandoned his overland route through the Rockies and headed to Louisiana to meet up with traveling companions, who subsequently stole from him and abandoned the trip. From there, he sailed to Mexico, where his property was seized by the Custom House. He recovered a portion of it, and by foot, mule, and horse spent weeks traveling through Mexico, at one point (by his own account) tangling with robbers. He arrived in San Diego on April 14, 1834, where he met Ewing Young, who would have his own profound impact on Oregon colonization when his intestate death prompted the creation of the Provisional Government in 1843. The two men agreed to travel together on the final leg to what Kelley called "the land of my hopes." By the time they reached the Sacramento Valley, Kelley was sick with malaria.

At last, Kelley arrived in Oregon Country very ill, "shaking like an aspen leaf" and falling from his horse. With the help of Umpqua tribal members, he and Young reached Fort Vancouver on October 27, 1834, where they were hospitably tended to (an irony, given that Kelley had often publicly denounced the HBC as a foreign threat to American interests). When John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of the HBC, received word that Kelley and Young had been involved in cattle rustling in California (a charge Kelley blamed on a group of "marauders" who had joined their traveling company, accusing McLoughlin of using the claim as an excuse to keep the Americans out of Oregon), the Americans were told to leave the fort. After Kelley spent a few months surveying the lower Columbia, the hostility from McLoughlin and the indifference shown him by the few Americans in the region (including Young) convinced him that it was time to leave. McLoughlin arranged for Kelley to sail to Hawaii in March 1835, where he found passage to Boston. His grand adventure was over.

Kelley continued to write about Oregon, and he reportedly inspired others to travel to the West, including Benjamin Bonneville. Bonneville, a military officer on leave of absence, led a 110-man detachment in one of the first exploratory American crossings of the Continental Divide in 1832. Kelley is also credited with inspiring missionaries Jason and Daniel Lee, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and Henry and Eliza Spalding to venture west, as well as naturalist Thomas Nuttall.

The American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory folded, and its certificates became collectors items. The signatures of the Society’s president, John McNeil, and secretary, Robert P. Williams, have been “ink cancelled” on the remaining documents, including this one, to indicate they were not valid.

Further Reading

Powell, Fred Wilbur. "Hall Jackson Kelley, Prophet of Oregon." Oregon Historical Quarterly 18, no. 1 (1917).

Kelley, Hall Jackson. A Geographical Sketch of Oregon. Boston: J. Howe, 1830.

Kelley, Hall Jackson. A Narrative of Events and Difficulties in the Colonization of Oregon. Boston: Thurston, Torry & Emerson, 1852.

Written by A.E. Platt, © Oregon Historical Society 2021

Related Historical Records

-

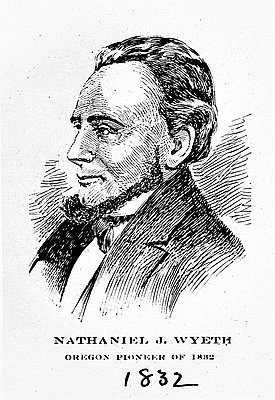

Nathaniel Wyeth's expeditions to Oregon

A businessman from Cambridge, Massachusetts, Nathaniel Wyeth played an important role in the Euro American colonization of the Pacific Northwest. As a result of his efforts to establish trading operations …

-

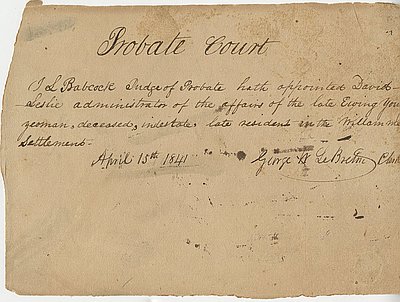

Probate Court: David Leslie assigned executor of Ewing Young's estate

This scrap of paper—handwritten, covered in centuries-old smudged fingerprints—is a remnant of the first significant attempt to create a functioning non-Native government in Oregon Country. The four men …

-

Rev. Jason Lee's Diary

­­­This is the diary of Rev. Jason Lee (1803-1845), one of the first Methodist missionaries to travel on the Oregon Trail and settle in Oregon Country. Like all of …