- Catalog No. —

- Gi 7492

- Date —

- n.d.

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration), 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River

- Author —

- Benjamin Gifford

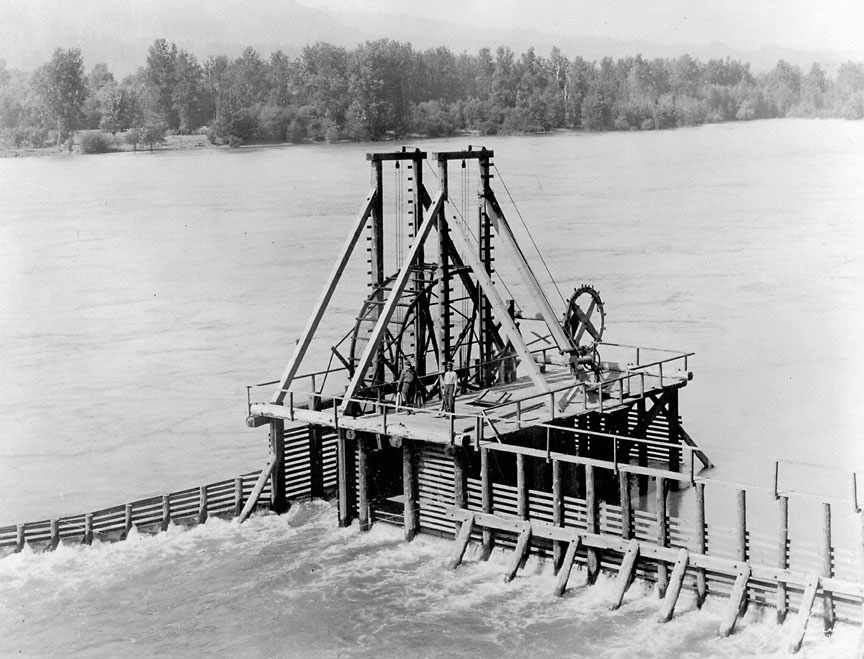

Columbia River Fish Wheel

This undated photograph of two men standing on the deck of a stationary fish wheel was taken by Benjamin A. Gifford, a professional photographer working from Portland, Oregon.

While archaeologists have dated Columbia River salmon harvests back 10,000 years, it wasn’t until the growth of the salmon canning industry on the river, beginning in 1866 with the construction of Hapgood, Hume and Company’s cannery, that substantial numbers of salmon began to be harvested by non-Indians. Cannery construction expanded until markets were saturated in 1883, when the combined production of thirty-nine Columbia River canneries exceeded 42,000,000 pounds. After the peak years of the early 1880s, the Columbia River salmon industry began a slow, uneven decline, marked by periodic upturns in the harvest, and by a second peak in production during World War I.

Canneries owned most of the fish wheels on the Columbia River. Their design was simple: powered by the downstream rush of the river, huge wooden and wire baskets continually scooped through the water, picking up migrating adult salmon that were moving upstream. The fish found themselves funneled into the wheel by weirs, the wooden fences in the photo that extend into the river. Once fish were scooped out of the river, the wheel dropped them into a “fish box,” which was a holding pen or cage. In order to remove the salmon from the fish box, the wheel’s operator(s) climbed down a ladder from the deck (see photo for opened hatch in deck) and speared the fish with a long pike. The fish were typically hauled above deck in a small elevator powered by a hand-crank. Fish wheels were used in the shallow, fast-moving waters of the Columbia River from 1879 until 1934.

Fish wheels were not popular with other fishers on the Columbia. Downriver commercial fishers resented their use and accused fish wheel owners of exhausting the river’s salmon fishery. Indian fishers found themselves dispossessed of traditional fishing sites by fish wheel owners, and successfully fought for their removal through the legal system. Sport fishers also railed against their use, arguing that the only way to honorably catch salmon was with a hook and line.

Conflicts between competing fishers became increasingly more public by the twentieth century. In order to harness public sympathy for statewide votes, fishers called on voters to outlaw their opponent’s gear in the name of “conservation.” As the public became more aware of the ever-shrinking numbers of salmon returning to the Columbia River, they responded to calls for conservation by passing a number of regulatory laws to govern the salmon fishery of the river and its tributaries. Voters passed laws that prohibited the use of fish wheels in Oregon in 1928 and in Washington in 1935.

Further Reading:

Donaldson, Ivan. Fishwheels of the Columbia. Portland, Oreg., 1971.

Seufert, Francis. Wheels of Fortune. Portland, Oreg., 1980.

Smith, Courtland L. Salmon Fishers of the Columbia. Corvallis, Oreg., 1979.

Written by Joshua Binus, Oregon Historical Society, 2003.

Related Historical Records

-

Old Fishwheel on Klamath River, 1905

In 1905, wildlife conservationists William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman camped in the Klamath Basin to photograph waterfowl traveling along the Pacific Flyway. Hiking near the banks …

-

Eagle Cliff Cannery

This photograph shows the Eagle Cliff Cannery, located on the Washington side of the Columbia River about fifty miles upriver from Astoria. During the winter of 1866-1867, brothers …

-

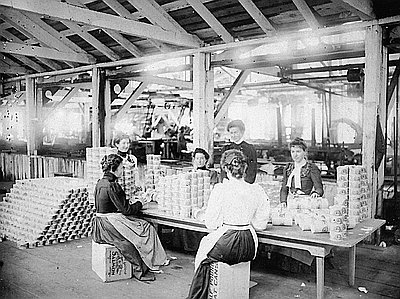

Women Cannery Workers

This photograph was taken by Portland photographer John F. Ford, probably between 1900 and 1902. It shows women labeling cans of salmon at the Megler Cannery in Brookfield, …