- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 89369

- Date —

- 1886

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Geography and Places, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- West Shore Magazine

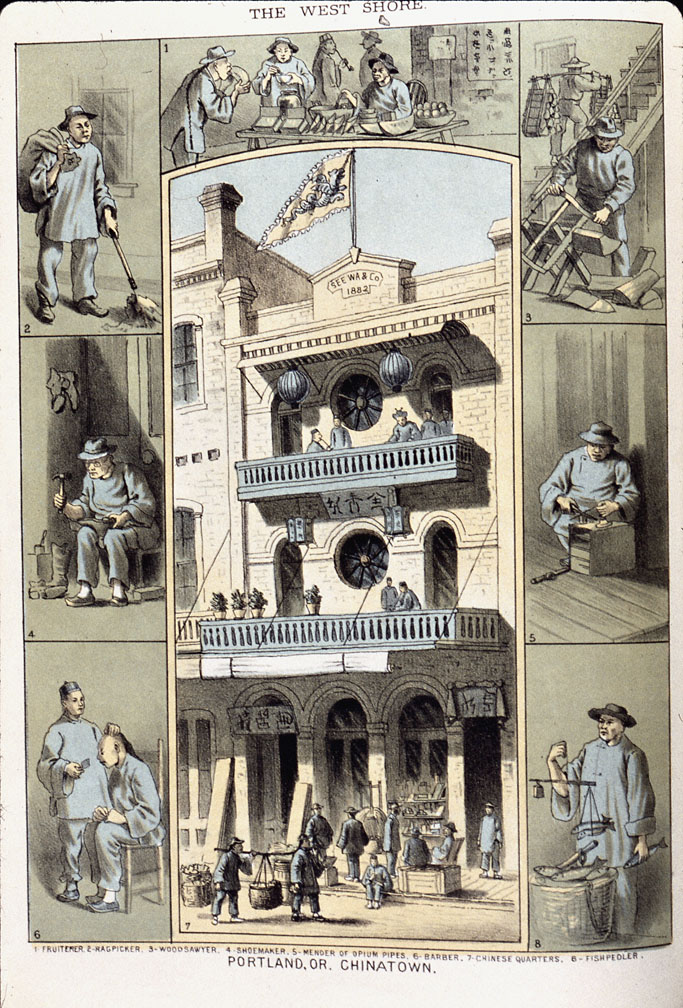

Portland Chinatown, 1886

This color lithograph accompanied an article titled “A Night in Chinatown” in the October 1886 issue of West Shore, a Portland news and literary magazine.

Several thousand Chinese lived in Portland in the 1880s, most of them unmarried men who plied a variety of occupations, as depicted in this illustration. Most lived in two enclaves: an urban Chinatown which extended along what is today SW 2nd Avenue between Taylor and Pine streets, and a community of vegetable gardeners who lived and farmed along the banks of Tanner Creek in the vicinity of SW 19th and W Burnside and PGE Park.

The urban Chinatown consisted of retail shops, residential apartments, temples, and meeting and gaming rooms that occupied buildings leased from white landlords. The See Wa & Company building, built in 1882, is an ordinary three-story commercial building with modest Italiante detailing, such as the arched entries on the first floor, probably with cast iron columns, and the similarly arched windows above. But the tenants have added a number of touches, such as the two exterior balconies, the curved metal awning on the third level, the pennant and lanterns. The round windows are very unusual, and may be adaptations as well. Balconies were a common marker of Chinese quarters in cities and towns. One extant example in Portland, the Waldo Block at SW 2nd Avenue and Washington Street, has a recessed balcony that was added to the third floor of the 1886 Italianate commercial block in 1920. Chinese tenants also frequently altered interiors, adding rooms, half-stories, and passageways to make intensive use of the space.

The buildings in the Tanner Creek gardens area were vernacular wooden dwellings built by the Chinese. They were “apparently near exact duplicates of the pitched-roof, simple wooden structures that were and are a part of rural Chinese buildings,” according to historian Marie Rose Wong. “The combination of broad overhangs on houses built close to one another created covered walkways, a useful feature during Portland’s rainy winter months. Without the obvious Asian motifs and decorative colors, however, Portland society dismissed the community as nothing more than a slum.” The gardens gave way to development early in the twentieth century. Much of downtown Chinatown migrated north in the 1920s and 1930s, adjacent to the area known as Nihonmachi or Japantown, and generally then known as the North End. Today the distinctive balconies and colors persist in a neighborhood labeled Old Town.

Further Reading:

Wong, Rose Marie. Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: the Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon. Seattle, Wash., 2004.

Related Historical References:

National Register of Historic Places: Oregon—Multnomah—Portland New Chinatown--Japantown Historic District (#89001957). Also known as Chinatown National Register Historic District. Bounded by NW Glisan St., NW 3rd Ave., W. Burnside St., and NW 5th Ave., Portland.

National Register of Historic Places: Oregon—Multnomah—Portland Skidmore/Old Town Historic District (#75001597). Also known as Skidmore/Old Town Historic District. Roughly bounded by NW/SW Naito Pkwy., NW Everett St., NW/SW 3rd Ave., and SW Oak St., Portland.

Written by Richard Engeman, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.