A Workers' Paradise in the Pines

Working people in central Oregon’s towns were likely to be employed by the lumber industry or an affiliated business. These were the largest employers. During the two world wars, women worked in the mills and box factories. Tradesmen such as electricians, pipe-fitters, boiler makers, and carpenters were well-compensated. So were the specialists, like the sawyers who operated the giant head-rig saws, the lumber graders, and the mill production managers. These people were part of the region’s emerging middle class. On the white-collar side, the mills needed engineers, accountants, publicists, and other office workers. The lumber business required an army of salesmen to “move” the lumber to customers in other parts of the United States.

For laborers and tradesmen employed in the mills, life in a central Oregon industrial town had some real appeal. “Family men,” as married workers were called, could enjoy a comfortable life with regular wages, medical and disability services, and a modest home of their own. They were likely to live in a bungalow within walking distance of the mills. The smell of pine sawdust permeated the air, and the mills’ whistles punctuated each day. Schools, churches, and sporting organizations dominated the workers’ social life, and all of these institutions benefitted from the lumber companies’ largesse.

For single men, living accommodations were available in rooming houses, boarding houses, and residential hotels. Although we tend to lump these categories together now, the distinctions were important to workers in the 1920s and 1930s. Rooming houses were family houses with an extra bedroom or two that rented by the month. Single people living there shared a bathroom with the family and had access to the yard and perhaps the kitchen as well. Boarding houses were like rooming houses, but the rent included meals, served “family style” for all the boarders and the family. Residential hotels offered separate rooms with more privacy, but did not provide meals. Residents of the hotels would have eaten their meals in a nearby café. Spring Street in Klamath, Bond Street in Bend, and similar zones in Prineville and Redmond catered to the single male workers. In such places, drinking, gambling, and prostitution flourished.

Oregon novelist H.L. Davis was born in Yoncalla, but spent much of his early life in central Oregon. Davis’s career as a novelist and essayist spans the critical decades of the industrial period. He set much of his fiction in the 1920s and often made his characters frustrated farmers and stockmen trying to live with social changes that made their skills obsolete. For example, all though Davis’ novel Winds of Morning, the central character tends a recalcitrant herd of work horses that he has assembled from abandoned farm stock. No one fails to comment on how worthless the horses have become since the farmers have all bought tractors. At the end of the novel, set in about 1920, the market for wheat has collapsed and the farmers can no longer afford gasoline, so the horses are again valuable. Davis’s characters are drawn from central Oregon’s working classes, and his places are thinly-fictionalized central Oregon locales. Davis won the Pulitzer Prize for his fiction, and national magazines published his central Oregon essays as late as the mid-1950s.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

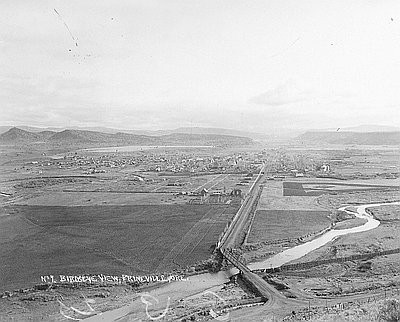

Bird’s-eye View of Prineville, c. 1915

This bird’s-eye view of Prineville, Oregon was taken by Charles Wesley Andrews (1875–1950) around 1915. The photograph looks east down Main Street. Ochoco Creek is visible passing through …

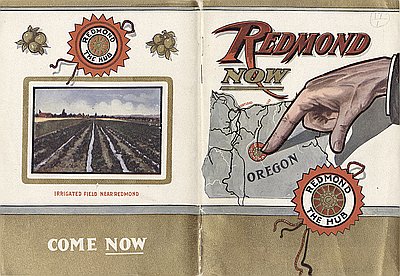

Redmond Now, Promotional Pamphlet

This promotional pamphlet of Redmond, Oregon was co-published by Southern Pacific and the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company in 1910. The railroad companies hoped to attract settlers to …