Columbia Legacies

In the end, the significance of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its personnel is an open and contested matter. Those who find it preeminently a story of adventure, achievement, and nationalistic accomplishment have plenty of drama to support their viewpoint. Those who see it as part of a long history of paternalistic and damaging engagements with Indian people in the Northwest can cite incident upon incident where the explorers appear arrogant and dismissive of Native people. To modern readers of the Journals, the ethnocentric attitudes so evident in Lewisand Clark’s encounters with the Native nations appear obvious and bound to fail, but in the context of the Enlightenment and its assumptions about the power of science, rationality, and republican politics the explorers’ attitudes are perhaps more understandable.

Nonetheless, there is no avoiding the sweep and enormity of change that has occurred in the Columbia River Basin since Lewis and Clark visited some two centuries ago. The Native populations in the region live on a much smaller landscape and not necessarily of their choosing. Within half of a century of Lewis and Clark’s exploration, they had lost their legitimate claim to a vast region and with it the opportunity to live as they had for thousands of years. The loss came in the face of a juggernaut, the steady settlement of the region by a determined, powerful, and wealthy population.

The Columbia River itself is not recognizable. Nearly every activity in the region today can be tied in some way to modern uses of the river, especially the production of hydroelectricity and the irrigation of millions of acres of farmlands. Primary among the changes to the river are the machines that impound, channel, and sluice the water, changing the Columbia from a seasonally and wildly fluctuating stream to a steady and nearly predictable provider of benefits. The benefits of these developments are undeniable, but the environmental and social costs cannot be overlooked, and in essential ways those costs have become significant and central public policy issues. A most glaring cost is the diminishment of salmon runs and the loss of Indian fishing grounds, two conditions that many in the region work to redress.

Lewis and Clark cannot lay claim to the benefits of changes in the Columbia River Basin and they cannot be blamed for their costs. Their expedition played an important role in Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, both as a fulfillment of his deepest desires for knowledge about the West and as a contribution to his vision for the region. There is little doubt that the fur trade, the exploitation of natural resources, and the broader development of the American West would have taken place with or without Lewis and Clark’s achievements. There is also little doubt that the United States would have prevailed in its competition with Britain for control of the Northwest, with or without the additional claim the Lewis and Clark Expedition made on the territory.

Nonetheless, this saga of exploration has laid a claim on the American imagination, because of its boldness and the enormity of the territory it crossed. It is a big story, but like all big stories in our past, it inspires claims greater than it can justify, while it justly invites us to learn about this nation and its deeds by finding out what happened and why we think it important. In this way, the Lewis and Clark Expedition deserves its place in the pantheon of American experiences. In the twenty-first century, it invites everyone to adopt the broadly inquisitive approach of the explorers as we try to understand our place in the world.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

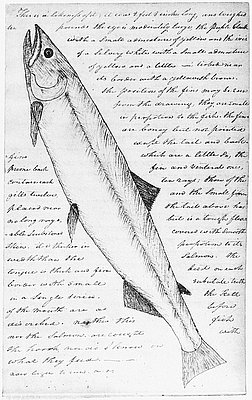

Clark's Drawing of White Salmon Trout

This is a copy of a sketch made by William Clark in February 1806, while Expedition members were at Fort Clatsop near the mouth of the Columbia River. …

Estimate of Western Indians, Lewis and Clark Journals

Charged by Pres. Thomas Jefferson with recording the names of Native communities and estimating the size of their populations, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark took note of …

Meriwether Lewis to Thomas Jefferson, 1805

Captain Meriwether Lewis wrote this letter to President Thomas Jefferson in early April 1805 from Fort Mandan, near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. It was hand-copied and the spelling corrected …