Farming Tule Lake

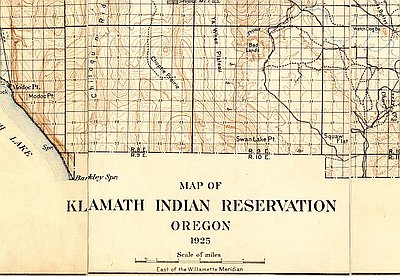

John Staunton’s father was a West Virginia stockbroker who came to the dry climate of this region for his health. As a veteran of World War I, Edward “Web” Staunton applied for a Klamath Project homestead. It was 1929. The New York stock market crashed, wiping Staunton out, and he became a full-time farmer.

The work agreed with him. John Staunton remembers that when he was five, his father grabbed a handful of wet soil and said, “Isn’t this great?” The boy felt a bond with his father and with the earth. “He raised me to be a farmer,” said Staunton, who has been farming in the Upper Basin all his life.

After World War II, farmers found a growing demand for their produce, with new families booming in the U.S., and war-torn countries across the Pacific needing American crops. All three of John Staunton’s sons became farmers.

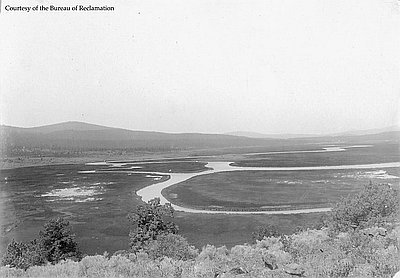

The costs of farming rose steadily. When John returned from the armed services in 1957, a new tractor cost less than $8,000. By the end of the twentieth century, the price was at least $60,000. Water politics, which made the Bureau of Reclamation cut back on the irrigators’ share of flows from Upper Klamath Lake in 2001, together with competition from a globalized agricultural market raised concerns about the future of the region’s family farms.

John Staunton insists that farming has a future here. He says that his potatoes yield double the national average in sacks per acre; that local wheat and barley have the best yield per acre in the western United States; that Upper Basin alfalfa hay is the best dairy quality; and the onions, which are dehydrated and consumed as onion salt, are excellent both in yield and quality. Even so, the days of the Staunton family farm are numbered. Staunton laments that none of his grandsons are interested in farming.

Bob Anderson is a World War II veteran who won his Klamath Project homestead in the postwar lottery. Born in Klamath Falls in 1920, he grew up on his family’s farm nearby. Anderson’s father had come there from Sweden via North Dakota. His mother, a millworker’s daughter, was raised in Grants Pass, Oregon.

The Andersons’ major crops were potatoes, wheat, and alfalfa. Bob remembers digging potatoes, which he put into sixty-pound sacks that his father threw onto a wagon; bundling wheat into stacks that were tossed into a threshing machine; and catching gunny sacks full of suckers with his dad. The fish got trapped in irrigation canals until recent years, when some of the farmers put in screens.

One day, when Bob was seven or eight, his dad was stacking hay when a horse kicked him in the nose, splitting his head open. The boy ran three miles to the neighbors, who took his father to the hospital. Not long afterwards, the Andersons bought their first tractor, switching from horses to horsepower.

In 1960, the Andersons were among the first in the region to make another technological change: from flood irrigation to sprinkler systems which conserve water. Bob’s son John, born in 1952, says that when he was growing up, “we always seemed to have plenty of water.” However, in 2001 when the Bureau of Reclamation, which had provided abundant water, closed the valves to the Klamath Project canals, the Anderson lands dried up. The loss of a growing year drove the family deeply into debt. To adapt, they switched from crops to cattle. This saves equipment costs and gives them flexibility in light water years. The Andersons continue to grow alfalfa hay, which they use to feed their herd of 1,000 cows.

Bob Anderson regrets the fact that alfalfa is hard on wildfowl. The swather cuts through nests that birds hide within that crop. The elder Anderson keeps an incubator to raise young birds and then he releases them near Upper Klamath Lake.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

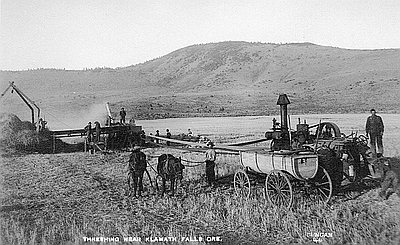

Threshing near Klamath Falls

This postcard shows farmers using a steam-powered thresher near Klamath Falls, which was originally called Linkville. In 1909, the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Klamath Falls, helping attract more …

Klamath Project Canal & Tunnel

Construction of the Klamath Reclamation Project, a federally constructed and managed irrigation system, began in 1906 with the building of the Main Canal, or “A” Canal, and tunnel. …

War Memorial, Lake County

This monument was erected at the Mitchell Recreation Area in the Fremont National Forest, Lake County, Oregon in memory of Elyse Mitchell and five children who were killed …