Restructuring the Timber Economy

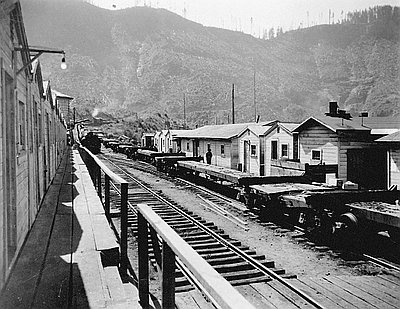

In October 1979, the bottom fell out of the wood-products market. Over the next three years, lumber prices dropped by more than 48 percent. The national recession of the early 1980s hit resource-dependent communities particularly hard. A wave of mill closures left many workers jobless, and the unemployment rate topped 25 percent in some coastal towns. The effects of the shutdowns rippled through coastal communities, bringing hard times to retailers and other businesses, slashing local tax revenues, and starving community service organizations. By the time the national economy recovered in the mid 1980s, forty-eight thousand jobs in the Pacific Northwest lumber industry were gone, most of them never to return.

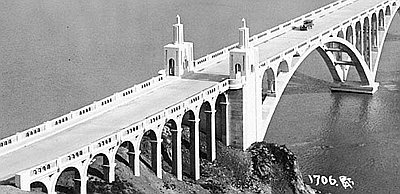

The recession triggered a shakeout during which companies downsized, merged, migrated, were swallowed by other companies, or went out of business. Georgia-Pacific, which had moved its headquarters to Portland in 1954, moved back to Georgia in 1982, and the green neon “G-P” logo atop the company’s landmark Portland office building winked out for the last time.

Several factors were responsible for the downturn. High interest rates in the early 1970s discouraged housing construction. Canadian lumber emerged as a competitive threat, and so did Southern pine, as the forests of the South, extensively logged between 1900 and 1950, once again began to produce harvestable timber. A market for Douglas-fir developed in Japan, boosting log prices and making it more profitable for companies to export logs than saw them into lumber at local mills.

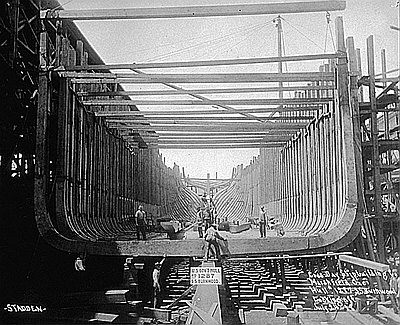

Finally, many Northwest mills built in the 1950s or earlier were reaching the end of their productive life. To stay competitive, companies had to invest in expensive equipment upgrades and new technology. The companies that survived the shakeout made these investments and improved their productivity to the point where they needed far fewer workers than in the past.

Adding to the general instability was the fact that the industry had become dependent on federal timber. In 1952, the peak year for timber harvest in western Oregon, about one-third of the 10.4 billion board feet harvested came from U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management land. In 1963, for the first time, more timber was cut on federal than on private land. Federal and private harvests were roughly even (averaged over the years) until 1990, when a landmark event shut off much of the federal timber pipeline.

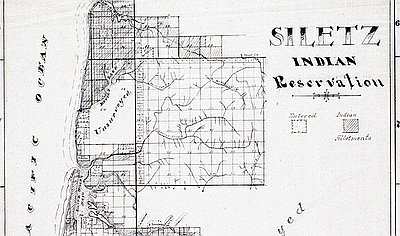

By the end of the 1980s, the environmental battleground had moved into the federal forests, and timber sales were being halted or dragged out by appeals and lawsuits. In July 1990, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service handed the environmental movement a victory when it identified the northern spotted owl as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The listing meant the owl’s habitat of old-growth forest had to be protected. Soon after the listing, a federal judge stopped timber sales on national forests and BLM lands in western Oregon. Loggers were mocked and insulted in some environmentalist newsletters, and bumper stickers were seen on pickup trucks that read, “I love spotted owls...fried.”

President Bill Clinton convened a team of biologists, economists, and social scientists in Portland and charged them to find a way to allow for some logging of federal forests while preserving enough habitat for imperiled or sensitive wildlife. The 1994 Northwest Forest Plan, under which federal forests in the Northwest are now managed, protects up to 80 percent of old-growth forests and sets harvest levels on the rest at 1.2 billion board feet a year—a decline of 70 percent from 1970s levels.

The Northwest Forest Plan was supposed to be a compromise between traditional resource-use interests and environmental interests, a way to halt environmental lawsuits and let timber harvesting proceed, although at reduced levels. But the timber industry has not been happy with the harvest, which has been well below 1.2 billion board feet, and the environmental community has not been happy with the plan's provisions to protect wildlife. The lawsuits have continued, and the plan remains controversial.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.