Written by Michael N. McGregor

We know him only from the ship's log, a single notation that tells us a "Mr. Jones" spent seven months onshore recovering from an unknown illness. Yet he may have had a significant impact on Oregon history, bringing with him a disease that left 90 percent of Lower Columbia River Indians dead, and whites as Oregon's new majority.

It was August 4, 1829, when the Indians saw what looked like a big black canoe, the Boston trading ship Owyhee, cross the Columbia bar and eventually moor in Multnomah Channel. They had seen this ship once already and dozens of others like it going back to before 1792 when American Robert Gray gave their river a foreign name. They had seen death come in the wake of a ship's departure before, too. In 1775, shortly after a Spanish galleon left the Columbia, many of them died from what they called "skin sick." A vicious disease that caused "little mouths" to open all over the body, "skin sick" — which the whites called smallpox — killed a third of the Lower Columbia Indians.

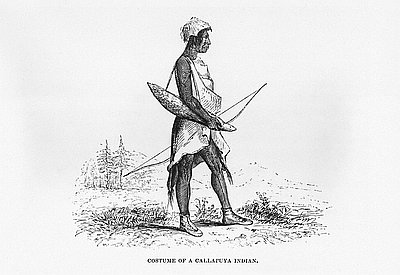

The Indians, mostly Chinook and Kalapuyan, knew why the Owyhee was there. For years they had been trading beaver and otter pelts to strangers, mostly to men from the British Hudson's Bay Company who gave them blankets and guns in return. The ship's chief, Captain John Dominis, told them to bring their furs to him instead, promising a higher price.

Throughout the winter and into the spring of 1830, the ship stayed and traded for pelts. But Dominis grew increasingly frustrated with the Indians. The furs they brought him were smaller than those they took to the British, he claimed. He called them together and held up a vial that appeared to be empty. Inside it was sickness, he told them, threatening to release it among them if they didn't bring him the best of the beaver.

Dominis may have learned this approach from an incident twenty years earlier. In 1811, having heard that Indians had massacred the crew of one of his company's ships, American pelt trader Duncan McDougall tried to prevent a similar slaughter at tiny Fort Astoria. He called the surrounding Indians together and held up a bottle, threatening to release the "skin sick" in it if they tried to harm his people.

McDougall's trick worked for him, but whatever success it brought Dominis, he wasn't satisfied. In July he abandoned his Columbia fur trading efforts and sailed up the coast.

Although Dominis took the sick Mr. Jones and his vial with him, he left behind exactly what he had threatened—a disease the Indians came to call "cold sick" (probably malaria) that destroyed their way of life.

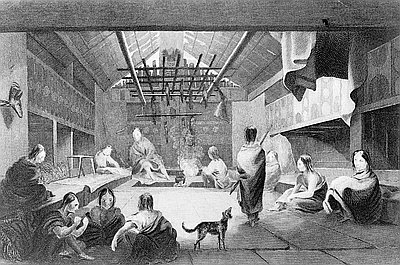

Less than twenty years before Dominis and his crew spent their year on the Columbia, a trader named Robert Stuart described a Chinook village he visited near the river's mouth as comparable in life and activity to American settlements back east. Only months after Dominis's visit, when David Douglass passed through the same area, he saw something much different.

"Villages, which had afforded from one to two hundred effective warriors, are totally gone," he wrote. "Not a soul remains. The houses are empty and flocks of famished dogs are howling about, while the dead bodies lie strewn in every direction on the sands of the river."

Other visitors at the time wrote of birds grown fat from gorging on corpses and villages burned to destroy the disease, leaving nothing behind.

The disease raged intermittently for the next three years, ultimately killing nine out of every ten people among the Lower Columbia tribes.

No one knows for sure if the "cold sick" came from Mr. Jones. The Indians claimed it came from contact with evil spirits in markers the Owyhee crew placed in the river channel. Whatever its origin, it was the deadliest of many diseases white traders and settlers brought, including smallpox, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, and dysentery.

These diseases took a horrifying toll because, unlike whites, the Indians had no established resistance or medicines, such as quinine, to treat them. The tribes were what epidemiologists (people who track the course of disease over time) call "virgin soil." They had other maladies — eye and liver ailments, for example — but their numbers had always been too small to nurture the greatest killers, which need large populations to thrive.

The Indians had cures of their own that had worked in the past for other diseases, primarily the heating of bodies in sweat lodges followed by cooling in nearby streams. By all accounts, these "cures" only weakened the "cold sick" victims further, causing them to die within hours.

Long after the "cold sick" subsided, the legacy of Mr. Jones and his captain, Dominis, lived on in the white domination of the Lower Columbia area and in a number of Indian myths, including a wishful one in which Coyote, the Indian trickster and hero, confronts and bests Disease.

The name of the Americans' ship, Owyhee, an eighteenth century name for Hawaii, can still be found on Oregon maps as the name of a river—a twenty-first century reminder of a massacre without guns.

© Michael McGregor, 2003

Michael McGregor is Associate Professor of Non-fiction writing and English at Portland State University.