- Catalog No. —

- G4294.A8A5 1846 .O82

- Date —

- 1913

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Geography and Places

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Research Library

- Regions —

- Columbia River Northwest Oregon Country

- Author —

- John Burr Osborn

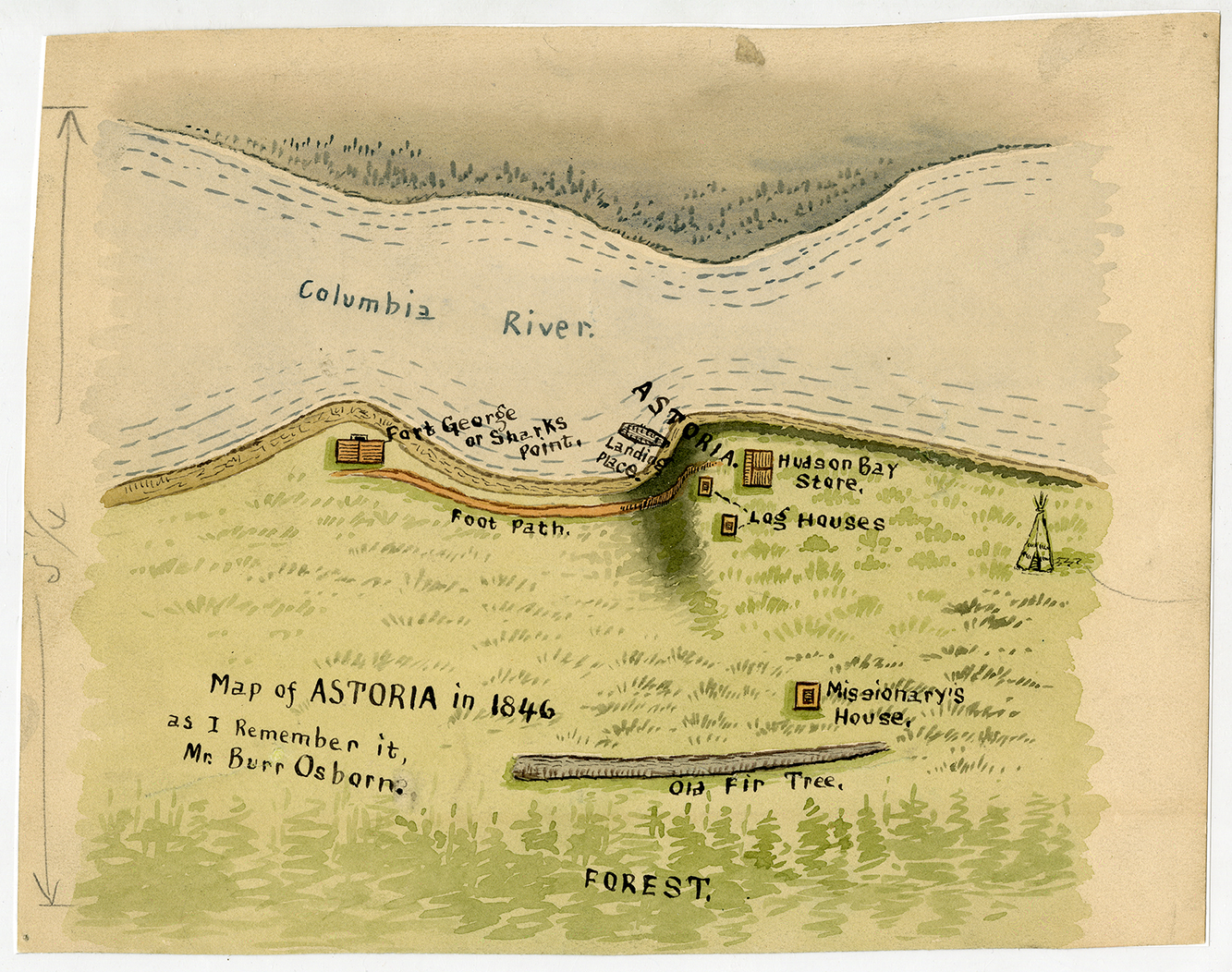

"Map of Astoria in 1846, as I remember it."

The maker of this map, John Burr Osborn, survived the 1846 wreck of the U.S.S. Shark, a U.S. Navy schooner, in the dangerous waters of the Columbia River Bar. The ship was lost, but the crew survived and spent many months in Oregon Country. His drew this watercolored map from memory in 1913. Osborn exchanged several letters in that year with the Oregon HIstorical Society's curator, George Himes, and Judge J. Q. A. Bowlby, who lived in Astoria. Osborn wished to know if any of the buildings and landmarks he remembered from 1846 were still standing. In the course of their correspondence, Osborn provided his account of the wreck, the salvage, and the time he spent onshore, including many details about the lower Columbia River landscape and people.

The Shark was commissioned to suppress the international importation of slaves to the United States (which Congress made illegal in 1807) and to protect American commerce from piracy. During the U.S. negotation with Great Britain over the occupation of Oregon Country, the Shark sailed to the lower Columbia River in August 1846 to "offset a British man-o'-war," but the matter had been settled by Congress by the time the schooner arrivedr, and Britain had conceded Oregon Country south of what is now the Canadian border to the United States with the Oregon Treaty. There was nothing for the crew to accomplish, then, but to observe and report. As they attempted to leave the Columbia in September, the Shark was pushed back by the wind and the powerful currents that characterize the Columbia River Bar (where the Columbia River empties into the Pacific Ocean). The ship careened into Clatsop Spit and sank. The crew made it to the south side of the river, coming to shore at the remains of another victim of the Bar--the U.S.S. Peacock, which wrecked in 1841.

Osborne remembered the handful of buildings at what is now Astoria as Fort George, the name given to the once-American Fort Astoria by the British Hudson's Bay Company, which controlled much of the fur trade in Oregon Country. Following the Oregon Treaty and the retreat by the HBC to Vancouver Island, Fort George became Astoria once more. By 1846, most of the HBC's business was conducted upstream at Fort Vancouver, and Osborne describes how unpopulated the settlement was by non-Natives.

"On arriving at Astoria, we found the village situated on a bluff, as near as I can remember about twenty or thirty feet high, and consisted of three log houses and one frame house. The log houses belonged to the Hudson's Bay Company....There were not many whites there, only what were in the employ of the company. One of the log houses in Astoria was a double one, used by the company as a branch store house and was kept by one man....he recieved the furs from the trappers and paid for them in dicker, such as guns, ammunition, beads for the Indians, whiskey, etc. The other two smaller log houses were for the use of the trappers....

These three log houses were situated within a few rods of the bluff and within a few rods of the landing, the landing being close to the beginning of the bluff.....there soon commenced an incline toward what they called Ft. George, where us boys built the log house and named it Sharkville, after our lost ship....The man that kept the store and the missionary were the only white men that I saw there."

The lower Columbia was home to thousands of Native people, who lived in villages along both sides of the river and its tributaries. The HBC created trading and labor relationships with village leaders, including the very powerful Chief Concomly. The Shark crew, by Osborn's account, had very little interaction with Indians, although they would have seen them navigating the river and dealing with the HBC.

If you overlaid a modern map of Astoria over Osborn's watercolor, you would see that his memory of the shape of Astoria's shoreline is not far off. Astorians have flattened the incline by building on timber pilings with access to the waterfront, but much of the town still sits on a steep incline to the bluff Osbron described. Fort George (the Fort George Brewery now sits on that site), is a little to the east where Osborne remembers, but he would likely find the view of the river, the bluff, and the dreaded Clatsop Spit familiar to him.

His map, and his account of his short stay in Astoria, provide important information about an interesting time in Oregon history. The year 1846 marks the tranisition from a fur trade dominated by Great Britain, the isolation of white settlements, and a time when Native people still controlled much of their trade alliances and hierarchies, to a period of intense American colonization and the near annihilation of Native lifeways and economies.

Written by A.E.Platt, 2022

Himes, George. "Letters by Burr Osborn, Survivor of the Howison Expedition to Oregon, 1846." Oregon Historical Quarterly 14.4 (December 1913): 355-365.

Related Historical Records

-

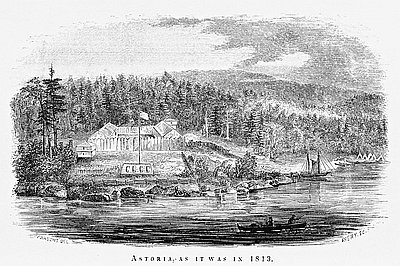

Fort Astoria, 1813

This lithograph is a reproduction of a drawing by Gabriel Franchère, published in his Journal of a Voyage on the North West Coast of America During the Years …

-

The Astorians and the Hudson’s Bay Company

The Astorians were the first fur traders to arrive. New York entrepreneur John Jacob Astor sent two groups of clerks to the Columbia River country—one by sea and …

-

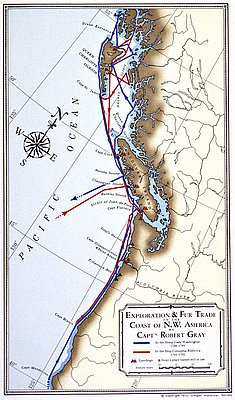

Exploration & Fur Trade by Robert Gray

The Oregon Historical Society produced this map in 1972 to illustrate the voyages of Captain Robert Gray to the Northwest Coast in the late eighteenth century. Captain Robert …