- Catalog No. —

- SB 112-59

- Date —

- c. 1866

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Unknown

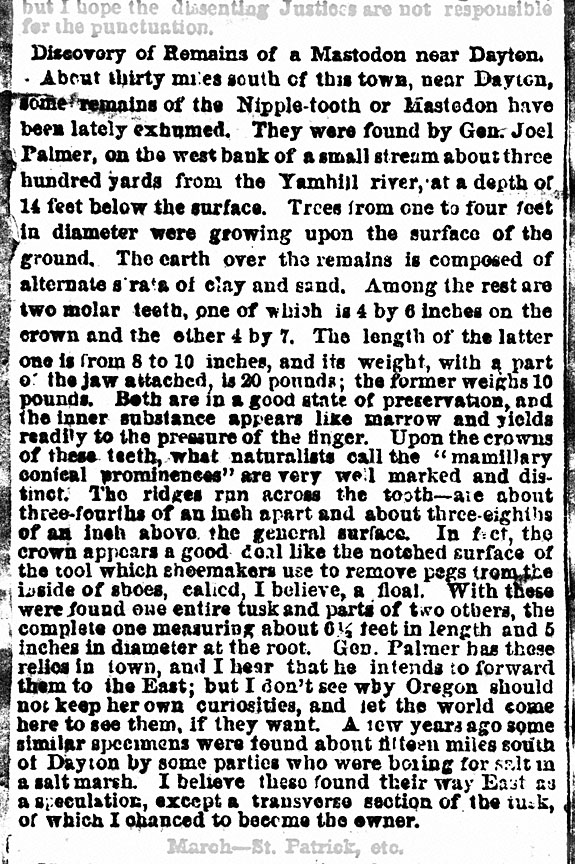

Discovery of Mastodon Remains near Dayton

This newspaper article describes the discovery of mastodon remains near Dayton by Joel Palmer(1810-1881), an influential Oregon pioneer. The article comes from an undated scrapbook, but it was probably written around 1866.

Mastodons were one of several species of proboscideans—the order of animals to which modern elephants belong—that once inhabited Oregon. Like their relative the wooly mammoth, mastodons were covered in hair, but they tended to be smaller and had narrower tusks than their better known cousins.Proboscideans went extinct in Oregon and elsewhere in North America between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago. Scientists disagree about the cause of these extinctions. Some believe that Native peoples overhunted proboscideans and other large fauna, while others believe climate change or possibly disease are better explanations for the disappearance of dozens of animal species at the end of the last Ice Age.

Euro Americans first discovered mastodon remains in 1705, when a large tooth and bone fragments were found in New York’s Hudson River Valley. At first it was thought the massive bones were those of giant humans killed in the great flood described in the Bible, but by the 1760s French scientists established that the remains were those of an ancient proboscidean.

Thomas Jefferson, who had a keen interest in North American fauna, believed that living mastodons and mammoths might still be present in the western reaches of the continent. In 1803, he instructed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to search for animals “which may be deemed rare or extinct.” Four years later, Jefferson personally financed an expedition—led by the recently returned William Clark—to excavate mastodon and mammoth fossils from Kentucky’s Big Bone Lick site.

One of the first recorded discoveries of proboscidean remains in Oregon was in 1858 or 1859, when a settler found a mastodon tusk in Polk County. An 1864 Oregonian article stated that “it was a genuine fragment of the Mastodon Giganteus—the old King of the North American Plains. The owner was offered $1,000 for it, but refused the money, and it was subsequently taken to New Orleans via. the Isthmus of Panama, thence to St. Louis, and finally to Rochester, New York, were it has just been added to the Cabinet of the Rochester University.” Mastodon teeth, bones, and tusks have subsequently been found throughout the state. They are particularly abundant in the John Day Valley, the Willamette Valley, and Lake County’s Fossil Lake area.

Further Reading:

Bishop, Ellen Morris. In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Oreg., 2003.

Orr, Elizabeth L., and William N. Orr. Oregon Fossils. Dubuque, Iowa, 1999.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.