- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 104953-104960

- Date —

- May 2, 1969

- Era —

- 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Exploration and Explorers, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Coast Columbia River Northeast

- Author —

- Lewis & Clark Journals. Thwaites. 1906. V6: 113-120

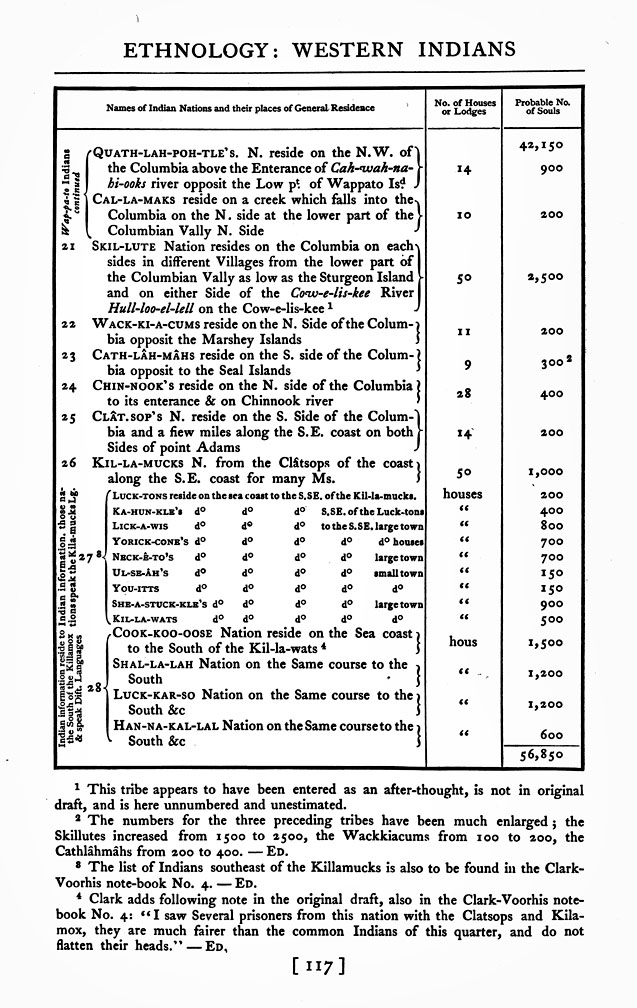

Estimate of Western Indians, Lewis and Clark Journals

Charged by Pres. Thomas Jefferson with recording the names of Native communities and estimating the size of their populations, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark took note of the number of inhabitants in each Native settlement they passed on their journey to the Pacific Ocean. They compiled that information during their long stay at Fort Clatsop, in the winter of 1805–1806, into what scholars call the Codex I (manuscript fragments attached to the journals) version of the Estimate of Western Indians. That version was later modified and published in the Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Journals, 1804–1806, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites and published by Dodd, Mead & Company in 1904–1905. (For information about the publication history of the journals, see Gary Moulton’s introduction to volume 2 of The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.)

No one knows exactly how many people lived on the lower Columbia River in 1805–1806. The closest we can come is the figures that appear in Codex I and Thwaites’s published edition of the journals. The Codex I version and the published version, however, differ significantly in their estimates of the Native population west of the Rocky Mountains. In the Codex I version, for example, Lewis and Clark estimate that 9,140 people lived along the Columbia River from Celilo Falls downriver to the Pacific, including the large villages on Sauvie Island. In Thwaites’s published version, which is reproduced here, the number given for the same area is 14,890.

Anthropologists Robert Boyd and Yvonne Hajda examined the two versions and write that the Codex I estimate represents the winter population and the published version represents the spring population. While the Columbia River region was rich in natural resources, those resources were not present in all places at all times. Edible plants and game animals were available at certain times of the year, and people adjusted their seasonal schedule accordingly, following the resources as they became available. When the Corps of Discovery traveled up the Columbia in April 1806, for example, river villages would have been swelled by inland visitors taking advantage of the spring salmon runs. This seasonal movement, Boyd and Hajda write, explains the different numbers found in the two versions of the estimate.

Written by Cain Allen, 2004; revised 2021

Further Reading:

Boyd, Robert T., and Yvonne P. Hajda. “Seasonal Population Movement along the Lower Columbia River: The Social and Ecological Context.” American Ethnologist 14, no. 2 (1987): 309–326. (This article, available on JSTOR, contain tables and maps valuable for teachers and students.)

Lewis, Meriwether, and William Clark. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Vol. 2, edited by Gary E. Moulton. Bison Books edition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.