- Catalog No. —

- OHS Press Map 1983

- Date —

- 1983

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration), 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform), 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II), 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Government, Law, and Politics, Native Americans, Oregon Trail and Resettlement

- Credits —

- The Press of the Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Central

- Author —

- Jeff Zucker, Kay Hummel, Bob Hogfass

McQuinn Strip Land Dispute

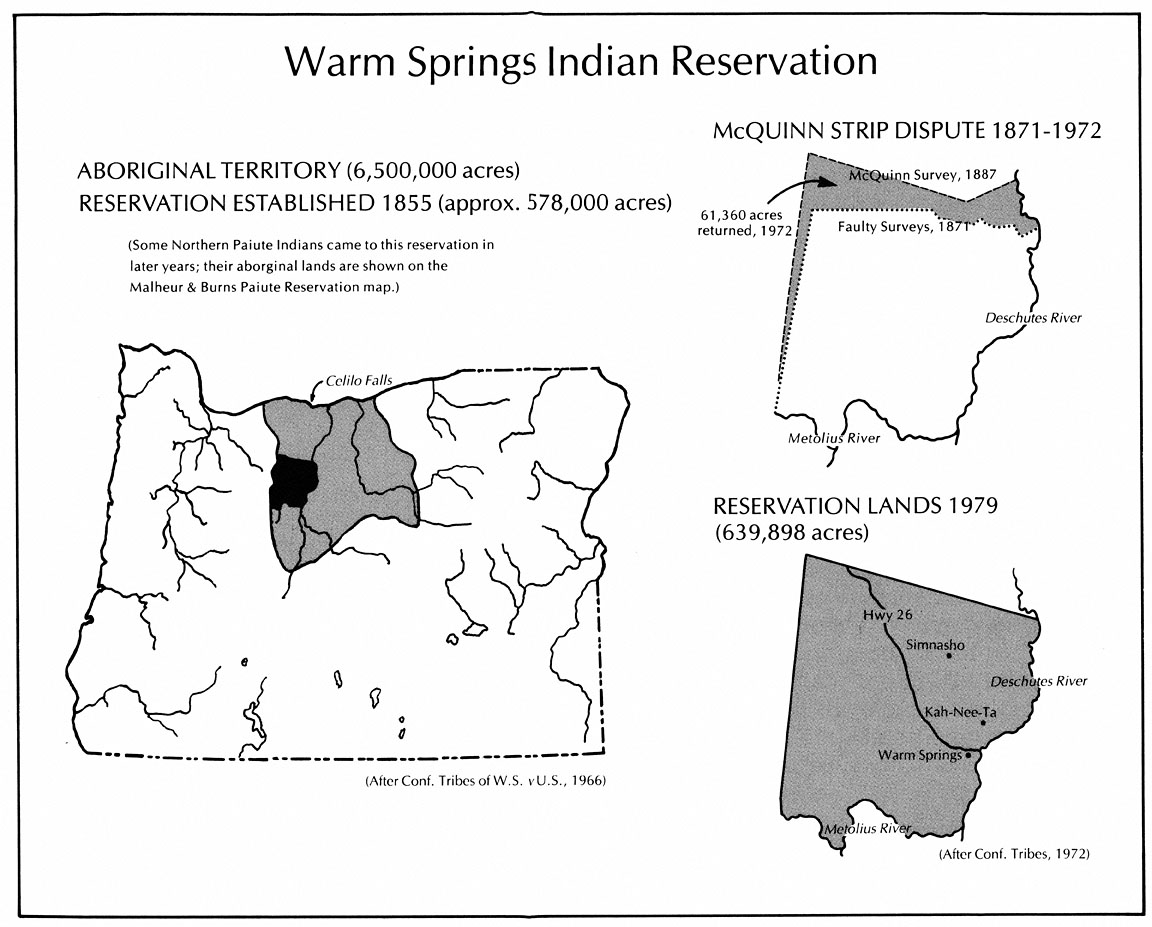

In 1855 the “Indian tribes of Middle Oregon” ceded ten million acres of their ancestral lands to the United States, reserving approximately 600,000 acres for their sole ownership and use. According to the language of the treaty, the northeastern corner of the reservation was to be “in the middle of the channel of the De Chutes River opposite the eastern termination of a range of high lands usually known as the Mutton Mountains.” When Tom B. Handley and R.T. Campbell carried out the reservation’s first boundary survey in 1871, they misidentified the Mutton Mountains and began their survey from a mountain ridge farther south resulting in a reservation much smaller than the tribes had expected and prompting an immediate protest.

Congress responded to the tribes’ complaints in 1886 authorizing a second survey. The following year, John A. McQuinn began his survey using the Mutton Mountains known to the Indians as his landmark and subsequently ended up with a reservation over 80,000 acres larger than the first survey. Non-Indians who had settled in what became known as the McQuinn Strip, voiced their protests to Congress over any changes to the first survey. Congress commissioned a study of the dispute in 1890 and four years later decided in favor of the non-Indian settlers, making the Handley-Campbell boundary line official.

The Warm Springs tribes continued their protests. In 1917, Congress commissioned another study which confirmed the validity of the McQuinn survey. Unwilling to transfer disputed land, the federal government offered the tribes money to compensate them for their loss. The tribes rejected the offer. In 1930, Congress passed legislation allowing the tribes to take the land dispute before the U.S. Court of Claims. Eleven years later, in Warm Springs v. United States, the court recognized that minus an 8,000-acre triangular plot in the northeastern corner, the McQuinn line was legitimate. Unfortunately for the tribes, the court still refused to transfer ownership of the McQuinn Strip and offered only financial compensation for their loss. In 1945, the Court of Claims determined that the United States owed the Warm Springs tribes $241,084. The same court concluded that since the U.S. government had already spent $252,089 “in behalf of the tribes,” dating back to 1855, that no money was owed to the tribes and the use of “offset” costs actually meant that the Warm Springs tribes owed the government $11,005. The case was dismissed.

Congress passed legislation in 1948 awarding the tribes all of the net revenues earned from timber sales and grazing permits on the McQuinn Strip, amounting to a cumulative total of $5,951,386 by 1970. Still, the tribes continued to press for the return of the land. Their persistence paid off in 1972 when Congress passed Public Law 92-427, placing 61,360 acres of public land from the Mount Hood and Willamette national forests back into the tribes’ possession. The 8,000-acre land claim in the northeast corner that was invalidated by the courts in 1941, 1,000 acres which had become part of the Mt. Jefferson Wilderness Area, and 17,251 acres of privately owned land were left outside of tribal ownership.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2002.

Map reprinted with permission: Zucker, Jeff, Kay Hummel, Bob Hogfoss. Oregon Indians: Culture, History, and Current Affairs: an Atlas and Introduction. Portland, Ore.: 1983. © 1983 Western Imprints, the Press of the Oregon Historical Society.