- Catalog No. —

- Mss 1383

- Date —

- 1858

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Agriculture and Ranching, Oregon Trail and Resettlement, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality, Religion

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Willamette Basin

- Author —

- Theodore M. Swett

New Odessa Colony

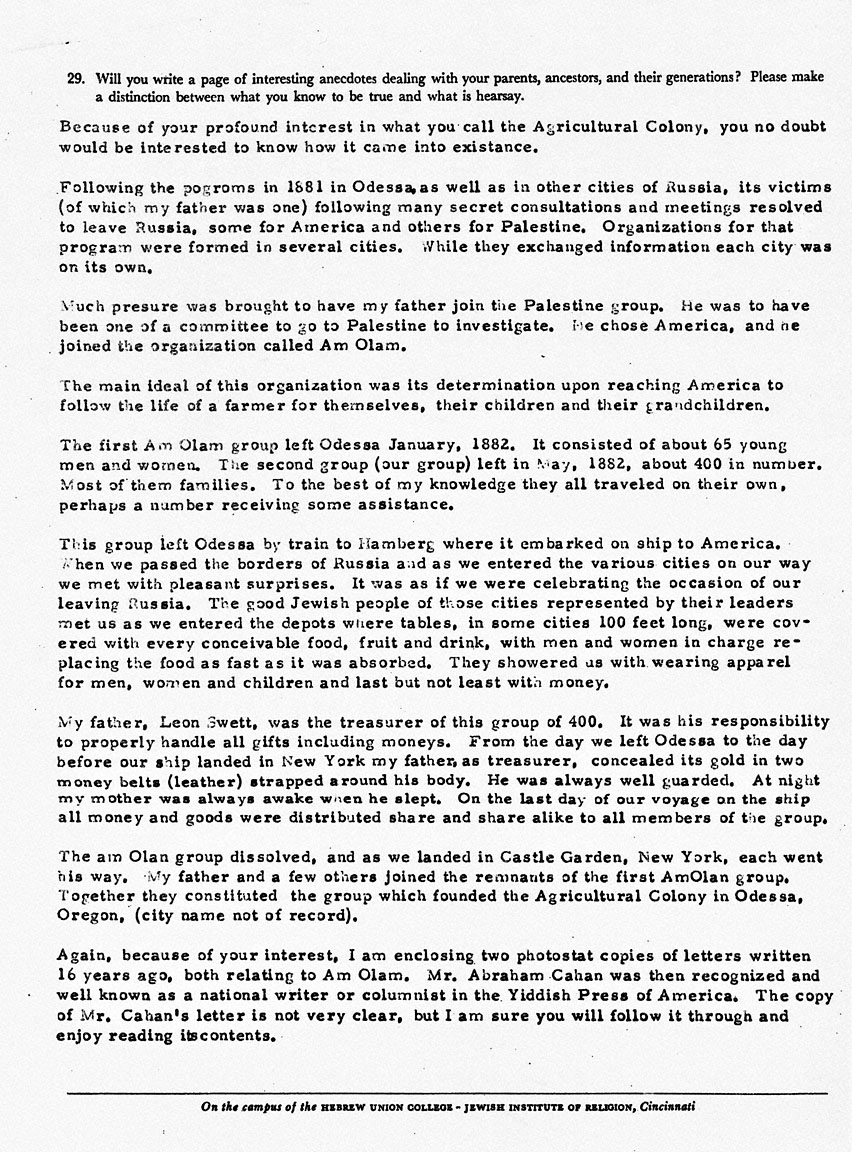

In 1958, Theodore M. Swett answered a questionnaire from the Jewish Institute of Religion at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. In one portion, Swett detailed his knowledge of New Odessa, a short-lived Jewish agricultural colony located near present-day Glendale, Oregon. Swett was a child at the time of the colony’s existence, and his recollection of its history is one of the few surviving first-person accounts. Although the Swett family moved west with the first wave of New Odessa’s colonists, they withdrew their membership on reaching Portland and took up a homestead claim in Washington County.

In 1881, the assassination of Czar Alexander II led to a renewed wave of pogroms against Jewish communities across the Russian Empire. Many Jews responded to the rise in anti-Semitic violence by emigrating. In the Ukraine, one of the emigration organizations formed to assist refugees was called Am Olam (“the eternal people”), which encouraged Jews to resettle in Palestine and in the United States as agriculturalists. Am Olam’s leaders urged Jews should abandon their business-oriented lifestyles, which they believed provided a basis for degrading Jewish stereotypes and conspiracy theories, and return to the age-old agricultural traditions documented in the Torah.

The first group of “Am Olamniks” arrived in New York in January 1882 and made plans to form a socialist agricultural commune. They sent scouting parties to Texas, Oregon, and Washington before deciding to locate their community in Oregon’s Douglas County. In September 1882, thirty-four Am Olamniks arrived in Portland, and after negotiating the purchase of 760 acres from Hyman and Julia Wollenberg in March 1883, many relocated to the heavily-wooded land between Wolf and Cow creeks in the upper Umpqua River Valley. According to the Articles of Incorporation for New Odessa, the community was created for “mutual assistance in perfecting and development of physical, mental, and moral capacities of its members.”

By 1884, the population of New Odessa had grown to sixty-five but the community was marked by a disproportionately high number of single men compared to a small number of families and single women. For its income, the community cut and sold timber to the Oregon and California Railroad for use as railroad ties and fuel. For food they planted vegetables and wheat on more than 100 acres of land and hunted and foraged food from their surrounding environment. Where the colonists found themselves short on agricultural experience and supplies, the surrounding community lent tools and expertise to help them.

Political divisions within New Odessa ultimately led to the community’s demise. William Frey, a charismatic, but uncompromising Russian atheist who had been asked to join the community in 1882, believed that the entire community should adhere to a “religion of humanity” with philosophical roots in the positivism preached by Auguste Comte. Not everyone was willing to adhere to Frey’s communal ideology, and by 1885 the community had fractured beyond repair. During the next two years, the population of New Odessa abandoned the community, most returned to New York, and in 1888 the land was returned to its previous owners.

Further Reading:

Rosenthal, Herman. “Chronicles of the Communist Settlement Known by the Name ‘New Odessa,’” trans. Gary P. Zola. In American Jewish Farmer. Cincinatti, Ohio, 1986.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.