- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 26558

- Date —

- 1881

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Arts, Environment and Natural Resources, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Courtesy of Pacific University Archives

- Regions —

- Willamette Basin

- Author —

- I. G. Davidson

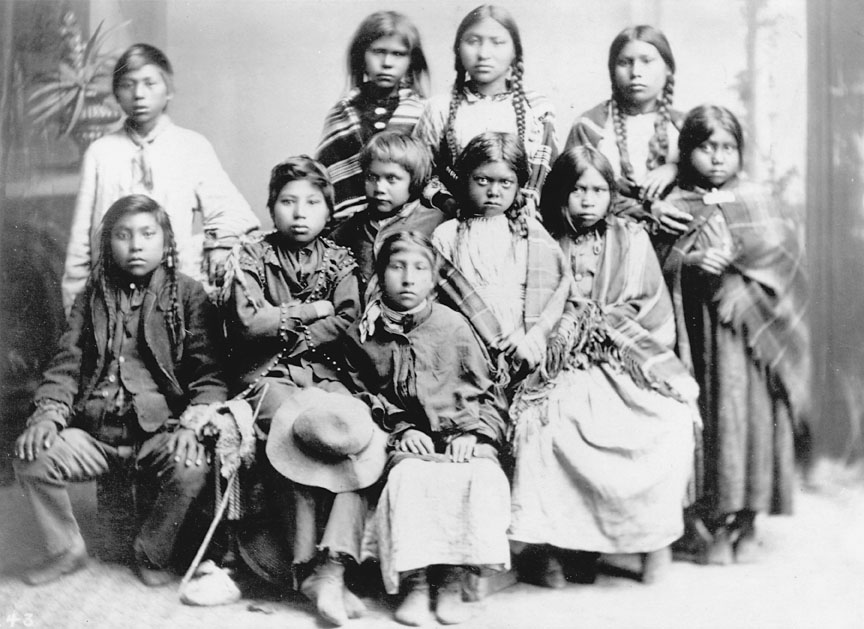

New Recruits, Forest Grove Indian School, 1881

This group of children from the Spokane tribe was recruited to attend the Forest Grove Indian and Industrial Training School in 1881 as part of the effort to assimilate Native Americans into the dominant U.S. culture. The collapse of Indian resistance to white encroachment in the late 1870s signaled a shift in U.S. Indian policy from one of separation that had founded the reservation system to one of assimilation. According to the reformist view, reservation life did little to prepare Native Americans for integration into white society. In response to this failure, reformers undertook a policy that would use off-reservation boarding schools to prepare Native American children for eventual assimilation.

In 1879, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz, approved the formation of the first two off-reservation boarding schools. One, the Carlisle Indian School was located in Pennsylvania and was headed by Richard Henry Pratt, a former military officer whose previous experiment with Indian education at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia had been viewed as a success. The second school, the Forest Grove Indian and Industrial Training School was established on the grounds of Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon in 1880 by Melville C. Wilkinson, a former U.S. Army captain. Wilkinson, a passionate assimilationist, structured the Forest Grove School program along the lines of the Carlisle model used by his friend, Richard Pratt.

The assimilationist program at the Forest Grove Indian School—like those at other off-reservation schools—attempted to erase all vestiges of the students’ Indian identity through isolation from native culture and through teaching the necessary skills to become “civilized.” In addition to academic training, male students were given vocational training in carpentry, shoemaking, and farming, while female students received training in the domestic arts of sewing, cleaning, and cooking. In the process, the school benefited from the children’s labors. Students performed much of the maintenance around the school and it was not unusual to hire out them as laborers. Any financial gain from the student labor went directly to the school, which struggled constantly with a shortage of government funding and charitable donations.

Financial difficulties prompted the Forest Grove School’s second superintendent, Henry J. Minthorn, to seek a new home. Unable to expand its agricultural operations, the school moved to the Salem area in 1885 where it was later renamed the Chemawa Indian School. The new school thrived in the Salem area, becoming one of the more successful boarding schools in the government system. The Chemawa Indian School, which still operates today, has abandoned the assimilationist roots of its programs, and instead, has become an institution which encourages Native American student to take pride in their heritage.

Further Reading:

Reddick, Susan M. and Cary C. Collins. “Forest Grove and Chemawa Indian School: The First Off-Reservation Boarding School in the West.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 101, 2000: 442-507.

Fritz, Henry Eugene. The Movement for Indian Assimilation, 1860-1890. Philadelphia, Pa. 1963.

Hoxie, Frederick E. A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920. Lincoln, Nebr., 1984.

Archuleta, Margaret L., Brenda J. Child and K. Tsianina Lomawaima. Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences, 1879-2000. Phoenix, Ariz., 2000.

Written by Dane Bevan, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.