- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 57563

- Date —

- 1923

- Era —

- None

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Coast

- Author —

- Unknown

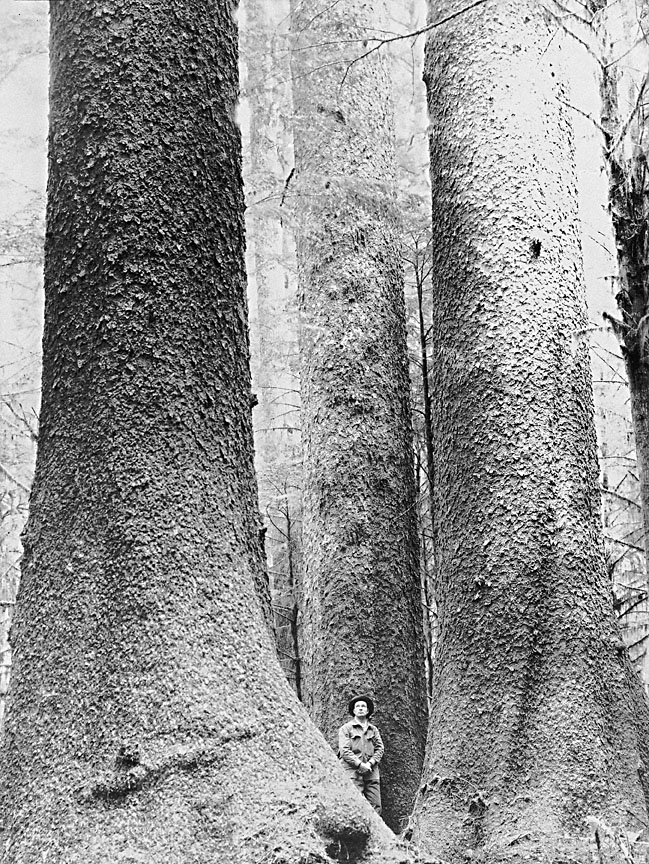

Old-Growth Sitka Spruce, 1923

This photograph was taken in August 1923. It shows a man standing in a stand of old-growth Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) located in what is identified on the back of the photograph as the Manary Logging Company’s Blodgett tract in Lincoln County.

The vegetation of the Oregon Coast Range can be divided into several distinct types. The coastal fog belt is dominated by Sitka spruce like those shown above. Sitka spruce range from northern California to southeastern Alaska. Unlike many other conifers in the region, Sitka spruce need abundant moisture in the summer, so they only grow in the coastal fog belt and in the valley bottoms of major coastal rivers. Douglas fir tends to be the dominant tree species east of the Sitka spruce zone. Oak savannah and prairie were also important vegetation types on the eastern slope of the Coast Range prior to white settlement.

Although the historical distribution of vegetation types in Oregon’s Coast Range prior to white settlement is fairly well known, scholars, land managers, and activists disagree about the original extent of old-growth forests like the one shown in the photograph above. A number of researchers have estimated that old-growth forests—often defined as stands 175 years old or older—covered approximately 50 percent of western Oregon and western Washington in the early nineteenth century, though some estimates range considerably higher.

Some researchers, however, have argued that old-growth was relatively rare in Oregon’s Coast Range prior to white settlement. Forest historian Bob Zybach, for example, argues that instead of a “blanket of old-growth” at the beginning of white settlement, the forests of the Coast Range consisted primarily of a mosaic of young to mid-age Douglas fir, with only scattering old growth. He argues that widespread landscape burning by Native peoples was responsible for this relative lack of old-growth.

Not all scholars agree that Indian landscape burning was the driving force behind forest dynamics in Oregon’s Coast Range. Forest ecologist James Agee, for example, argues that the “case for widespread aboriginal fires throughout the Douglas-fir region is not convincing.” Citing a lack of evidence that Native peoples were responsible for upland fires, Agee argues that lightning was likely the primary ignition source in westside forests prior to white settlement.

Such debates about the history of forest dynamics in Oregon’s Coast Range have important implications for modern forest management practices, particularly the conservation of old-growth-dependent species like the marbled murrelet and the northern spotted owl.

Further Reading:

Agee, James K. “Fire History of Douglas-Fir Forests in the Pacific Northwest.” In Wildlife & Vegetation of Unmanaged Douglas-Fir Forests. Edited by Leonard F. Ruggiero, Keith B. Aubry, Andrew B. Carey, and Mark H. Ruff. Portland, Oreg., 1991.

Wilderness Society. Ancient Forests of the Pacific Northwest. Washington, D.C., 1990.

Zybach, Bob. “The Great Fires: Indian Burning and Catastrophic Forest Fire Patterns of the Oregon Coast Range, 1491-1951.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Oregon State University, 2003.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006