- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 97024

- Date —

- c. 1940

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II)

- Themes —

- Women

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Unknown

Woman Irons in Electrified Kitchen, c. 1940

This photograph of E. H. Davis, from Eugene, Oregon, is also preserved in the National Archives, along with other photographs related to the efforts of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), a federal organization created as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The goal of the REA was to extend the benefits of electricity to the nation’s rural households.

The electrification of American homes began in the 1880s. However, since most homes weren’t outfitted with appropriate wiring and electrical outlets, early electrical use in homes was often limited to wiring for fixed lighting, usually in the walls or ceiling. Makers of electrical products took the first step toward making electricity more useful in the home in 1917, when six of the biggest manufacturers agreed to standardize their plugs and outlets. Subsequently, consumption of electrical appliances surged during the 1920s. By the end of the decade approximately 60 percent of all U.S. households owned an electric iron, 28 percent owned vacuum cleaners, and 20 percent owned washing machines. Other appliances, like refrigerators and ranges, were too high-priced for most household dwellers—renters who were more likely to take out loans for automobiles.

Although women’s magazines promoted electrification during the 1920s through “rational homes” and “better homes” campaigns, it wasn’t until in the midst of the Depression during the 1930s that the federal government began to encourage the modernization of homes with legislation like the National Recovery Act, which promoted the consumption of electrical goods, and the National Housing Act, which provided loans for Americans interested in buying and/or modernizing homes of their own. During World War II, the federal government continued to encourage the modernization of American homes through their subsidization of defense housing related to wartime industries. After the war ended, the postwar housing boom continued to increase the number of electrified homes in the United States.

Historians and sociologists agree that while electrical appliances were marketed and sold to housewives with the appeal that they might liberate women from their household labors, they in fact did not. While the new technology did reduce the drudgery involved in much of the daily labor of housework, the time spent housekeeping actually increased. Ironing and laundry got easier, but families bought more clothes and washed them more often. The removal of coal-fired ovens and heaters reduced the amount of soot to clean from the home, and refrigerators reduced the time spent preserving foods, but rising expectations in culinary arts, home management, and child care more than made up for the time saved. The lives of housewives became imbued with the new science of home economics. Homemakers were expected to organize their families’ lives and living quarters according to the standards of technical experts writing for women’s magazines and local newspapers. Those women who failed to meet those standards not only ran the risk of being perceived as failed homemakers, but as being failed mothers and wives as well.

Further Reading:

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: 1983.

Ogden, Annegret S. The Great American Housewife: From Helpmate to Wage Earner, 1776–1986. Westport, Conn.: 1986.

Tobey, Ronald C. Technology as Freedom: The New Deal and the Electrical Modernization of the American Home. Berkeley: 1996.

Related Historical Records

-

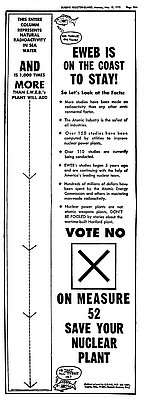

EWEB is on the Coast to Stay!

This political advertisement was paid for by Citizens for the Orderly Development of Electricity (CODE). It appeared in the Eugene Register-Guard on May 18, 1970, in opposition to …

-

Electrifying the City

Just as the railroad network expanded the scale of Portland’s economy, new technologies for moving people around the city, spanning rivers, and erecting multistory buildings expanded the scale …