Southern Oregon

Many people in Douglas, Curry, Josephine, Jackson, and Klamath counties have joined with their northern California neighbors into the mythical State of Jefferson. Named for the U.S. president who sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark west in 1804-1806, this part of Oregon sees itself as self-reliant and sometimes neglected by the state’s power centers. The region’s independent spirit lives in the stories of pioneer heritage so celebrated by residents in material and verbal arts, and at festivals. While southern Oregonians still claim pioneer resourcefulness, they also welcome new versions of history and culture. Native Americans, Latinos, and others whose folklife was previously hidden now vie for a place in representing this region. The range of stories is as varied as the area’s complex ecosystems: oral histories told by pioneer descendants; the collected stories of Klamath, Modoc, and Coquille elders; deeply embedded Mexican legends; and the experiences of women.

In 1846, a group led by Jesse Applegate sought a southern route west that would avoid the hazards of the Columbia River and the Oregon Trail. The Applegate Trail, also known as the South Emigrant Road, traversed the Rogue River Valley and opened up the region to whites. In 1850, the Donation Land Act granted land to settlers, 320 acres to each man, twice that for married men. The first confrontations between Native Americans and westward settlers were more strained and often bloodier in southern Oregon than in other parts of the state until well into the 1850s mining craze. Twilo Scofield and Tom Nash report that of 242 emigrants killed during the pioneer movement west, 108 died in southern Oregon. Whites called the Native groups—including Takelma, Tututni, and Shasta— Rogue Indians, reflecting their feelings about indigenous people. The Rogues fought back against the incursions, and in the late 1850s, the Indians were forced onto a coastal reservation. Place names such as Grave Creek, Bloody Run, and Dead Indian Road carry the legacy of the violent clashes.

The twentieth century brought another sort of decimation. Federal economic and educational policies sought to assimilate Native American people into mainstream culture, often nearly destroying Native cultural life. These practices culminated in the 1950s termination period, when many tribes lost their treaty rights and their status as sovereign nations. Even before the Klamath and Coquille tribes suffered this economic and political blow, their children had been sent to English-only boarding schools, beginning the process of cultural dismantling. While the government thwarted the transmission of traditional Native culture, some forms of oral tradition and folk arts survived. Such resilience helped keep alive each group’s cultural life until the tribes regained federal recognition in the 1980s. Among the Coquille, stories of Tallapus or Old Man Coyote reemerged, and the Klamath began language programs. At the end of one of the first classes in 1989, one participant described her deep satisfaction at being able to tell her husband in Klamath that she loved him.

The Klamath’s thriving cultural life testifies to tenacity and adaptability. Master artist Priscilla Bettles, who learned to make cradleboards from her mother, is an important example. In the 1990s, she taught her granddaughter and apprentice artist Priscilla Witcraft to fashion her first cradleboard. Women used the boards to carry their babies as they went about daily chores, a striking marriage of beauty and utility. Bettles said: “Designs I put on cradleboards and other things that I make are the Indian way of searching for beauty and having it around you.” Bettles also taught moccasin making, while her son Quinten led the Bear Guts singing and dancing group.

Agnes Pilgrim, of the Rogue River Indians now living in Grants Pass, was the oldest remaining member of the Takelmas in the early 2000s. She spent her life advocating for indigenous people and speaking for other people and the natural world. “The tree people can’t speak, and the deer can’t answer the phone. The animal kingdom can’t run a computer…. I want to be a voice for the voiceless.” Before her husband Grant died, they worked together to revitalize and teach a number of traditional practices, including cedar bark basketry and beadwork. They also resuscitated the sacred salmon ceremony with funds solicited from tribal casinos. The revival of this ceremony reveals how tenuous cultural life can be. Without the Pilgrims’ tenacity and economic assistance, the Takelma’s salmon ceremony might not have survived.

While varied groups live peacefully in southern Oregon today, economic and symbolic clashes can occur. In 2001, water wars erupted between farmers and the Klamath Tribes when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation diverted irrigation water to protect endangered sucker fish. Place-names, a central feature of folklife, bring values and interpretations of history to the fore. Geographic monikers for white settlers displaced indigenous names and derogatory names also linger. In 2001, the Oregon legislature passed a law “urging state and federal officials to remove the term squaw from place names in Oregon.” As of 2005, 140 “squaw” names still remain.

The idea of pioneer resourcefulness is continually evoked and revived in folk arts, such as rag rugs and among members of the quilting groups that proliferate through southern Oregon. The influence of occupational patterns that began with earliest settlement also lives on in folk arts forms. Logging, long central to the heavily forested Cascades and Calapooia Mountains, is no longer a mainstay of the economy, but its legacy continues in hand-carved furniture and chain saw sculptures.

A pioneer character that fills southern Oregon’s verbal lore is Hathaway Jones, a teller of tall tales who traversed the Rogue River Valley in the late nineteenth century as a mule-team mail carrier. Historian Stephen Dow Beckham has pointed out how firmly rooted this raconteur remains in the mountain wilderness surrounding the Rogue River. Many tales boast of Hathaway’s prowess in hunting, his cleverness, and wit; others celebrate the prodigious strength and courage of his father and grandfather. Some stories are original; others retell tales that circulated in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century America. The stories’ persistence reveals how Jones’s independence and wit remain symbolic resources in the so-called State of Jefferson. This identity feeds a larger sense among Oregonians of being independent thinkers and actors on the national stage. Folklife can be linked to contemporary issues from land-use policies to legislation on assisted suicide.

The tiny community of Malin in Klamath County sits on the state line with California and translates as “wonderful country” in the language of the original Czech settlers who arrived in 1909 by way of Chicago, drawn by the promise of arable land. Their first years were harsh. Tom Nash and Twilo Scofield report that the settlers’ potato crops would not have survived the windstorms, floods, and plagues of pests but for the aid of local ranchers. Today, Czech heritage is celebrated in story, ritual, and especially ethnic foodways. Poppy seed pastry, kolace, other forms of pastry, sauerkraut, homemade noodles, and sausage are all featured in annual festivals. Such events become increasingly important to small town economies as tourism flourished throughout Oregon.

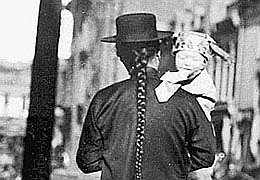

Another type of pioneering heritage in southern Oregon has been increasingly recognized. The thriving Latino community recalls the Hispanic presence that preceded Euro-American settlement. From 1542 into the nineteenth century, Spanish explorers mapped and claimed the coast, a heritage lingering in place-names like Cape Perpetua and Cape Blanco. In 1821, when Mexico declared independence from Spain, the northern Mexico border was near today’s Oregon-California line. After the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, the United States annexed the land south of the border. Mexicans continued to migrate north—drawn by the mining booms of the 1850s, the building of the railroads, and other economic opportunities. Nothing shaped Oregon’s Hispanic experience as profoundly as the creation of the Bracero Program, which brought farmworkers north during World War II to fill critical labor shortages. In 2010, Oregon’s population was 11.7 percent Hispanic with a projection of further growth during the first half of the twenty-first century.

Latino folk arts have been visible, vital, and growing in importance, reflecting the influences of mestizos of mixed heritage and many indigenous cultures: Mixtecos or Zapotecas from Oaxaca, Otomis from Hidalgo, Nahuas from Veracruz, and Purépechas from Michoacan. All speak different languages, and all have rich folk art traditions. Dagoberto Morales Duran of Michoacan descended from four generations of craftsmen. He learned straw weaving at age five, putting aside his work temporarily during college. When he moved to Oregon, he resumed weaving wheat into mats, baskets, fans, and objects for religious ceremonies and festivals. His woven Virgen de la Salud statues and other arts have reconnected him to his culture, created income, and helped educate others about Mexico.

Local festivals and county fairs also highlight Latino cultures. At Cinco de Mayo, which celebrates Mexico’s victory over the French, mariachi bands play and cooks make empanadas and tamales from corn ground on a metate, a flat stone base. Mexican charrería or cowboy traditions are often part of such festivals. Twenty-first-century charros are rooted in the working traditions of the West at rodeos. Young men cruise the streets at festival time lowriders, cars controlled by customized hydraulic systems that allow them to move side to side as well as up and down, and in brightly decorated cars, trucks, and SUVs.

Legends root international tradition to local form. La Llarona, the Legend of the Crying Woman, still flies from the tongues of elders to children in the United States and Mexico. Legends often begin with “Había una vez…” ‘There once was…’. Versions of La Llarona differ slightly, but all tell of a señora who drowns her children for the sake of a lover who then abandons her. La Llarona roams the river mourning and wailing for her lost children. Some say that the legend, which is still told in southern Oregon, keeps wandering children away from rivers. Others say that the tale upholds fidelity in marriage for traditional tellers, and younger women might use it to issue warnings about faithless men and the need for female independence. Texts are never neutral, and folklore can serve multiple purposes.

Some folk art forms would surely be lost without the intervention of individuals and institutions. The Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program of the Oregon Folklife Network at the University of Oregon encourages the preservation of traditional arts. Small stipends are granted to master artists to pass on their knowledge to someone from their cultural community. Hedy Connelly of Grants Pass received a grant in 1998–1999 to learn the Ukrainian tradition of egg dying called pysanky. Pysanky—from the Ukrainian pysat ‘to write’—displays patterns that include religious symbols as well as those from the natural world. Ukrainians give pysanky all year round to mark special events and stages of life; some people bury pysanky under the four corners of a new home for good luck. Hedy sought this tie to her past after having children of her own, calling an aunt in Wisconsin to learn about pysanky.

Sometimes, a new group enlivens a community in unexpected ways. many retired men and women have moved to southern Oregon, drawn by the temperate climate and excellent medical resources. Novel art forms reflect the status of many elders as pioneers in another sense, breaking ground in the experience of aging. Some artists learn new forms later in life after release from the demands of jobs or raising children; others perfect skills begun at an earlier age. Looming above Medford, the Rogue Valley Manor Retirement Center houses many such folk artists. In 1989, ninety-six-year-old Ernie Kimball was a model of adaptability as he learned to carve wildlife figures. The same year, the Oregon Folklife Program featured an exhibit called The Creative Continuum to highlight the work of elders. Their creativity challenges a dominant cultural story—that of aging as inevitable decline. While aging brings struggles with infirmity and loss, it also offers time for reflection and the perfection of craft.

Lest anyone think that folk arts are quaint, it is important to look to places like Ashland. Edging the California state line, this 1850s flourmill town hosts the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, with performances in the largest and oldest rotating repertory theater in the United States. According to folklorist Tom Nash, superstitions and legends abound in the theater. One must never say the name “Macbeth,” but rather refer to Shakespeare’s Macbeth as “the Scottish play.” Actors should keep shoes worn on opening night and never bring fresh flowers on stage.

Tales of rural and urban, arts of young and old, logger and tourist—all histories and art forms are local, part of larger narratives that enclose them like Russian nesting dolls. Sometimes vernacular forms break the enclosure, as when folk arts by elders challenge the dominant cultural narrative of decline or Native Americans relate the story of termination as colonial oppression. Local narratives interact with and sometimes change broader regional and national stories. Southern Oregon’s folk traditions encompass tales of Hathaway Jones, Ashland’s theater superstitions, the struggles of Indian people, and the intertwined worlds of Anglos and Latinos. All invite us to ponder how folk arts take shape in relation to—and sometimes tension with—one another, producing novel forms and new cultural stories.

© Joanne B. Mulcahy, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP Staff

Sections

Related Historical Records

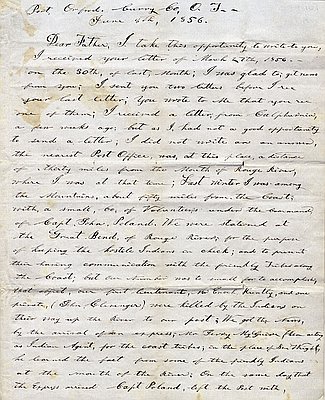

From Granville Arnold to his Father

The 1850s were easily the bloodiest decade in the history of southwestern Oregon. While relations between whites and Indians in the Rogue Valley had long been marked by …

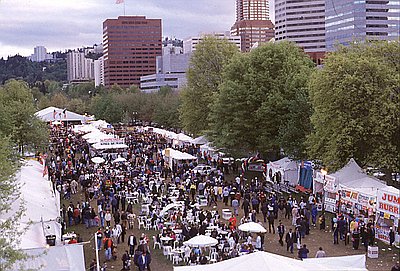

Cinco de Mayo Festival

Portland's Cinco de Mayo Fiesta is held annually at Portland's Tom McCall Waterfront Park and is organized by the Portland Guadalajara Sister City Association (PGSCA). The three-day Fiesta …

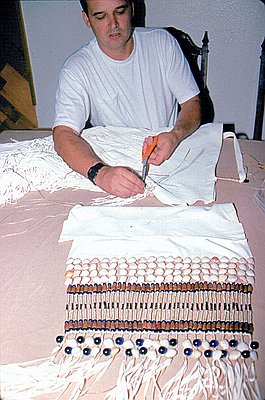

Tututni Shell Dress

This photograph of Alfred “Bud” Lane III busy at work cutting fringes from deer hide during the construction of a Tututni shell dress was taken by Nancy Nusz …