- Catalog No. —

- OHS Lib 971 H886 v.2

- Date —

- September 1, 1843

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement)

- Themes —

- Oregon Trail and Resettlement, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River Oregon Country

- Author —

- Adolph Etoline

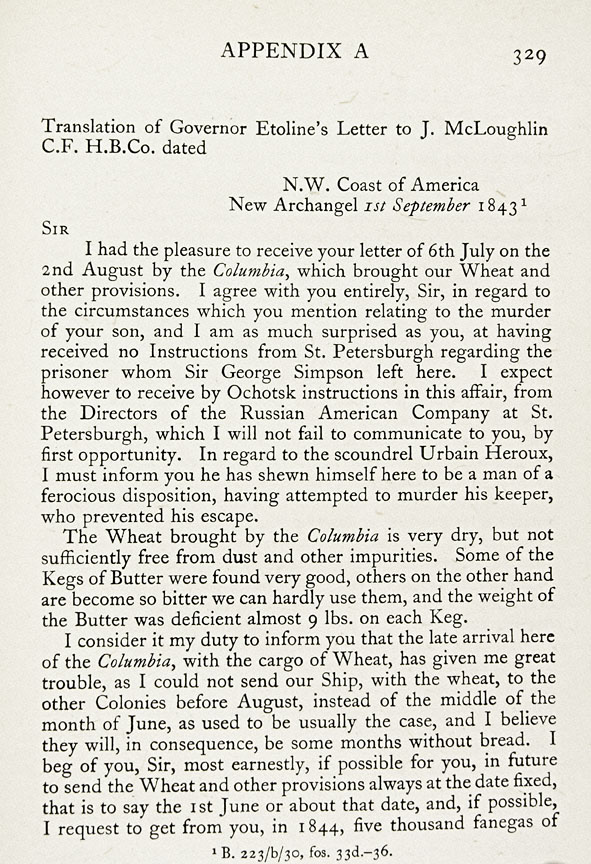

From Adolph Etoline to John McLoughlin, 1843

On September 1, 1843, Adolph Karlovich Etoline, governor of the Russian American Company (RAC), wrote this letter to John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) Columbia Department, most of which deals with operational arrangements between the two companies.

In February 1839, high-level negotiations between the HBC and RAC produced a ten-year contractual agreement that provided the British fur traders access to roughly 400 miles of Russian-claimed Alaskan coastline and the adjoining interior country. HBC in turn, agreed to pay a yearly lease in foodstuff provisions and otter pelts, to act as shipping agent, and to abstain from the trading of alcohol to Alaskan Natives.

George Simpson, governor of HBC North American operations, had sought the agreement to fulfill his agenda of obtaining a monopoly of the continental fur trade in the company’s Columbia Department, a territory stretching from Russian Alaska to Mexican California and from the Pacific Ocean to the Rocky Mountains. Similarly, the RAC hoped to drive Americans from “their” territory. The arrangement worked. American fur traders, whose profits dwindled in step with declining sea otter populations, virtually disappeared from the North Pacific Coast after 1841.

Although the “Russian contract” provided HBC with a fur-trading monopoly throughout most of their Columbia Department, the agreement indirectly supported a bourgeoning American agricultural economy in the Willamette Valley. When HBC agreed to supply the Russians with wheat, company leaders assumed that the HBC’s Puget Sound Agricultural Company would successfully meet the provisioning conditions from their Cowlitz and Nisqually farms. If the harvests were insufficient, it was assumed that HBC farms at Fort Vancouver or purchases from Californians around Yerba Buena (modern day San Francisco) could make up the difference. As it happened, the Russian demand for wheat often outstripped the available supply, since the Puget Sound Agricultural Company performed far below expectations.

During the early 1840s, most of the American settlers who arrived in the Willamette Valley via the Oregon Trail were in need of farming supplies, having lost or abandoned them during their travels. From the department’s headquarters at Fort Vancouver, McLoughlin, faced with the annual challenge of meeting the terms of the “Russian Contract,” provided needy settlers with the seed and tools along with credit for the purchase of food, clothing, and other requirements from the company store. McLoughlin then bought their surplus wheat at harvest time or allowed debtors to use their wheat as payment in-kind, giving them a much needed market.

Although McLoughlin’s actions were generous, they were not altogether altruistic. By providing credit and market access through Fort Vancouver he hoped to quell anti-British sentiment and to forestall the development of a competitive, American-run agricultural market. His decision to help Americans settle in the Willamette Valley, however, was looked at unfavorably by Simpson and the HBC board in London, who would have rather seen the American settlements “broken up.”

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.

Related Historical Records

-

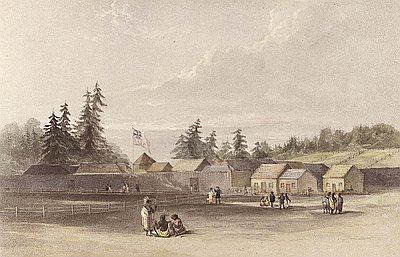

Drawing of Fort Vancouver

This hand-colored lithograph of Fort Vancouver was based on a sketch drawn by Henry James Warre in 1845 or 1846. The British government sent Warre, an army lieutenant, …

-

John McLoughlin to Hudson's Bay Co., 1828

John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department, wrote this letter to his superiors on August 10, 1828—two days after Arthur Black, one of four survivors of …