- Catalog No. —

- OHS Museum 4937 and 84

- Date —

- n.d.

- Era —

- Oregon Country before 1792

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River

- Author —

- Unknown

Plateau Culture Digging Stick

This digging stick originated most likely from the Columbia Plateau. The color is the result of fire-hardening, a technique often used to strengthen wood. Digging sticks were not unique to the Columbia Plateau. They have long been used by cultures around the world for gathering and horticultural purposes.

According to Native Americans of the Columbia Plateau, digging sticks have been used since time immemorial to gather edible roots like balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata), bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), camas (Camassia quamash), and varieties of biscuitroot (Lomatium). Typical digging sticks were—and still are—two to three feet in length, usually slightly arched, with the bottom tip shaved off at an angle. A five to eight inch cross-piece made of antler, bone, or wood fits perpendicularly over the top of the stick, allowing the use of two hands to drive the tool into the ground. Since contact with Europeans in the nineteenth century, Native Americans have also adapted the use of metal in making digging sticks.

Historically, on the Columbia Plateau, labor in Native American communities was divided between men and women. The primary responsibility of men was hunting and fishing, whereas women were responsible for child-rearing, camp maintenance, clothing production, and the gathering and preparation of foodstuffs. At times, men and women did work outside of their traditional gendered roles, but with the exception of male slaves, young boys, or berdache—a term French-Canadian fur trappers used to describe men and women who took on the appearance and roles of the opposite gender— men were typically not involved in food-gathering activities. Although scholars have historically focused on the role of salmon fishing in the indigenous economies of Columbia Plateau, the foods gathered by women were equally important. Prior to the loss of gathering grounds to agricultural development in the nineteenth century, gathered foods accounted for approximately half of the caloric intake of Native American communities on the Plateau.

Further Reading:

James, Caroline. Nez Perce Women in Transition, 1877 – 1990. Moscow, Idaho, 1996.

Hunn, Eugene S. Nch’i-Wana “The Big River”: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle, Wash., 1990.

Ackerman, Lillian A., ed. A Song to the Creator: Traditional Arts of Native American Women of the Plateau. Norman, Okla., 1996.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

Indian Burning in the Willamette Valley

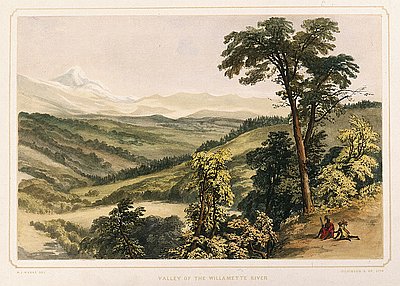

The earliest illustrations and written descriptions of the Willamette Valley, like the 1845 painting, Valley of the Willamette River, by Henry Warre reproduced here, depict a landscape of …

-

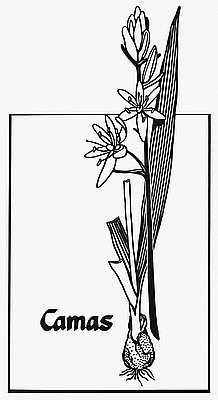

Camas

This drawing of the common camas (Camassia quamash ) was produced for the Oregon Historical Society by staff artist Skip Enge. The blue flowers of the camas, a …