- Catalog No. —

- Mss 1585

- Date —

- July 8, 1960

- Era —

- 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Black History, Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society, Stella Maris House Collection

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- E. Shelton Hill, Urban League of Portland

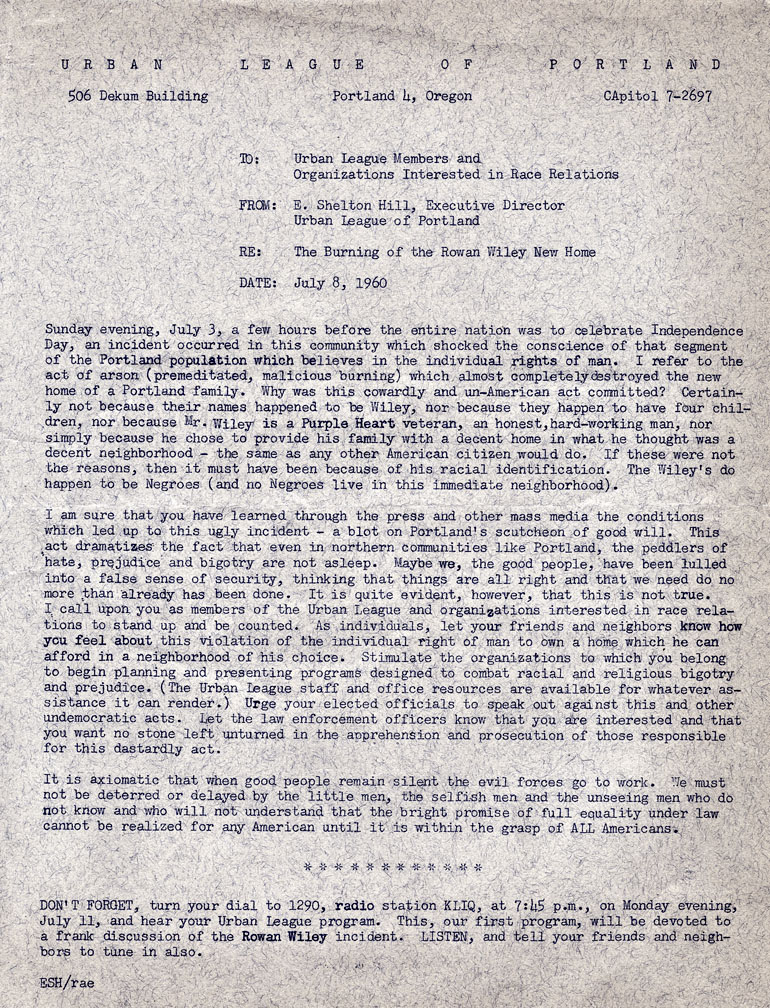

Wiley Family Housing Struggle

This memo was distributed by the Urban League of Portland in response to the race-based burning of the Wiley family’s newly constructed home in Portland’s Parkrose neighborhood.

Soon after moving to Portland in 1957, Rowan and Parthina Wiley began a search for a suburban home. They first attempted to purchase a home in a housing plan then under construction near SE 134th and Mill. Because Parthina was light-skinned, red-haired, and didn’t have prominent “Negroid features,” she passed as a white woman, easing the initial home-buying negotiations. However, once it was discovered that Rowan was not white, the general contractor refused to build their home, and their loan application for $11,000 was denied even though they offered $5,300 as a down payment. The Wileys appealed to Oregon’s Bureau of Labor, Civil Rights Division, to investigate their case, and in April 1960, the state filed a discrimination claim against the bank, realty, and construction companies involved. The state charged the companies with violation of Oregon’s Fair Housing Act of 1959, making the Wiley’s claim of discrimination the first test-case of the new legislation.

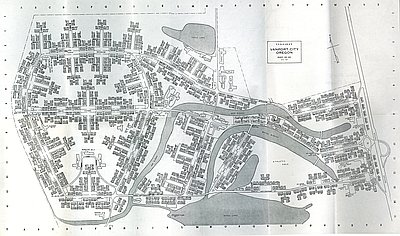

The Labor Commission sided with the Wileys and ordered all of the offending parties to cease and desist their discriminatory practices, giving them twenty days to deal with the family in good faith. However by then, the Wileys had purchased a plot of land in the Parkrose neighborhood, where they had begun building a new home. As before, things went smoothly while Parthina took care of business, but things changed once a future neighbor saw the African American couple inspecting the progress on their home. Neighbors alarmed at the prospect of “Negroes” living in their all-white neighborhood, organized and enlisted the support of the Richland Water District’s board of directors, who deemed the Wiley family’s new home in violation of the district’s sanitary regulations.

In March, the Wileys received a letter from the Richland Water District’s attorney, notifying them that their home and it’s sewage was located too close to one of the district’s wells and that unless they sold their property to the district, efforts to have it condemned would proceed immediately. After unsuccessfully attempting to negotiate with the water district, the Wileys filed suit in U.S. District Court for an injunction against the condemnation. In June, U.S. District Court Judge William G. East awarded the Wileys with an injunction against the Richland Water District.

On July 3rd, an arsonist doused the Wileys’ unfinished home in gasoline and set it ablaze resultingin approximately $7,000 to $9,000 in damages. Undeterred, the Wileys began rebuilding immediately. By that September, construction was complete and the Wileys moved in. Years later, Rowan Wiley, Jr., reflected “When we were kids, living in the neighborhood, other kids wanted to play with us and then had to hide so their parents wouldn’t see them….By the time we were all in junior high and high school, we all lived pretty much in harmony.”

Further Reading:

Meyer, Stephen Grant. As Long As They Don’t Move Next Door: Segregation and Racial Conflict in American Neighborhoods. Lanham, Md., 2000.

Yinger, John. Closed Doors, Opportunities Lost: The Continuing Costs of Housing Discrimination. New York, N.Y., 1997.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

War Housing and Vanport

When war broke out, Portland was the only city on the West Coast without a public housing authority, yet it faced the most rapid increase in war workers …

-

Fair Housing in Oregon Study

This case study was included as an appendix by the League of Women Voters of Portland in A Study of Awareness of the Oregon Fair Housing Law and a …

-

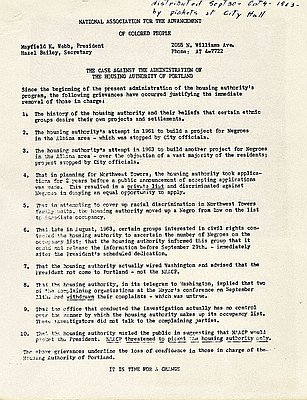

NAACP Flier Protesting the Housing Authority

This flier was distributed by protesters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on September 30 and October 4, 1963, at Portland’s City Hall …