- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 23436

- Date —

- 1956

- Era —

- 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Coast

- Author —

- William V. Wells, Harper's Monthly Magazine

Beach Gold Diggings

This sketch was published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in October 1856. It shows gold miners working black sands near Randolph, a short-lived mining town located north of the mouth of the Coquille River.

Gold-bearing black sands can be found from California’s Gold Bluff north to Washington’s Gray’s Harbor. Oregon’s South Coast contains the highest concentration of these auriferous sands, darkened by magnetite and other heavy minerals like chromite, zircon, and platinum. These minerals were carried to the ocean by the rivers that drain the Coast Range. Waves deposited the heavier minerals on the beach while lighter sands, composed primarily of quartz and feldspar, were swept back to sea.

One of the richest deposits of auriferous sands was located several miles north of the Coquille River at the mouth of Whiskey Run Creek. John and Peter Groslius, two brothers of French-Canadian and Indian descent, are generally credited with discovering this deposit in the winter of 1852-1853. Word quickly spread and by 1854 there were hundreds of men working the sands around Whiskey Run in search of gold.

The miners quickly constructed a ramshackle village—named after Virginia emigrant John Randolph—complete with saloons, stores, and restaurants. Randolph’s boom was short lived, though. A massive storm obliterated the black sands during the winter of 1854-1855. “The great sea,” historian Elwood Evans wrote in 1889, “that had deposited untold wealth upon its shores in the previous season, with its usual capriciousness removed it all the following winter.”

In the fall of 1855, writer William V. Wells traveled across southern Oregon, writing about the people he met and the places he saw for Harper’s Monthly. He described Randolph, the population of which had been reduced to nine adults and a handful of children. Wells noted that many of the makeshift buildings had been torn apart for firewood. “What a picture!,” he wrote. “A town springing from nothing--growing—culminating in its career of prosperity, and burned as fuel in its decadence!”

Although Whiskey Run was no longer productive, other South Coast beaches continued to offer rich diggings, including those at Ophir, Pistol River, Port Orford, and the aptly named Gold Beach. Commercial beach mining continued until World War II, when the federal government halted gold mining in order to focus on minerals needed for the war effort. Most of the South Coast’s gold mining operations did not reopen after the war. Although no longer commercially viable, the South Coast’s black sands still attract recreational prospectors hoping to strike it rich.

Further Reading:

Meier, Gary. “Oregon’s Gold Coast.” Oregon Geology 53, 1991: 99-100.

Orr, Elizabeth L., William N. Orr, and Ewart M. Baldwin, Geology of Oregon. Dubuque, Iowa., 1992.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.

Related Historical Records

-

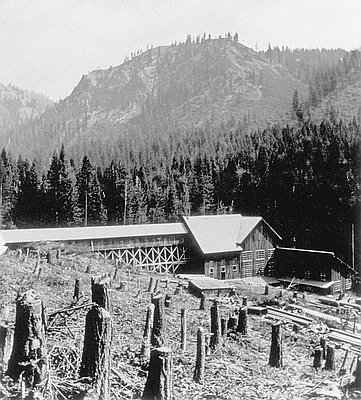

Gold Mine at Cornucopia, c. 1888

The photograph, probably taken by Martin M. Hazeltine of Baker City in the late 1880s, shows a stamp mill used to process gold-bearing ore near Cornucopia. The gold …

-

Gold!

In 1848, two years after Lindsay Applegate traveled through the Rogue River Valley, the discovery of gold in Sutter’s Mill, California, brought prospectors through southwest Oregon. In 1850 …

-

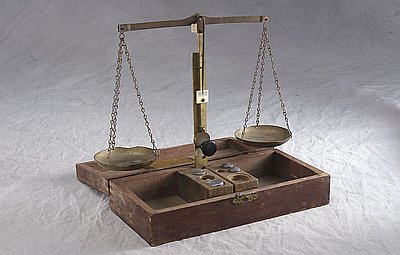

Gold Scales

There is some disagreement among historians as to exactly when and where gold was first discovered in southwestern Oregon, although many credit James Cluggage and Jim Poole, a …