- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 12192

- Date —

- circa 1904

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Agriculture and Ranching, Environment and Natural Resources, Oregon Trail and Resettlement, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Central Northeast

- Author —

- Unknown

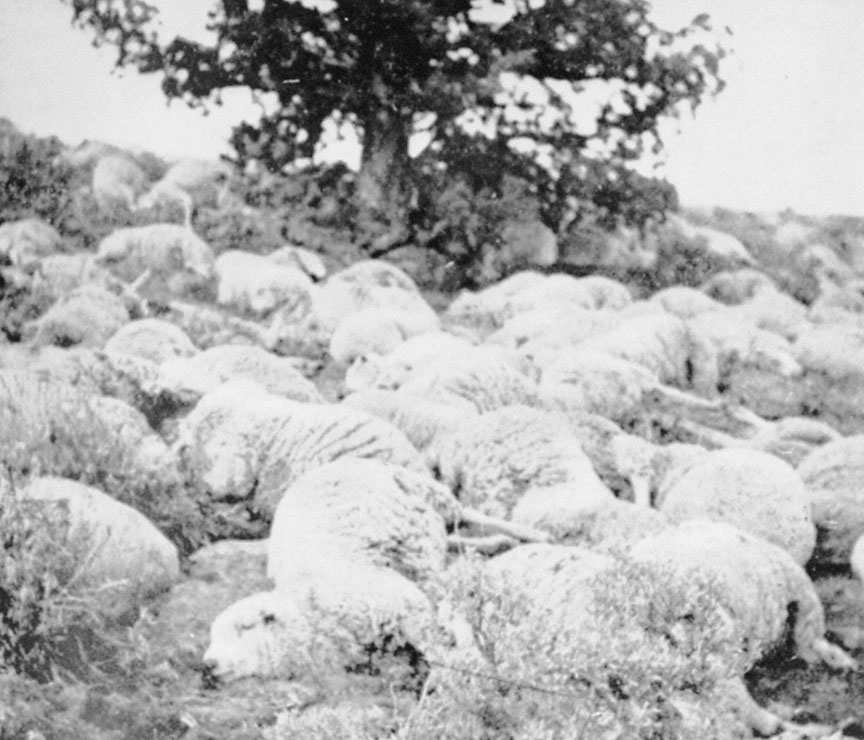

Central Oregon Range Wars

Following the forced re-settlement of the region’s Indian groups onto reservations after the Civil War, the grasslands of Eastern and Central Oregon became available for agriculture and livestock. As “open ranges,” these lands were traditionally available for all locals to share. The 1880s and 1890s proved particularly suited to the development of large cattle herds and sheep flocks as new rail lines allowed producers to ship both wool and cattle to the expanding markets across the United States. As a result, the number of sheep and cattle east of the Cascades increased dramatically. Since no legal statutes existed at the time to restrict usage, the rapid, unregulated exploitation of the grasslands resulted in overgrazing. Between 1885 and 1910 the number of sheep in Wasco County was approximately 130,000. Given such numbers, the range was unable to regenerate itself, and became increasingly degraded.

By the late 1890s, growing tensions between cattle ranchers and sheepmen over control of the open ranges led to a series of disputes known as the “range wars.” Cattlemen themselves held sheepmen in contempt for two specific reasons. Unlike cattle, sheep will eat weeds, also known as forbs, in addition to native grasses. As a result, the sheep stripped a landscape of its plant life, leaving nothing edible behind. Additionally, the equestrian culture of the cattlemen viewed sheepherders with disdain because the herdsmen tended animals on foot rather than on horseback. The expansion of wheat farming in Central and Eastern Oregon during this same period exacerbated competition for the range lands.

The range wars in Central and Eastern Oregon initially involved threats and scattered property damage. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, these incidents escalated to the burnings of sheep camps, and direct violence, including the clubbing, poisoning, and shooting of sheep. Violence perpetrated by groups of vigilante cattlemen reached a climax in the years 1904-1906. In April 1904, 2,300 sheep were killed in a single night in Lake County. In May 1904, a delegation of sheepmen from Antelope in eastern Wasco County traveled to Crook County in an effort to reach an agreement with the cattle ranchers of central Oregon. This attempt was unsuccessful and a few days later, 150 sheep were shot near Mitchell, located fifty miles southeast of Antelope. Additional incidents of sheep shooting occurred in Central Oregon that summer. The region’s sheepmen continued to advocate a non-violent resolution to the conflict, calling on state officials to act in order to stem the violence. In response, a group of cattlemen calling themselves the Crook County Sheep-Shooting Association urged the governor and state officials not to meddle in the affairs of “our province.”

The range wars gradually dissipated following changes in both government regulation and land ownership. In 1906, the federal government began regulating the use of public lands. Both cattlemen and sheepmen adjusted to the closure of the open range by purchasing land tracts, and by creating corporations that could support the higher costs of land ownership and more intensive production methods.

Further Reading:

Linley, William R. “From Oregon’s Range War to Nevada’s Sagebrush Rebellion.” Journal of the West 38, 1999: 56-61.

McGregor, Alexander Campbell. Counting Sheep: From Open Range to Agribusiness on the Columbia Plateau. Seattle, Wash., 1982.

Ostler, Jeffery. “The Origins of Central Oregon’s Range War of 1904.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 79, 1988: 2-9.

Written by Melinda Jette, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

Central Oregon

The Cascade Range divides the rainbelt of the Willamette Valley from the drier plains and open rangelands of central Oregon. Volcanic activity thousands of years ago left lava …

-

Central Oregon Sheepherders

This photograph depicts a group of sheepherders in Central Oregon during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. In the years following the Civil War, large, open tracts …

-

Union Stockyards Cattle Show

People and animals lined up for a livestock show on the grounds of the Portland Union Stockyards. The first part of the twentieth century was a busy time …