Jacksonville: The First Town

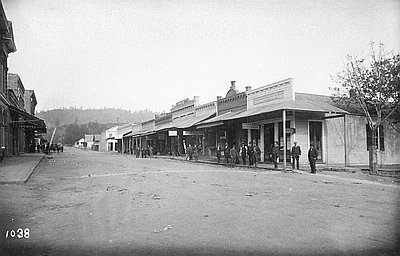

Soon after two prospectors found gold in Rich Gulch, a new mining camp emerged near the gold strike. On January 12, 1852, the Territorial Legislature set apart Jackson County from Lane and Umpqua Counties and named the camp—called Jacksonville— the county seat. Within a short time, the town was widely known as the most important community in the southern part of the territory.

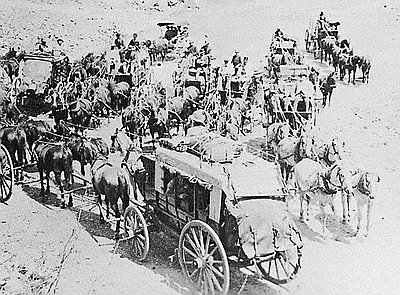

As a vital business and political center, Jacksonville attracted many individuals who would figure prominently in the region’s development. Farmer, vintner, and photographer Peter Britt (1819-1905), for example, opened a photography studio in Jacksonville in 1852 and for the rest of the century photographed the area’s residents, buildings, and landscape. His photographs recorded the town’s development, and his portraits of southern Oregon residents reveal details of dress and cultural customs. Beginning in 1860, C.C. Beekman—Wells Fargo & Company’s representative and the owner of southern Oregon’s only bank—transported gold shipments over the stage route that linked Jacksonville with Sacramento and Portland.

Jacksonville’s early newspapers reflected the local and territorial political tensions that pervaded the region before the Civil War. With a large number of Jackson County residents from border states such as Kentucky and Missouri, Southern sympathizers predominated. Like most residents of the Oregon Territory, historian Jeffrey LaLande writes, most Jackson County residents were Democrats and partial to Jacksonian democracy and states’ rights.

The Oregon Sentinel’s editor James O’Meara, an outspoken Southern Democrat, conveyed passionate support for states’ rights and the South. Like other Northwest newspapermen, his journalism incorporated the vituperative approach widely known as the “Oregon style.” Editorials in this mode, exemplified in the writings of Oregon Statesman editor Asahel Bush, eviscerated the individuals on whom they focused. Bush, for example, described a critic of his newspaper in 1853 as a “man whose very countenance is redolent with filth, from whose polluted lips it drips in an incessant stream, who has festered in brothels and wallowed in gutters half his life.”

While gold mining declined in the region during the 1870s, Jacksonville looked forward to the arrival of the Oregon and California Railroad. Residents confidently invested in new homes and businesses and proudly watched construction of the county’s new courthouse. When the line reached the Rogue Valley in 1883, however, it bypassed the community when Jacksonville officials, secure in their belief that the railroad could not survive without the town, declined to purchase a right-of-way or to donate toward construction expenses. The railroad company laid the track five miles to the west, where Medford soon sprang up on the valley plain.

Towns developed around depots at Grants Pass, Phoenix, and other locations, and the line’s completion in 1887 at Ashland diminished the isolation that had marked the region’s pioneer era. As new centers of trade between Sacramento and Portland, Jackson and Josephine Counties anticipated a booming economy and growing communities. No longer the commercial center of southwestern Oregon, Jacksonville’s influence soon faded.

© Kay Atwood and Dennis J. Gray, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.