- Catalog No. —

- Mss 1226

- Date —

- 1841

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Research Library

- Regions —

- Willamette Basin

- Author —

- George W. LeBreton

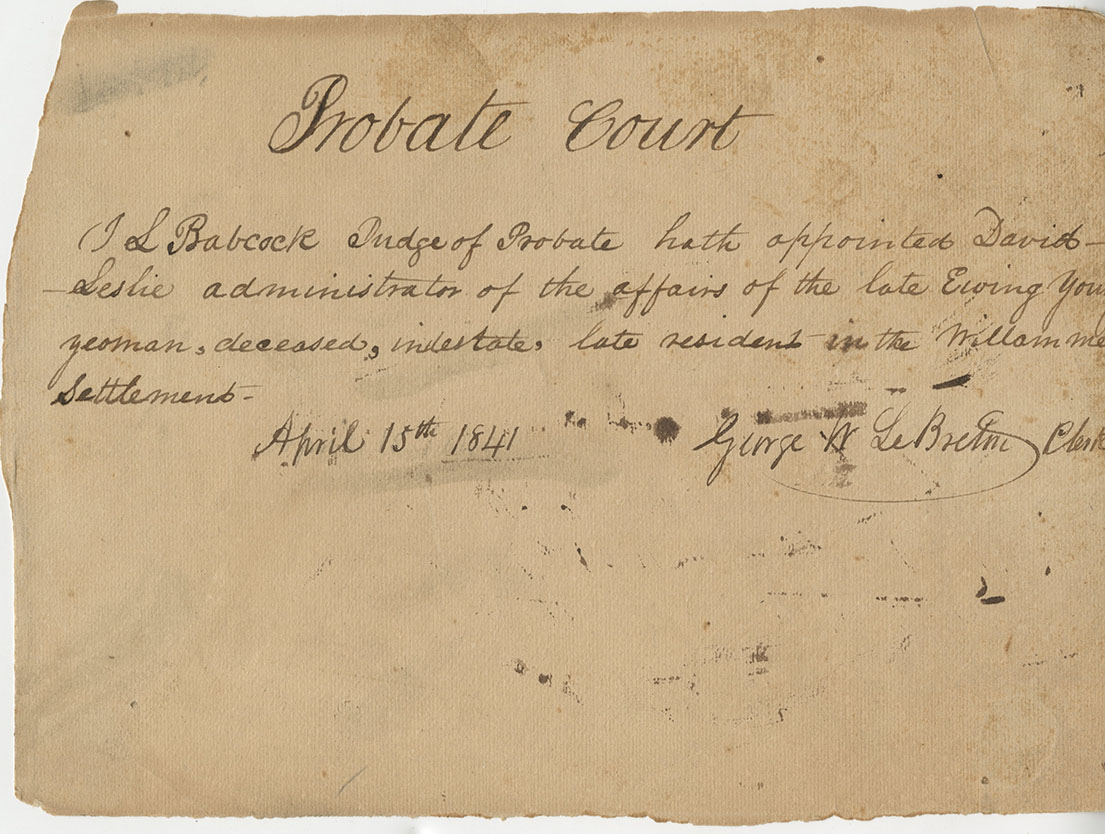

Probate Court: David Leslie assigned executor of Ewing Young's estate

This scrap of paper—handwritten, covered in centuries-old smudged fingerprints—is a remnant of the first significant attempt to create a functioning non-Native government in Oregon Country. The four men named in the 1841 document—Ira L. Babcock, David Leslie, Ewing Young, and George W. LeBreton—served as initiates in what would become the state system.

The United States did not claim Oregon Country outright until 1846, when it signed a treaty with Great Britain to settle the northern border of what is now Washington State along the 49th parallel. Until then, the Pacific Northwest was variously dominated by Native groups, missionaries, and American and British-Canadian fur trading companies. The missionaries and fur companies maintained their own orders of a sort that mimicked government bureaucracy and meted out legal-like punishments (Fort Vancouver’s Hudson’s Bay Company, for example, had a jail cell). You had to travel east to U.S. territory to record marriages and divorces or wait for a traveling judge. Many simply made declarations of partnership and called it good, a process that worked for contracts of all kinds in the region.

But ad hoc legal arrangements were insufficient for the most urgent concern of white settlers in Oregon Country: clear title to land. The ambiguity of American and British co-occupation of Oregon Country made land claims tenuous, at best, and irrelevant at worst. You could hire a surveyer, make a map, record lot sales on paper, sign and mark and sign again, but in the end you had an unenforceable interest in a piece of land that was not recognized by any state or federal government. You had to hope that your fellow settlers accepted the imaginary lines drawn around your claim as real; in return, you would do the same for their imaginary lines. If you left your claim unattended for too long, you could return to find a new claimant, also clutching ownership documents in his hand.

Still, non-Native American settlers expected their land lines to become real as soon the United States claimed Oregon Country and surveyed the land, which they hoped would happen soon. The pattern of U.S. expansion to the West made this expectation reasonable. Land claimants had always jumped ahead of federal surveys in anticipation of the government accepting their boundary lines, as-is (more or less), a practice that was codified in U.S. law by the 1841 Pre-Emption Act. In time, you could file a new claim to the Government Land Office in Washington, D.C., for land you had lived and built on for a decade or more. The federal government would eventually catch up.

But international affairs were far from settled in 1841, when white settler Ewing Young died without a will (intestate) or known heirs. He had claimed a lot of property, much of it with wealth-producing mills and farms. Young was the first settler of wealth in Oregon Country to die without instructions for how to distribute his estate, and his lack of planning left his neighbors in a quandary. What law do you follow in a land with no laws?

A committee was formed and positions created—necessarily, a Supreme Judge with probate powers (Dr. Ira Babock, a member of the Great Reinforcement); a clerk to record legal decisions (sea merchant George LeBreton); and a sheriff and constables to enforce the judge’s decisions. Babcock—now Supreme Judge Babcock, lately of New York—used his home-state laws as a guideline to appoint Methodist missionary David Leslie as executor. Leslie sold Young’s property, distributed debts and paid expenses. Asa Lovejoy eventually took over as executor and finalized the estate, dedicating a portion to building a jail in Oregon City. In 1854, Young's son, Joaquin, petitioned Oregon's territorial government for his inheritance; he settled for about $5,000.

That initial committee met again, and again and again, until its expanded membership formed Oregon’s Provisional Government in 1843, which included an executive committee (which transitioned to a single governor), legislative representatives distributed geographically, and the bureaucratic offices of secretary and treasurer. One of their first acts was to distribute land to white settlers, with the formality of a Provisional Government land claim.

Those land claims, significantly, were only legitimate in the eyes of the people who accepted the Provisional Government, a group of men with self-proclaimed authority modeled after familiar U.S. state systems. The government, and the laws it passed, were unrecognized by any nation until 1848, when the Territory of Oregon was created by Congress. Oregon’s territorial representatives worked in Washington, D.C., to protect provisional land claims and were largely successful. Significantly, the federal government in 1850 passed laws designed to remove another impediment to white land claims: the rights of Native people who had lived in the region for thousands of years. The primary purpose of the treaty system was to extinguish land ownership by sovereign Indian nations.

This small record of Young’s estate tells us much about how essential social contracts have been to nation-building. The intangible is made real, and enforceable, by a few strokes of a pen. The weight of history on this document—a scrap of paper, with writing by a self-appointed clerk on the order of a self-declared judge on land undeclared by any nation—is almost crushing.

Further reading:

Robbins, William. Oregon: This Storied Land. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2005.

Heider, Douglas, and David Dietz. Legislative Perspectives: A 150-Year History of the Oregon Legislatures from 1843-1993. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2000.

Robertson, James Rood. “The Genesis of Political Authority and of a Commonwealth Government in Oregon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 1.1 (March 1900): 3-59.

Holmes, Kenneth L. Ewing Young: Master Trapper. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1967.

Written by A. E. Platt, Oregon Historical Society, 2021

Related Historical Records

-

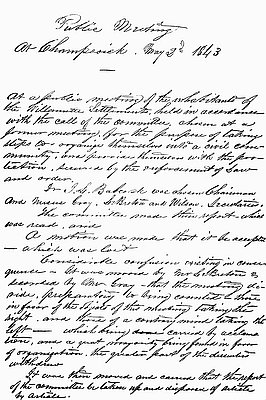

Public Meeting at Champoeg, 1843

On May 2, 1843, Willamette Valley settlers met at Champoeg to vote on the formation of a provisional government. The minutes recorded by George Le Breton recount the vote in favor …

-

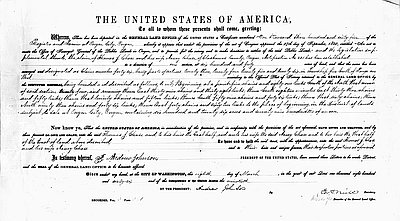

Oregon Land Donation Claim Notification

This image shows a certificate issued March 8, 1866, that grants 640 acres of land in Clackamas County to Thomas J. Chase and his wife, Nancy. The document …

-

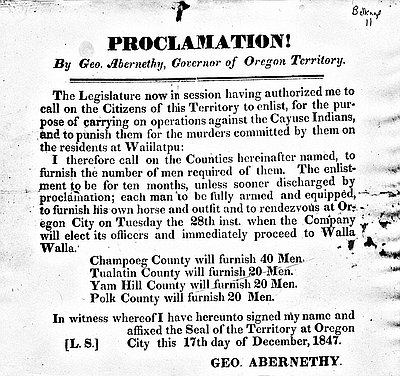

Proclamation from Governor George Abernethy

Oregon Provisional Governor George Abernethy issued this proclamation for the raising of a voluntary militia following an authorization from the Oregon Provisional Legislature. The legislature’s intent was to respond …