Challenges Ahead

In 2005, Lakeview appeared to be banking on improved business resulting from construction of Oregon’s newest prison. The project would create new jobs and bring new residents to the town. (Burns became home to the new Eastern Oregon Youth Correctional facility in 1997, operating in one of the few buildings left from the Hines sawmill.) With a declining and graying population, as well as with its high unemployment levels—well over 15 percent in 2004, compared to an Oregon average of 7.2 percent—Lake County, like its two neighboring counties to the east, faces economic and social challenges in the years ahead. Southeastern Oregon’s average household income ranks well below the state average.

Jordan Valley demonstrates some of the looming hurdles. With the closing of its only grocery store in 2001, Jordan Valley residents, numbering fewer than 250, must travel nearly fifty miles to Homedale, Idaho, on the Snake River, for basic supplies; the nearest hospital is in Nampa, an hour-and-a-half drive away. Harney County’s vast distances accounts for one of the only public boarding schools in the nation; Crane Union High School is a comparatively expensive educational institution to maintain. The relatively few schoolchildren who reside in the southern third of Malheur County ride all the way to McDermitt Elementary School, situated across the state line in Nevada.

Ethnic diversity, certainly never entirely absent in southeastern Oregon, has lately increased. Nearly one-third of Malheur County’s population is now Latino, although the overwhelming majority live in the well-populated irrigated valleys adjacent to the Snake River, not in the high desert proper. Harney County’s Latino population is slightly under 5 percent of the population, most in and close to Burns, and Lake County has slightly over 5 percent, most in and near Lakeview. This influx of Latino immigrants—most from the Republic of Mexico—has been drawn to the area by jobs, such as those at Lakeview’s wood-door plant, low-wage agricultural jobs, and lower-paid work as housemaids at local motels. Although currently very small in number and percentage of total county population compared to many other areas of the Northwest, their arrival in southeastern Oregon represents a substantial increase from previous decades and has marked a noticeable change for older local residents. These particular newcomers are contributing to the high desert’s ever-changing social fabric. Decades after Californio vaqueros first drove cattle onto Oregon’s high desert, Spanish is once again spoken here; as with the Basques a century ago, local schools are adapting to a new generation of students for whom English is a second language.

Northern Paiutes, of course, continue to call southeastern Oregon their home. Those Paiutes who had initially settled at Fort McDermitt, located just south of the Nevada state line, in the 1860s and 1870s included the famous interpreter, inter-cultural diplomat, and teacher Sarah Winnemucca; these people clustered around the Army post for security. In later years, eventually joined by other Paiutes who had been removed to Washington Territory after the Bannock War and closure of the Malheur Reservation, some of them took up allotments of land nearby. In 1889 the U.S. government created the Ft. McDermitt Reservation from these and other parcels. A majority of this reservation’s land base—over 18,000 acres—consists of sagebrush steppe in Malheur County on the Oregon side of the border, dotted here and there with modest homes. The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe Indians achieved federal recognition as a self-governing tribe in 1936.

Lake County actually has the highest percentage of Native American residents of the high desert’s counties, most of them Paiute descendants who are members of the Klamath Tribes and live in the westernmost part of the county.

A few of the Northern Paiute—particularly members of the Wadatika band who were allowed to leave Washington’s Yakama Reservation for their Great Basin homeland in the 1880s—returned directly to the Harney Valley. Here, the government established “Indian allotments,” some of them within the former Malheur Reservation east of Burns. During the early twentieth century some Paiute returnees later moved to the northern outskirts of Burns, a few of them finding work in the Hines sawmill and others taking on low-paid part-time ranch jobs.

With a 771-acre parcel just north of Burns, purchased in 1935 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs from private land owners, the “Burns Indian Colony”—as it was known by the BIA for many years—became a fixture of northern Harney County. It has remained tangible proof that the Northern Paiute did not, as some local whites had previously claimed, “disappear.” Paiute women wove baskets and sewed beaded-buckskin moccasins for sale to the few tourists that stopped in Burns. Small-scale ranching, as well as seasonal work for the Forest Service and BLM, contributed to improved household income after World War II. In 1968 the Burns Paiute Tribe sought and received acknowledgment from the U.S. Department of Interior as a federally recognized, self-governing tribe. It received full title to its small reservation, and has since acquired additional lands and constructed a the Old Camp Casino, which eventually closed. Situated far off the beaten track, economic development remains a difficult hurdle for the Burns Paiute Tribe.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

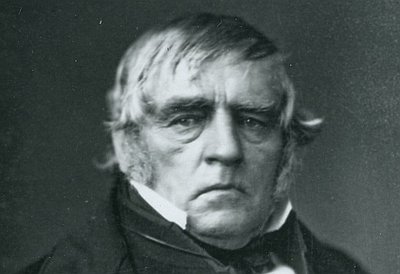

Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon

In June 1855, Joel Palmer, Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, met at The Dalles with representatives of the various Upper Chinookan and Sahaptin peoples of the mid-Columbia River …

Mexican Laborers Weed Sugar Beet Field

This photograph shows Mexican citizens weeding and thinning in an unidentified sugar beet field in Oregon, probably in Malheur County, during World War II. In 1942, the United …

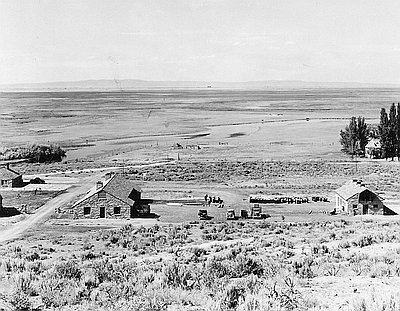

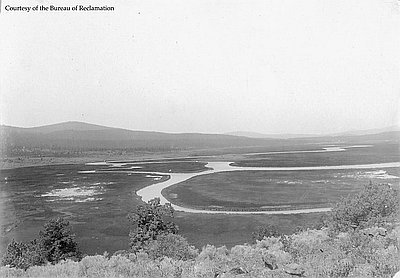

Malheur Migratory Bird Refuge, 1937

This photograph was taken in August 1937 by Ralph Gifford, a photographer for the Oregon State Highway Department. It shows the Malheur Migratory Bird Refuge, which was designated …