Recreation of Community Divisions—Women

After about 1900, changes in the structure of the industry and American immigration law worked against continuing to hire large numbers of Chinese in the canneries. While in other canning districts, large numbers of Japanese Americans, Filipinos, and Native Americans entered the workforce, in Oregon, especially on the Columbia River, most of the non-Chinese workers were Euro-American women. Canners turned to women because of a widely held belief that they worked best at light, quick, and repetitive tasks and because the concentration of plants allowed canners to turn to Euro-American women as workers. After 1890, women from local Euro-American families worked at piece and hourly rates on the sliming lines and filling tables, some as regulars and some as “extra hires” during the peak of the season. By the 1910s, women comprised up to 25 percent of the crews in Astoria canneries; that percentage increased in subsequent decades. Ideas about cannery work as being ideal for women persisted, and in 1934 Director of the U.S. Women’s Bureau Mary Anderson earnestly explained to federal officials that “much of the work done by women in salmon canning requires great speed and care and is of a type men cannot perform as satisfactorily as can women.”

Such assumptions affected the organization of the workplace and guided the canners’ approach to women’s wages. Canners paid women as little as possible, typically less than any men in the plants. Some women earned “expert” wages, but short-term employees, younger women, and women with less status in their local communities most often worked as “apprentices” for 25 to 40 percent less than the experts. Of the thirty-four women who worked as can fillers in the Altoona, Washington, plant in 1941, for example, the company classified nineteen as apprentice fillers and fifteen as expert fillers.

Euro-American women’s reasons for participating in cannery work varied widely. Some were simply looking for wage work and family income. Working-class and immigrant families promoted women’s work, unlike many of their middle-class “Victorian” counterparts. Others focused on the sense of personal pride obtained from a job well done. Annie Brunzel, who worked in a Puget Sound cannery, explained: “I was very fast with my hands….Boy, did I think that was something.” Others found the sociability of cannery work a draw in spite of the fast-paced, routine, and repetitive work. The work provided a place in which young women could be brought in the social networks of their communities. “We would belong to the crew,” Eva Mathews Lemaister explained, and it was “hard to get on…if you didn’t belong in the crew.” The informal organization of the workplace reflected the community’s social divisions, and they were hired through family and friendship networks. A good word from a crew leader to a foreman or superintendent assured a position, and a lukewarm or confidentially negative response meant no job or a poor one. The cannery workplace largely reflected the Euro-American community’s social order.

Especially on the Columbia River, white men’s concerns as fishers dominated women’s activities in the plants. As one U.S. Women’s Bureau observer noted, “Nearly all the women…were housewives or daughters of local families or of the fishermen’s families. Simply being married to fishermen did not automatically make women in those areas subordinate to men, but on the Columbia River, leaders of the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union (CRFPU) asserted an intense patriarchy and union loyalty. Until 1933, the powerful union made no effort to provide regular representation for cannery workers, but “The Big Strike” that year forced it to organize white women, although not Asian American men, in the Cannery Workers Auxiliary, using them to shut down the plants until canners met demands for increased fish prices. When women registered complaints in subsequent years, CRFPU officials brushed them aside as “gossip” and “nagging.” In addition, the demands for loyalty to the CRFPU limited the ability of women cannery workers to develop strong ties with their counterparts in coastal Oregon and Washington, Puget Sound, and Alaska canneries.

It would be misleading to assert that all women in the plants were white. Some were Chinese American, typically the daughters, wives, and other relatives of contractors. In the mid-1920s in one Astoria plant, for example, Irene and Constance Wong and a Mrs. Chan worked at filling tables alongside the wives and daughters of Euro-American fishers. While relatively few in number, Japanese American women worked in Oregon’s salmon canneries, and in some cases intriguing gender relations emerged. In 1926 at Astoria, for example, nine Japanese immigrant couples worked for the Columbia River Packers Association Elmore Cannery. The women worked as slimers and can fillers, and their husbands worked along the canning line at heavier tasks. Company records indicate that Mrs. Hanaoka and Mrs. Ikagami worked alternate days. Based on patterns in British Columbia, this suggests that the two may have shared the task of childcare for the all the Issei couples working in the plant.

Beginning in the 1930s, union contracts on the Columbia River reveal that male “Oriental” labor earned separate treatment from white women’s crews and often better pay for similar work. Canners demanded that Asian American men hold skilled and semi-skilled positions. Moreover, Chinese foremen retained the power to hire and fire individuals in the Chinese crews. White cannery workers and fishermen could not dislodge them or dissuade companies from continuing to hire them. Only in the early 1950s, did patriarchal control and ethnic ties with women cannery workers break down enough so that cannery workers voted to affiliate with a union other than the CRFPU. Even then, they walked out of the plants in solidarity with the fishers during a contentious 1952 strike.

The interiors of the canneries were highly racialized and gendered places. Asian American men—in Oregon, largely Chinese and a few Japanese—struggled to assert their masculinity amid a host society that regularly forced feminine characteristics upon them. A few Chinese and Japanese American women worked in the plants, sometimes interacting with their Euro-American counterparts, sometimes not, depending on circumstances. Euro-American women found themselves tightly bound to the dictates of their fathers and husbands, occasionally breaking away and pushing their own agendas but as often supporting the efforts of the “family breadwinner.”

© Chris Friday, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

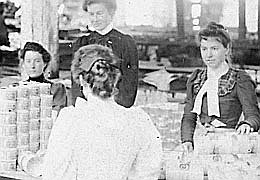

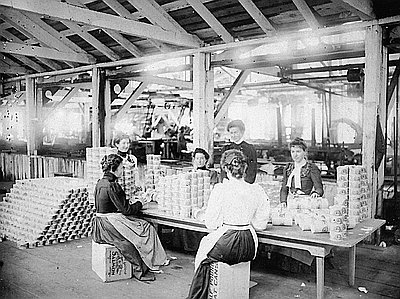

Women Cannery Workers

This photograph was taken by Portland photographer John F. Ford, probably between 1900 and 1902. It shows women labeling cans of salmon at the Megler Cannery in Brookfield, …

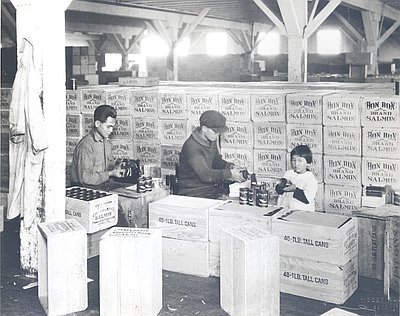

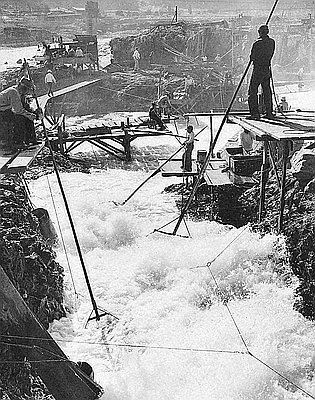

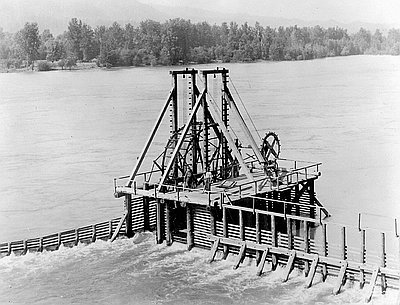

Eagle Cliff Cannery

This photograph shows the Eagle Cliff Cannery, located on the Washington side of the Columbia River about fifty miles upriver from Astoria. During the winter of 1866-1867, brothers …

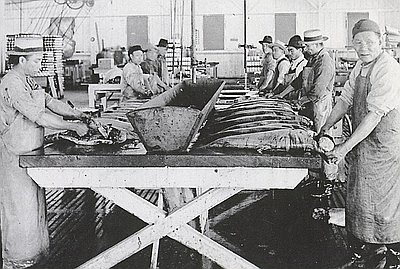

Chinese Cannery Workers near Astoria, Oregon

This stereographic image, printed by the Keystone View Company, has this description of the fish-cleaning process written on the back: “One [person] does nothing but cut off heads, tails, …