Whites Become Ethnics

Conflict had the potential to challenge that inclusion. The anti-unionist San Francisco paper used the fishermen’s immigrant status as ammunition and attacked the strikers by framing them as ethnically different, labeling them “a lot of Greek, Italian and other European peasantry calling themselves the Fishermen’s Union....[who] like their piratical ancestors...propose to take by force the property of others.” It is telling that, in resorting to ethnic name-calling, the newspaper chose Greek and Italian as labels, since there were only sixty-six Italians and fewer than thirty Greeks in Astoria in 1900. The strikers were largely Scandinavians, as they made up the bulk of the union membership. Yet Greeks and Italians were among the immigrant groups often stigmatized in the national press as particularly unsuited for citizenship. The paper’s choice to use these ethnic labels rather than more accurate ones was calculated to stigmatize the strike as un-American.

Yet the response of the Daily Astorian suggests just how locally accepted the immigrant fishermen were. It castigated such rhetoric as “reckless and indiscreet newspaper scribbling” and explicitly defined the immigrant fishermen as part of the “honest and law-abiding set of men” who made up Astorian society: “In the first place, the ‘Greek, Italian and other European peasantry calling themselves the Fishermen’s Union of the Columbia river’ are the men upon whose labor the welfare of the city of Astoria under present conditions mostly depends. Accident of birth is no crime. In any case, these men are not responsible for their nationality, neither does it follow that, because they are ‘European peasantry,’ they are outlaws and pirates.”

Interestingly, the editorial does not correct the San Francisco paper by explaining that the strikers were mostly Scandinavians but presents a defense of European immigrants in general. This pair of editorials vividly shows the ways in which ethnicity could be highlighted or dismissed in order to label a group as outsiders or to include them as part of the citizenry.

While ethnic identity was often used by outsiders as a negative label denoting difference, insiders frequently embraced the values, traditions, and cultural practices associated with their ethnic groups as part of their personal and community identities. Studies like historian Chris Friday’s Organizing Asian American Labor demonstrate the importance of such identities to Asian Americans in the canning industry.

In the related documents, the clearest example of an immigrant group’s expression of its ethnic identity can be found in the materials on Astoria. There, the heavy concentration of Finns, and of Scandinavians more generally, fostered strong ethnic ties that were expressed through cultural, political, and economic activities. The general acceptance of these northern European ethnics in the region and the absence of economic and legal restrictions on them such as those faced by the Chinese fostered these expressions of ethnic identity.

The development of significant clusters of immigrants from a particular country or region is a common pattern resulting from chain migrations. In the case of Astoria, Scandinavian immigrants followed one another in kinship and acquaintance groups to a place where they could engage in a familiar a occupation—salmon fishing. There, far more than in the inland Columbia River canning towns, the concentration of immigrants became pronounced by the turn of the century. By 1920, there were approximately 3,839 ethnic Finns in Astoria, including both immigrants and their children—over 27 percent of the town's population. Together with the Norwegian and Swedish Americans (first and second generation), these groups accounted for 45 percent of Astoria’s population.

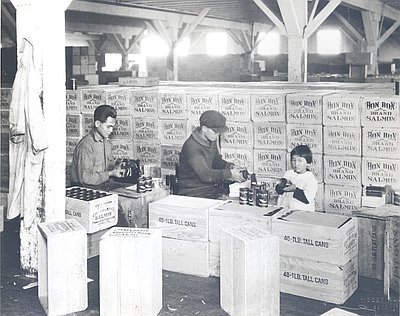

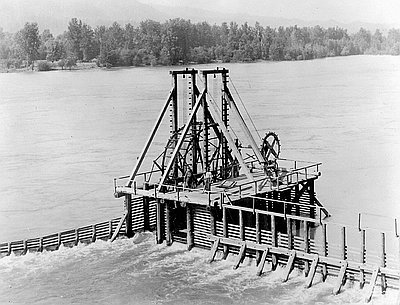

Not surprisingly, this strong presence led to a different ethnic dynamic than in the inland river towns, where no single group dominated and where the native-born far outnumbered the foreign-born. Their concentration in Astoria, and in a particular segment of its economy, allowed Finns to use their ethnic identity to empower themselves economically and politically by drawing on a strain of radicalism that they had brought with them from their homeland. While the documents here do not provide detailed information about the functioning of the Finnish Socialist Club, the photograph of the picnic suggests that it played a strong social function. It also likely reinforced the solidarity created by cooperative economic enterprises such as the Union Fisherman's Cooperative Packing Company and other institutions in the Finnish-dominated area known as Uniontown, including the Suomi (Finnish) Hall, the community meat market, and the sauna.

© Ellen Eisenberg, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Finnish Socialist Club Picnic, Astoria, 1922

This photograph shows members of the Finnish Socialist Club picnicking in Astoria in 1922. The Finnish Socialist Club was one of Astoria’s most prominent ethnic organizations during the …

Scandinavian Immigration

This undated photograph of a group in Scandinavian costumes was taken in Portland by a photographer documented only as “Erickson.” Between 1820 and 1920, more than 2.1 million …

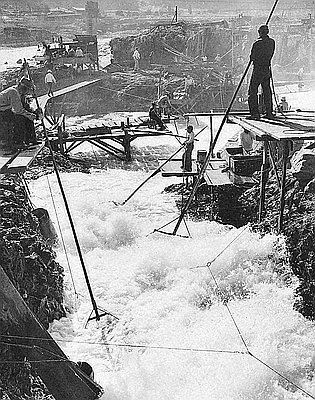

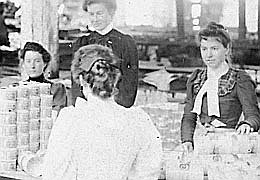

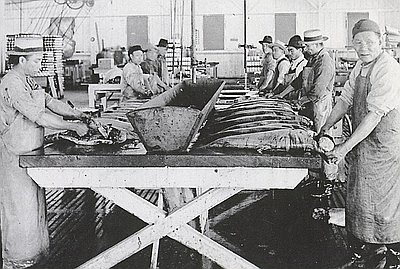

Chinese Cannery Workers near Astoria, Oregon

This stereographic image, printed by the Keystone View Company, has this description of the fish-cleaning process written on the back: “One [person] does nothing but cut off heads, tails, …