A Hard Country to Settle

Pillars of Rome formations at Owyhee Canyonlands

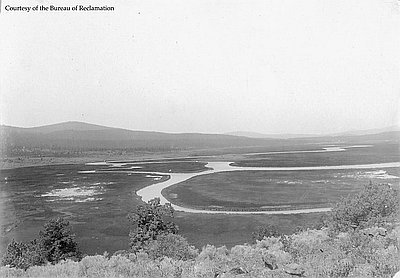

Lacking the rich gold or other precious-metal deposits of neighboring areas, southeastern Oregon’s development took a slower course. A few hardy settlers had begun grazing cattle herds in the region’s natural pasture bottomlands by the mid to late 1860s, developing their ranching operations near permanent watercourses.

Southeastern Oregon was largely settled by two separate streams of cattlemen, from Oregon and California. Stockmen from southwestern Oregon pushed the cattle frontier to the east, most of them driving their herds into what is now western Lake County and southeastern Deschutes County. Others came from California’s Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys and across northwest Nevada into present-day Harney and Malheur Counties, bringing immense herds of cattle with them. Some established huge ranches that took on the character of feudal fiefdoms.

Then, as now, control of water and the land adjacent to it was the key to survival. In some parts of southeastern Oregon, honest use of the homestead laws provided the legal means for desirable land to come into private ownership. Elsewhere, however, shady government land disposal deals (such as those that occurred in Warner Valley) as well as the outright abuse of homestead laws (such as the use of dummy homestead claims by ranch employees) brought thousands of acres of bottomland into the hands of wealthy entrepreneurs. By 1880, merchants and others willing to gamble on the prospects of the new country had founded a few small but important towns in the High Desert.

A significant number of southeastern Oregon’s early stockmen, particularly those who settled in Lake County in the 1870s, came from the older ranching country of the Rogue River Valley, around Jacksonville and Ashland. Seeking new spreads and plenty of elbow room, many of them brought fairly small herds and established modest-sized operations in the Silver Lake, Chewaucan River, Goose Lake, and Warner valleys. George Millican, a stockman from the southern Willamette Valley near Eugene, established a sizable ranch in the largely waterless country of present-day southeastern Deschutes County.

The smaller number of better bankrolled cattlemen from California generally headed for more remote locations east of Lake County, such as the Harney Valley, Donner and Blitzen River (named by a German-speaking army trooper for the severe thunder and lightning storm he witnessed there), Catlow Valley, Alvord Basin, and the upper Owyhee Basin. Their early ranches in Harney and Malheur Counties were something totally new to Oregon: they were huge livestock operations in terms of herd size, water rights, and acres; they were owned by distant investors in cities like San Francisco and Sacramento; and they were run on site by experienced junior partners or trusted employees.

California cattleman John Devine was Harney County’s first permanent settler in 1869. He and his partner, W.B. Todhunter, who remained in California to oversee operations in the San Joaquin Valley, established the great White Horse Ranch in the Alvord Basin, east of Steens Mountain. Soon, Todhunter and Devine cattle ranged well into the upper Owyhee country. The partners also developed the naturally irrigated Island Ranch on the north shore of Malheur Lake.

Devine, who dressed like a “Spanish grandee” in silver-studded leather riding gear and raced thoroughbred horses and greyhounds, brought a large crew of Spanish-speaking Californios, central California Indians who had grown up riding and herding on Mexican land grants. Peter French—junior partner and soon-to-be son-in-law of wealthy Sacramento Valley cattleman Hugh J. Glenn—arrived at the western foot of Steens Mountain in 1872, accompanied by his own vaqueros. French, who shared in the exhausting toil of the vaqueros, could be abrasive and strong-willed with competitors, sometimes to the point of recklessness. His P Ranch, centered on the marshes and streams of the Blitzen Valley and with headquarters at Frenchglen, became the seat of a vast cattle barony.

The firm of Riley and Hardin, owned by Amos Riley and James Hardin, with large ranches in California’s Shasta County and Nevada’s Quinn River Valley, built another such enterprise with headquarters just north of Harney Lake. The partners’ trusted superintendent, Isaac Foster, ran their Oregon operation. John Catlow, David Shirk, and other California cattlemen soon followed to Harney and Malheur Counties. In southern Malheur County, Pick Anderson arrived in the 1880s and developed one of the largest cattle and sheep spreads in the county. Farther south, Tom Turnbull started up a large sheep ranch in Barren Valley during the same period.

Southeastern Oregon’s largest and most powerful livestock operation, the California firm of Miller and Lux, arrived on the scene in the early 1880s, buying up herds and ranches from failing companies like Todhunter and Devine. The ZX Ranch, the largest such operation in Lake County, formed later in the century through the consolidation of smaller holdings in the Chewaucan Valley near Paisley. The MC Ranch, a big spread in the Warner Valley east of Lakeview, grew by similar means.

The nation’s first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869, passed across northern Nevada, and the new railroad’s shipping point at Winnemucca became a primary destination for many southeastern Oregon cattle drives. In the late 1870s, long-distance cattle drives eastward from the Oregon High Desert competed with those drives coming north from Texas to establish a new cattle empire on the northern Great Plains of Wyoming and Montana.

In 1878, the so-called Bannock War, which originated in southern Idaho, brought Shoshone and Bannock from the Snake River to the Owyhee Mountains, through the Jordan Valley area, and northwest into the Harney Valley. Hoping to find aid and refuge from U.S. Army troops on the Malheur Reservation, they joined with some Northern Paiute in skirmishes with ranchers, including Pete French at his Diamond Ranch.

For the Northern Paiute, their participation in this brief and futile war gave Oregon politicians a reason for demanding that the Malheur Reservation be dissolved. Many of people who lived there were removed to the distant Yakama Reservation in central Washington or to the Warm Springs Reservation in central Oregon. This removal became known among the Northern Paiutes as their “Trail of Tears.”

With the Malheur Reservation abolished, nearly 2 million acres of Harney Basin and upper Malheur River land lay open for settlement and grazing by ranchers. The resulting land rush brought more newcomers to northeastern Harney and northwestern Malheur Counties in the early 1880s and helped tip the balance against the area’s absentee-owned ranching operations. For Native people, it meant a rapidly declining portion of the region’s total population, as well as low-paid employment on ranches. By 1900, most of the Northern Paiute in the High Desert lived in three small communities: Fort McDermitt, just south of Owyhee County, straddling the Oregon-Nevada state line; Fort Bidwell, south of Lake County’s Warner Valley in the northeastern corner of California; and on the northern outskirts of Burns in Harney County.

By the 1880s, stockmen were running large herds of sheep and horses in the High Desert range. The demand for sheep wool was steadily growing, first by woolen factories in western Oregon and subsequently by northeastern Oregon’s Pendleton Woolen Mills. Conflicts between cattlemen and sheepmen over grazing were few in southeastern Oregon. On occasion, Lake County ranchers drew “deadlines” in the sand, beyond which any herd of sheep was exterminated by local buckaroos, but many ranches in the region raised both cattle and sheep, and local range wars amounted to little. The notable exception occurred from 1903 to 1906 near Benjamin Lake and Silver Lake, where bloody conflicts left several thousand sheep slaughtered and at least one person murdered.

Large herds of horses were also an integral part of the livestock empire. Bill Brown established a big horse-trade ranch near Wagontire in the 1890s, taking advantage of the herds of wild mustangs. Although horse prices remained low for much of Brown’s career, he allegedly later made a fortune selling them to the Allied armies during World War I.

The subjects of early livestock kingdom in the High Desert were largely young, single, white males, many of them itinerant and seasonal workers. Schoolteachers in the region's widely scattered communities remained largely male until the closing decade of the nineteenth century. Ranch wives and daughters made up part of the population—particularly in the more densely settled range country of Lake County—but female residents were comparatively few. Peter French built a comfortable ranch house for his new wife, Ella Glenn French, but the city-bred Ella apparently left the P Ranch for Oakland, California, after only a very few short visits and never returned.

Henry Miller and Charles Lux hired a number of fellow Germans as ranch foremen and to work in senior positions, and a few stayed in Oregon after the Miller and Lux empire broke up in the early 1900s. The operation's Pacific Live Stock Company exclusively hired Chinese men as cooks and ranch house domestics.

Unlike the overbearing Pete French, who was gunned down in 1897 by a settler over a water dispute, Californio foreman Chino Berdugo lived long enough to become one of Harney County’s most respected citizens. Vaqueros like Berdugo had a lasting influence on the ranching culture of the entire interstate region, introducing characteristic methods of working cattle as well as distinctive outfits--including saddles, ropes, and clothing--to the southwest corner of Idaho, southeastern Oregon, and northernmost Nevada, known as the ION. During subsequent years, the numbers of Latino ranch employees dwindled throughout the region. Berdugo was among the very few early who remained into the twentieth century. His friendly assistance to the Catlow Valley’s dry-farm homesteaders after 1910 led them to name a small, short-lived community for him. Many of the vaqueros’ work methods and language endured, and the term vaquero persisted, gradually transformed into “buckaroo.”

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

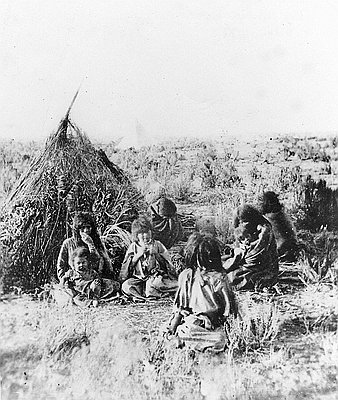

Family of Bannock Indians, 1872

This photograph shows a family of Indians, identified by the photographer as Bannocks, sitting in front of a small pole-and-thatch lodge. It was taken in Idaho Territory in …

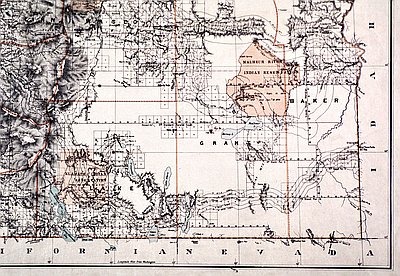

Malheur Indian Reservation

This detail from an 1879 General Land Office map shows the Malheur Indian Reservation in southeastern Oregon. An 1872 executive order by President Ulysses S. Grant established the …

Fort Bidwell

Fort Bidwell in Northeastern California (Surprise Valley), built in 1863 and seen here in 1877, was a secure site for white settlers traveling along the Applegate and Lassen …