From Treaty to Termination

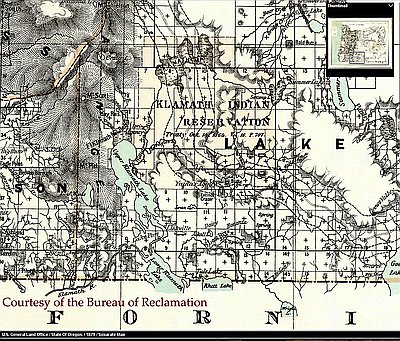

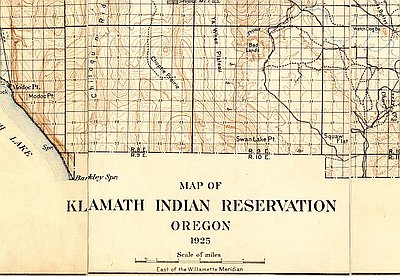

The boundaries of the Klamath Indian Reservation have been disputed ever since the Treaty of 1864 reserved lands for the tribes in exchange for more than 20 million acres of traditional territories. According to former Tribal Chairman Jeff Mitchell, the boundaries named in the treaty encompass 2 million acres. The subsequent survey, whether deliberately or by mistake, cut that to 1.1 million acres.

Klamath representatives challenged the survey. That dispute, plus another over a land trade that Congress authorized the reservation to make with a timber company in 1900 kept the reservation boundaries undefined until a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1938.

The controversies worked in the Klamath Tribes’ favor after the Dawes Act of 1887 divided their reservation into parcels. These allotments, limited to 160 acres per individual, took about a third of the reserved lands. Although the Act authorized the distribution of non-allotted lands to settlers, the surplus, exceeding 800,000 acres, remained tribal territory since the boundaries of the reservation were in litigation.

These lands became extremely valuable. After the Southern Pacific Railroad built tracks through the reservation in 1910, timber companies bought pine trees from its forests, logged them, and brought them to mills and box factories. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sold Indian timber at low prices, driving up profits and boosting prosperity in Klamath County.

Even so, per capita payments for forest revenues made Klamath Indians rich compared to other American Indians. (Only members of Oklahoma tribes that received revenues for oil had more income.) These payments also compensated the BIA for services the Treaty obliged the government to provide. Yet the agency did not permit tribal members to market their own goods or develop their economy by building a mill and other tribal businesses. Many Indians failed to educate themselves; many succumbed to apathy and alcohol.

Tribal leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., to protest federal restrictions on their activities. Their complaints did not fall on deaf ears; these protests were turned against them. Oregon politicians, including Governor Douglas McKay, who became Dwight Eisenhower’s Secretary of the Interior, pushed forward a national policy to liquidate all reservation lands. Terminated by Congress in 1954, the Klamaths lost their country and became one of the nation’s poorest tribes.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

News Article, Klamath Indians Draw Spotlight

This newspaper article describes some of the early debates over the termination of southern Oregon’s Klamath Tribes. The complex politicking reported in this piece went on until 1954, …

Klamath Tribal Council, 1955

To some Klamath Tribal members, which included Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Indians, the reservation symbolized subservience to Anglo-American society, and for greater than 70 years, the reservation had …

Klamath Indian Reservation

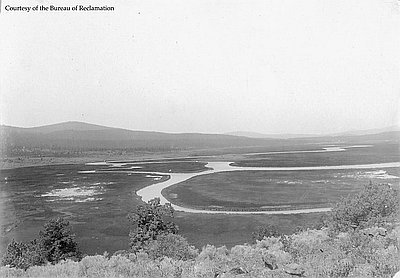

When white explorers entered the Klamath Basin in the 1820s, the Klamath Indians occupied the Upper Klamath Lake area, which included Klamath Marsh and the Sprague and Williamson …