Post-War Population and the Building Boom

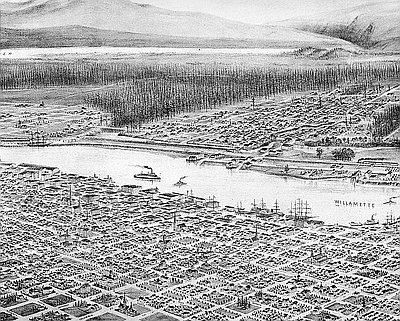

A large number of wartime workers who had migrated to Oregon remained afterwards; Portland’s population escalated from 305,000 in 1940 to 374,000 ten years later. The workers often had come from the South and Midwest, and many of them were African American. Some of the wartime industries adapted to postwar markets, and aluminum manufacturing and the production of civilian aircraft parts remained active and growing businesses. The workers who stayed in Portland after the war strained the city’s housing, and African Americans put pressure on the real-estate and housing trades to deal with racial housing issues such as restrictive covenants and the de facto segregation enforced by bank lending guidelines and red-lining.

As conditions adjusted and a period of economic prosperity replaced one of austerity and sacrifice, construction blossomed in several arenas. One arena was Portland’s traditional downtown retail and office core. Another was Portland’s suburban fringe, in new communities such as Cedar Hills and Somerset West and in the explosive growth in and near once-small towns such as Milwaukie, Beaverton, Lake Oswego, and Gresham.

Construction had virtually ceased in Portland’s central business district during the 1930s. The signal that both the Depression and wartime austerity were over was the construction of the Equitable Building in 1948, a revolutionary structure designed by Pietro Belluschi. The Equitable was a steel framework to which the building’s “skin” of glass and aluminum was attached. It was the nation’s first major building with an aluminum exterior; the first with double-glazed, sealed windows; the first to be fully air conditioned; the first to employ a heat pump for heating and cooling. From architect Belluschi, a master at innovative forms and designs in native Oregon wood, came a startling and elegant introduction of the new International style, using materials that were internationally sourced. The aluminum may have been manufactured in Oregon, thanks to the new hydroelectric-powered aluminum factories, but the Equitable Building was anything but regional in its design or materials.

Elsewhere in Oregon, postwar prosperity boomed the population and suburban development of mid-size cities such as Salem, Klamath Falls, and Eugene. College towns welcomed students supported by the GI Bill, and new suburban residential and shopping developments emerged at the edges of many towns and cities. Whole communities mushroomed in fields that once grew strawberries and nursery stock. The emerging pattern was for a single developer to plat and build the streets, build and landscape the houses, and sell the property. Houses in Cedar Hills, west of Portland, were single-level frame ramblers with picture windows on large lots facing gently winding streets or cul-de-sacs. They were, of course, made of Oregon-milled Douglas fir and cedar, but so were thousands of houses in subdivisions that were thousands of miles from Oregon.

One major postwar development, the shopping center, made a notable Oregon appearance. Lloyd Center, opened in 1960, was among the nation’s first covered pedestrian malls and was the largest mall of its time. But perhaps its major distinction was its location in the center of the older city and within sight of the downtown core, rather than in suburbia. Its success ironically pointed toward Portland’s efforts later in the century to establish itself as a center for the “new urbanism,” and Lloyd Center today is envisioned by planners as a cross-river extension of the original downtown core.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

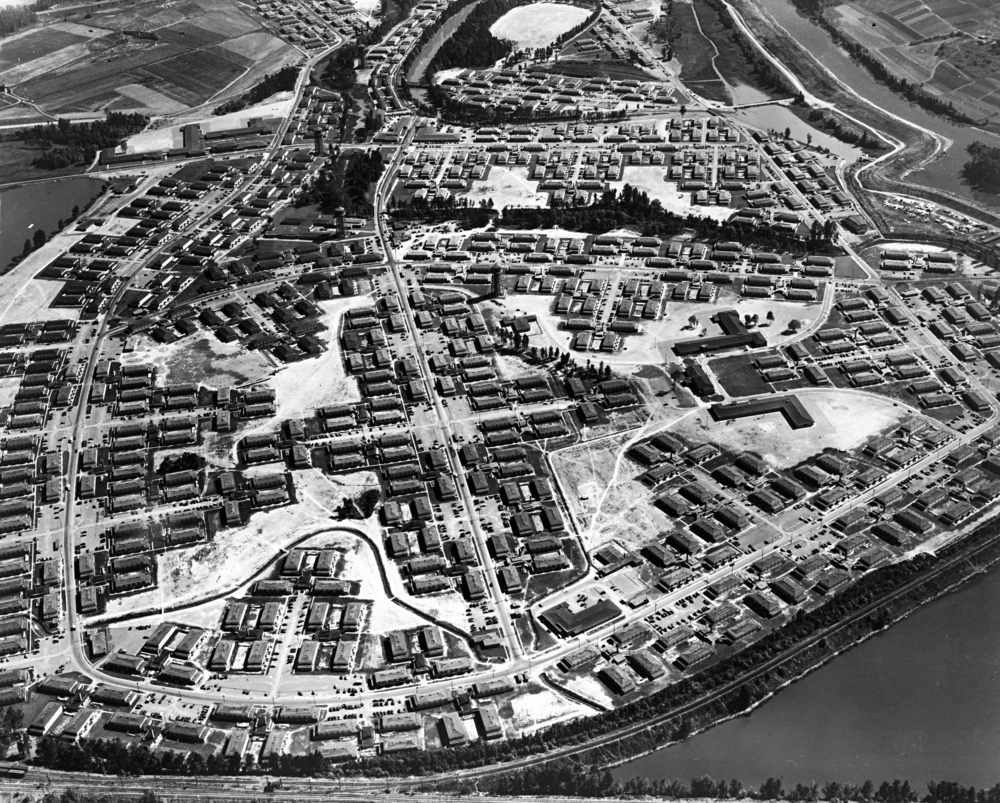

Vanport Residences, 1947

Built to address Portland’s World War II housing shortage, Vanport was called “The Miracle City.” Over 72,000 new workers arrived in Portland during the war. Industrialist, Henry J. Kaiser, imported so …

Somerset West, 1963

This aerial photograph shows the first five model houses at the grand opening of Somerset West, “planned $500 million ‘satellite city’ 10 miles west of Portland,” according to …

Kaiser & Oregon Shipyards

In 1940, Henry J. Kaiser signed an agreement with the British government to build 31 cargo ships to aid that country in their war effort. After scouting several …