- Catalog No. —

- Samuel R. Thurston papers, Mss 161

- Date —

- June 22, 1850

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Black History, Government, Law, and Politics, Oregon Trail and Resettlement, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Research Library

- Regions —

- Willamette Basin

- Author —

- Samuel R. Thurston

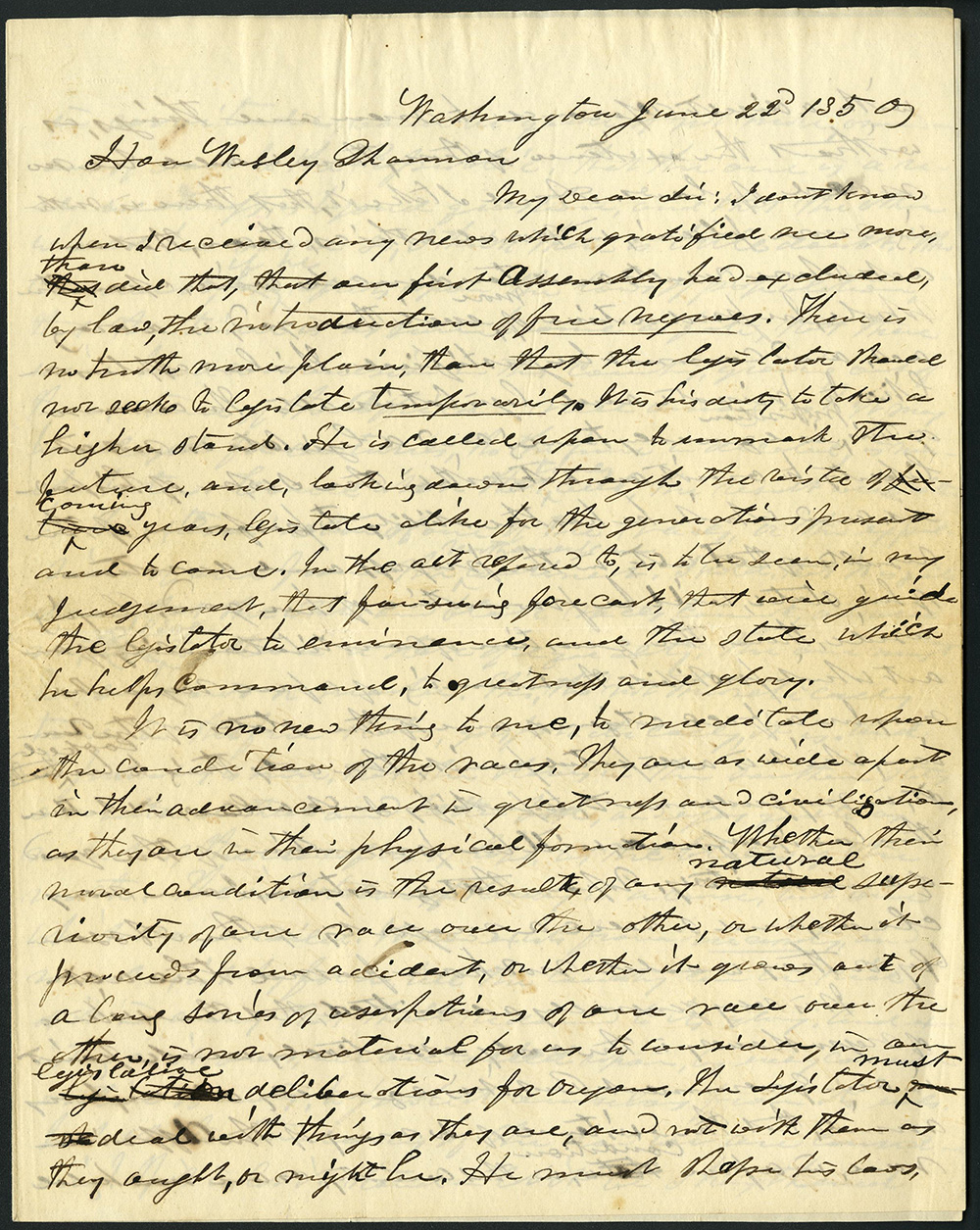

Letter from Samuel R. Thurston to Wesley Shannon, June 22, 1850, regarding Oregon's Black exclusion laws

This letter was written by Territorial Representative Samuel Thurston in 1850 to his friend and political ally Wesley Shannon, a member of the Oregon Territorial Legislature. Thurston was in Washington, D.C., to help write and pass what would become the Oregon Donation Land Law; but as this letter reveals, he was also preoccupied with what was happening back home, as his colleagues grappled with two of the most important issues of the nineteenth century: slavery and race.

Oregon’s Provisional Government passed anti-slavery and Black exclusion laws beginning in the early 1840s, a reflection of the desires of a predominantly white settler population who opposed slavery but feared living in a free state that was open to Blacks. Some of that fear was political—the status of free Blacks and formerly enslaved people in the U.S. dominated congressional debates, directly affecting the admission of new states to the Union. Oregon desperately wanted to be of that number, and local legislators believed that passing both anti-slavery and exclusion laws would extricate the territory from the heat of the conflict. Many Oregonians also considered themselves so-called Free Soilers, who opposed an enslaved labor force competing with free white men.

Most significantly, white settlers had brought with them to Oregon Country the stark racism of the perceived biological and cultural superiority of one race over all others—what we now identify as white supremacy. This worldview has permeated every discussion about race in American history.

Thurston begins his letter supporting yet another Black exclusion law, passed by territorial delegates in 1849, and he follows his praise with a primer on prominent, and popular, nineteenth-century theories that justified the enslavement of human beings and the continuing subjugation of free Blacks:

- The “evils” that are greater than slavery: “…the existence of negro slavery is the only essentially weak point in our government. But it is equally clear, to my mind, that the existence of so many of the African race, in a free condition, in this country, as are now held in servitude, would be quite, if not more, ominous of evil to the Republic.”

- The inevitability of violence: “Who can doubt, if he reflects upon the laws of population, that the time is as sure to come as fate, that there will be a convulsion in the country, growing out of the existence of the African race among us?...Come when that time will, the result will either be the extermination of one of the races, or the expulsion of one from the North American continent. I hold, that is quite clear, that the white and black races cannot, will not, live together in a state of equality. The one must be the servant or master.”

- The protection and comforts of enslavement: “And it probably is true, that the slaves in the southern states are better clothed, and better fed, and enjoy quite as much of the comforts of life, as the blacks of the north.”

- The degradation of the white race in the face of “surplus” populations of freed slaves: “No man can fail to see, that the south must have some outlet for the surplus & refuse population of her slaves, and so long as the gateways are open, this surplus, that refuse and blight-bearing hord [sic] will be turned over to us, to fill our alms houses, and degrade our honored and sturdy yeomanry.”

- The “natural” end of slavery: “But if that outlet [immigration to free states] is closed, by the stern sentinels of the law, executed by a free people tenacious of their rights, and watchful of the good of their state, slavery will work out its own destiny.”

- The threat to white labor: “His presence beside our freemen, will bring a stigma upon free labor, for it is well known what an influence association has upon the human mind. Let us then…exclude this race from among us, and build up a community where labor shall not be associated with negros, and where, to plough the field, shall be an honor to the white man who ploughs it.

By the time Thurston was writing to Shannon, the abolitionist movement had gained a foothold in political and religious discourse, so Thurston was well aware of the moral debate that contradicted his suppositions. For example, he acknowledges the possible unconstitutionality of an act “which prohibits the incoming of a free negro who may be a free citizen,” but he “lays it aside” by labeling the point “disputed” and declaring that the law must pass to protect Oregonians from the perceived chaos of a multiracial society. Thurston takes care to use words such as “duty,” “freedom,” “greatness,” “good,” and “honor” to describe his motivations, and “ominous,” “evil,” “wretched,” and “blight” to describe Black immigration.

The other rhetorical device Thurston relies on is the use of declarative statements of “fact” with an appeal to innate reason or consensus. “And I take it, there is nothing more plain, in moral ethics," he writes, "than, that an act whose results and tendencies will, upon the whole, be productive of more evil than good, is a wrong act, and cannot be justified.” He continues: “That the one [slavery] is a real weakness, is beyond question, and that the other [abolition of slavery] would be more so, I think there is little doubt.” Then: “I hold, that it is quite clear, that the white and black races cannot, and will not, live together in a state of equality.” (Emphasis added).

It is likely that Thurston intended this letter to be shared with others, perhaps even publicly. He was a lawyer, so it is no surprise that he at times measures duty in terms of liability. For example, the abdication of responsibility for the enslavement of Black people by white people takes in this letter a form of indifference. “The institution of slavery is a curse, but one which was entailed,” he writes, characterizing the torture and murder of African Americans as a mere inheritance that his generation must grudgingly maintain. Conveniently, his “duty” as a legislator aligned with his economic interests: he insisted on keeping “white” in the Donation Land Law, which allowed him, and those who looked like him, to claim most of the free land in Oregon. (Thurston would not see his hard work come to fruition, however; he caught yellow fever on the trip home to Oregon in 1851 and died on the ship.)

Thurston’s parting attempt in the letter to elevate his posterity in Oregon history is particularly poignant: “If you can read these hastily scribbled lines, you will learn my opinion of the law, let that law, in honor of its enactors, go down in the archives of the state, and when Africans and African slavery, shall have left our shores, and the former shall be flourishing, if flourish they ever do, in their own country, let that law remain as a proud reminiscence of its making.” Oregon’s exclusion laws, of course, did not “protect” white Americans from the moral implications of enslavement and elevate its citizens to "greatness"; rather, they implicated the government and its people in a legacy of white supremacy that has extended into the twenty-first century. One of Thurston’s proudest moments is also one of Oregon’s most shameful.

Further Reading:

Nokes, R Gregory. Breaking Chains: Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

Mahoney, Barbara. The Salem Clique: Oregon’s Founding Brothers, Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2017.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Promise: The Oregon Story, 1800-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Written by A. E. Platt, © Oregon Historical Society 2021

Related Historical Records

-

Debate Over Oregon Constitution

This document is an excerpt from a speech by Missouri congressman John B. Clarke in the U.S. House of Representatives supporting the admission of Oregon. He outlines the main objections …

-

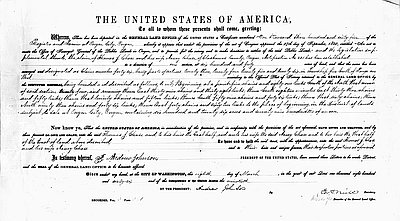

Oregon Land Donation Claim Notification

This image shows a certificate issued March 8, 1866, that grants 640 acres of land in Clackamas County to Thomas J. Chase and his wife, Nancy. The document …

-

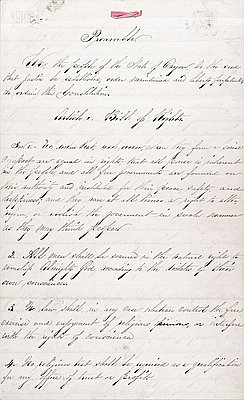

Draft of Oregon State Constitution

This document is a draft version of the Oregon State Constitution’s preamble and bill of rights. It was written in 1857. After defeating motions to organize a state constitutional convention …