White Family Fishermen, Skill, and Masculinity

Finnish Socialist Club Picnic, Astoria, 1922 Finnish Socialist Club Picnic, Astoria, 1922

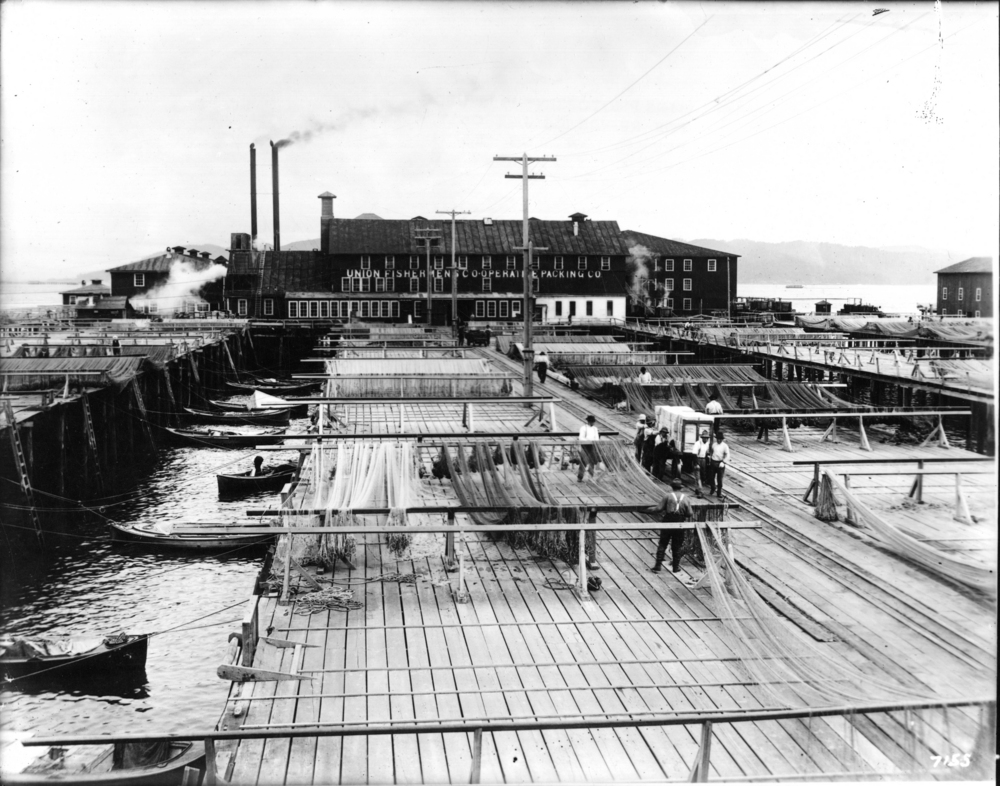

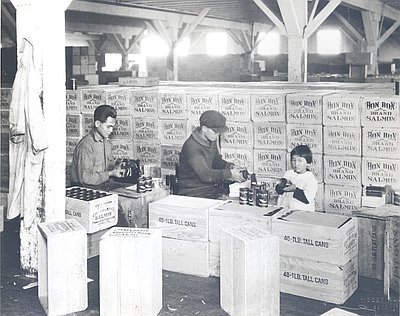

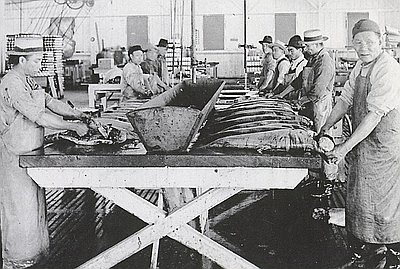

The earliest commercial fishers for the canned-salmon industry on the Columbia River were the small circle of cannery operators, their families, and friends; but this rapidly expanded into fishing crews whose ethnic and class backgrounds were remarkably different from those of the first owner-operators. By the mid-1870s, larger corporate interests had established plants on the river and recruited Italian men from the San Francisco Bay Area in a seasonal work migration to fish for them. One 1882 appraisal of the salmon fisheries taken from Irene Martin’s Traders’ Tales explained: “Only white men engage in fishing, the greater proportion, however, being Italians, Fins [sic] and other foreigners, men without families, who come to the river from San Francisco only during the fishing season.”

These largely male crews were a rough and tumble lot. Violence among the workers and with others was common, especially in Astoria. As historians Adele Perry and David Peterson del Mar note, violence in the Pacific Northwest’s nearly all-male, or “homosocial,” society based on resource extraction served to secure the power of the colonizing interests—national and commercial—because the violence assured white men a place atop the social hierarchy.

Illustrating that assertion of power, in the 1880s Euro-American fishermen used the threat of violence to keep Chinese men off the boats. According to contemporary observers, quoted in David Jordan and Charles Gilbert’s 1887 report on salmon fishing and canning interests, there was: “[N]o law regulating the matter, but public opinion is so strong in relation to it, and there is such a prejudice against the Chinamen, that any attempt on their part to engage in salmon fishing would meet with a summary and probably fatal retaliation. The 1886 founding of the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union (CRFPU) was in part an institutionalization of these threats of violence.

While union dominance allowed Euro-American fishermen to exert much influence in the industry, their ethnic and national backgrounds left many suspect in terms of their “whiteness” and, as a consequence, their manhood as well. To lay claim to both categories, they explicitly embraced a particular notion of manliness. Early in its existence, the CRFPU launched a campaign to assert a new identity of its members as family men vested in civilizing the region. In one 1890 publication, the union explained that a large proportion of its members were either “permanent residents of the city of Astoria,” implicitly comparing them to transient Italian and Chinese workers. The remainder, the union claimed, were spread out along the banks of the Columbia and “when not fishing a great many of them are engaged in clearing up their land and making other improvements, as a majority of them are real, live home builders in the fullest sense of the word.”

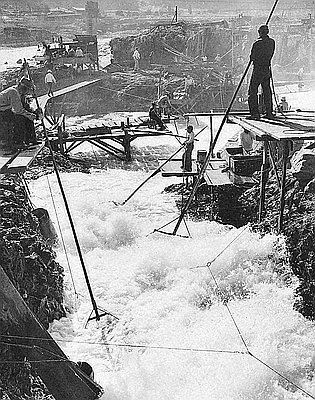

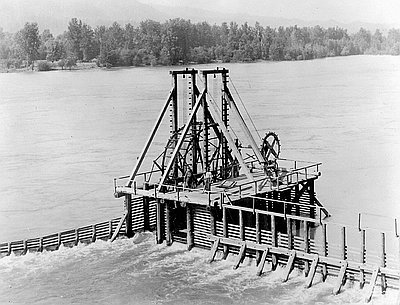

To emphasize the point, the labor bulletin explained that “45% are married and have families.” These “hardy sons of Vikings and Norsemen” were “moral, sober and industrious.” The pamphlet emphasized that Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, and Austrian union members brought a “general advancement” to Astoria, claiming that “a mighty moral uplifting has taken place.” The unionists were “a higher and nobler type of manhood than ever before in the annals of this industry.” Union fishermen were able to make this vision “stick,” and twentieth-century battles surrounding different fishing technologies and salmon conservation hinged, to some degree, on these notions of gillnetters as deserving family men harmed by fish traps and fishwheels.

Immigrant handbooks, like those in Finnish, played on ideas regarding this “higher and nobler type of manhood” and introduced the region to prospective immigrants as “the good life” with “comfortable” family homes. Once in Oregon, Finns especially organized their political and social life around the construction of these gendered ideas of family.

Fishermen’s identities were also tied to the work itself. Many Euro-American migrants to the region had come from fishing areas in Europe and North America, and they brought with them ideas about men as fishers. In the nineteenth century, when fishers’ boats used sail power, one mark of masculinity was the claim to high levels of skill that would allow a man to make more runs in a night and haul more fish than those with lesser abilities. Local family lore told of grandfathers who were “renowned” for their gillnet sailing abilities. New technology eventually eliminated the days of sail, but fishers held onto their navigational and boat-handling skills, and the physical demands of the work as a measure of masculinity.

As resident family fishermen became the norm on the Columbia, fathers passed fishing lore and practices to their sons and nephews. Hank Ramvick remembered: “I started going with my dad out in gillnet boats…before I could walk….I just evolved into a fisherman…and that’s the way it was with most of the kids I grew up with…whose fathers were fishermen.” Cecil Moberg remembered that even if young boys did not fish on the boats, they could pick up odd jobs helping with nets or cleaning boats—work that passed along fishing knowledge to subsequent generations.

For gillnetters on the lower Columbia, the CRFPU embodied many of the notions of masculinity held by fishers. From the perspective of those unionists, fish prices were the most important factor on the river, and they insisted that their wives and daughters support their efforts even when those were at odds with the demands of cannery workers, reinforcing patriarchy at home and in the industry. Being a good unionist could also bring together ethnic and masculine ideals. Recounting the 1952 strike, a Greek fisherman at Clifton, Washington, explained: “There is no word for scab in the Greek language because no Greek ever scabbed!” Ethnic and national pride was built on the notion that honorable men did not “scab.”

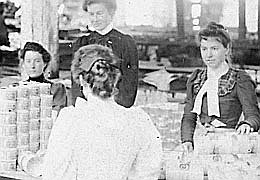

On the Columbia River, the work culture of Euro-American fishermen evolved from the rough, violent masculinity of seasonal labor to one dominated by ethnic patriarchy that emphasized fishing as the principal work for family breadwinners. As a consequence, those fishers made the river a white, male domain. Still, women played important if unrecognized roles as bookkeepers, parts runners, and general hands. By the 1970s, changes in technology that allowed for easier handling of the nets and altered social expectations regarding women’s work combined to create a few openings for women on the boats, but by that time the commercial fisheries had dramatically declined in scope.

© Chris Friday, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.