An Ethnically Divided Workforce

Given the intense hostility toward Asians in the West, it is not surprising that of the immigrant groups who were active in the salmon canning industry, the Chinese are most frequently labeled by ethnicity in the documents accompanying this essay (Native Americans are also consistently labeled, and a separate essay focuses on that experience). Chinese were easily identifiable as outsiders during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Chinese immigrants were the most visible nonwhite group in Oregon until about 1920, outnumbering Japanese immigrants in the 1910 census, 7,616 to 4,280.

As in the other western states, Chinese, and later Japanese, immigrants to Oregon and Washington faced hostility that increased as their numbers grew, resulting in a variety of federal, state, and local restrictions on them. Although many spent decades as sojourners or lived out their lives in the Pacific Northwest, they were barred from naturalization, from marrying Euro-Americans, and, by the 1920s, from owning land. They were permanent outsiders, defined as racially, biologically, and immutably different.

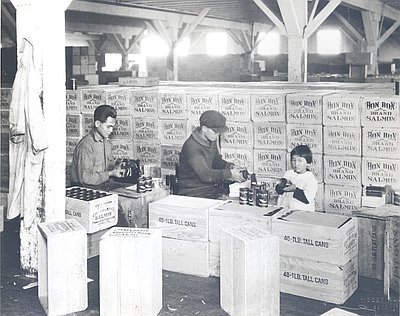

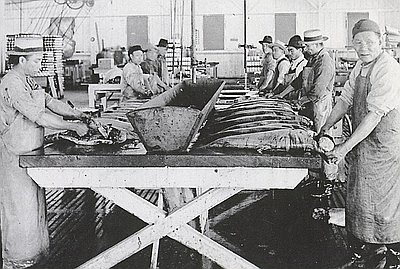

Given this status, it is not surprising that the documents present clear evidence that the Chinese experienced segregation in Columbia River salmon canneries. Workplace segregation is visible in “Chinese Workers Prepare Salmon for Canning” and “Chinese Workers in Astoria Cannery.” In both photographs, Chinese men are doing work that was deemed suitable for them (and later for women) but not for white men. Cleaning, chopping, and canning salmon were so associated with Chinese workers that when the work was mechanized, the machines were dubbed “Iron Chinks.” Although some jobs within the industry were deemed Chinese work, others were reserved for whites. While documents like the 1894 U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries report demonstrate that the canneries sometimes purchased fish from Native Americans, especially in the industry’s infancy, fishing increasingly became “white” work.

Such workplace segregation was not simply a matter of giving the lowest status, worst paid, or least skilled work to the group that was lowest in the pecking order. Rather, it was justified by the belief, common throughout nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America, that biological differences made certain ethnic/racial groups better suited to particular types of work. As early as 1872, George Hume apparently brought the first Chinese workers to his cannery. As this language suggests, cannery owners sought out Chinese workers, whom the Weekly Astorian considered the “chief reliable form of help” for these jobs, some of which required considerable skill.

The contract between Seid Chuck and the Seufert Brothers Company in The Dalles, dating from 1908, provides vivid evidence of this. At the time of the 1900 census, no Chinese lived in The Dalles or in all of Wasco County. By 1910, there were still only fifty-four Chinese immigrants in The Dalles. These numbers explain why, if Seufert believed that Chinese workers were best for cannery work, he had to hire labor contractor Seid Chuck to provide them: there simply was not a sizable pool of eligible Chinese workers in The Dalles. It is interesting that, when the fishermen of Astoria established a cooperative that ran a cannery, they, too, employed mostly Chinese workers for these jobs.

Typically, workplace segregation was linked to a two-tier wage system, and “white man’s work” was generally tied to better wages. An 1888 federal study “found that Chinese cannery laborers made an average of $40 to $50 per month,” a wage comparable to that of a gillnetter. Similarly, a member of the Seufert family asserted that their company paid the same wages to Chinese and whites and that “Chinese cannery labor was not cheap labor.” The contract between Seid Chuck and Seufert Brothers shows that Chinese laborers were hired for a variety of jobs at different skill levels within the canneries, each paid at a different rate. These workers could earn between $240 and $360 for an eight-month season, or $30 to $45 per month, in addition to an allowance for food. Without the salary figures for the various jobs held by white men, it is not possible to determine from the related documents whether Seufert's claim was accurate.

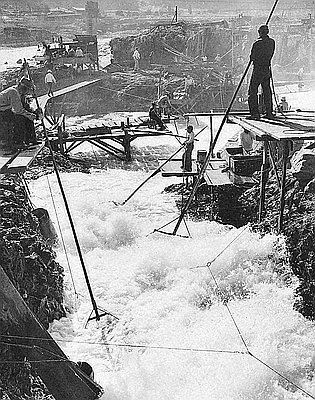

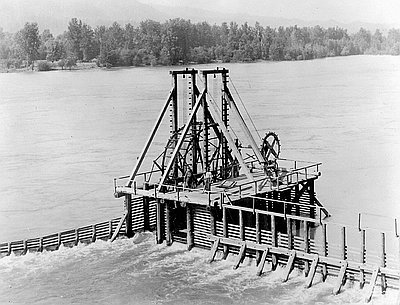

Even if the white fishwheel and fish house workers employed by Seufert Brothers did not earn a higher wage than the company’s Chinese cannery workers, it seems likely that the independent fishermen who supplied salmon to the Astoria canneries did. There, as the documents on the 1896 strike attest, unionized fishermen were able to bargain collectively for a price and had the muscle to prevent others from encroaching on their catch. In the wake of the strike, they established their own cooperative cannery that enabled them to control production. As independent fishermen and as members of a cooperative, they were able to exercise control over their work hours and conditions.

Chinese men, who did not have access to fishing jobs and who were excluded from the fisherman’s union (as they were from virtually all unions in the West), did not have the same clout. For example, the contract with Seufert mandated that they not only work an eleven-hour day, six days a week, but that they also put in extra hours during the week and on Sunday, when needed. The photos suggest the difficulty of the conditions: certainly gutting hundreds or thousands of fish in a crowded factory for long hours could not be considered pleasant work.

Chris Friday’s Organizing Asian American Labor demonstrates that Chinese and other Asian workers were not merely the “cogs in the wheel” of the industry and that they were able to shape their working conditions and empower themselves to some degree. He argues that seasonal rates, like those shown in the Seufert contract, resulted from a struggle by Chinese workers against an earlier, day-rate system. Yet, evidence of Chinese protest and empowerment are not discernible in these documents. While Seid Chuck’s ability to supply Chinese labor gave him the power to negotiate with the Seufert Brothers, he negotiated as a labor contractor rather than as a union representative. Although it is possible that Seid Chuck was concerned about his workers and their working conditions, his primary interest was his own bottom line: he was paid to supply workers, not to advocate for them.

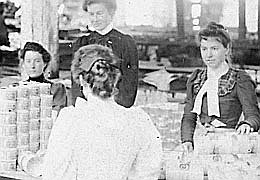

While Chinese workers appear in the documents as cannery workers, Euro-Americans appear primarily as cannery owners and fishermen. It is suggestive that European immigrants and Americans of European ancestry are much less consistently identified by ethnicity than are the Chinese. At times, as in the case of the photograph of the Finnish Socialist Club, European immigrants were labeled—and self-identified—as an ethnic group. In other cases, people of European ancestry are simply “white,” or not given a racial/ethnic tag at all. In the photograph of women cannery workers, for example, the apparently Euro-American women are identified by gender but not by ethnicity.

Such inconsistency in the labeling of Euro-Americans is evident both in the interpretive text of the related documents and in the documents themselves, and it speaks directly to the issue of inclusion and exclusion. For many Euro-Americans—including many immigrants—inclusion came rapidly in the West, where nineteenth-century immigrants were entering a new society and were participants in the building of that society. As immigrant and second-generation Euro-Americans, including those from groups that were not readily accepted in the East, arrived in the Pacific Northwest and were pioneers in industries like salmon canning, they established themselves as founders, as Pacific Northwesterners, and as whites. This rapid entry into society helps account for the frequent absence of ethnic labels denoting difference among Euro-Americans.

Owners of canneries, like the Seuferts, are not marked as ethnics in the documents, although many were first- or second-generation Americans. The Seuferts, for example, appear on the 1900 census as second-generation German Americans: Frank Seufert of The Dalles was born in New York to German parents, and his wife Annie was a New Yorker born to Prussian parents. Yet, while the Seuferts appear several times in these documents, they are never identified as German Americans. Similarly, U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries Marshall McDonald refers to "Indians" in his 1894 report but provides no ethnic label for the Meyers Brothers, whose name suggests German origins and who appear in the 1900 census as immigrants from Canada.

A person did not have to be a company owner to be included as part of the white citizenry. Even Euro-American cannery workers are either not labeled at all or are identified as “white.” Thus, the document comparing the wages of Chinese cannery workers to other workers identifies those other workers as “white.” Yet, an examination of cannery towns demonstrates that there were many European ethnics among these undifferentiated white American workers. In The Dalles, for example, where the Seuferts operated, first- and second-generation Germans made up over 10 percent of the population. Among the 197 white residents of Meyers Falls (later Kettle Falls) who were over twenty years old in 1900, a third were foreign born. While no ethnicity is noted for the “white” women labeling cans at Megler Cannery in Brookfield, Washington, the census shows that in 1901 there were likely many first- and second-generation immigrants among them: of the fifty adult women in Brookfield in 1900, eighteen were foreign born and nine were second-generation immigrants.

Although these inland river towns appear to have been populated mostly by native-born Americans, European immigrants and their children made up a substantial minority. Their role as settlers and as Euro-Americans in a setting where the most prominent “others” were Native Americans (sometime represented on cannery labels as authentic and exoticized Americans) and Asians led to their inclusion as part of white society. Their acceptance was also helped because the bulk of these immigrants hailed from northern European countries like Germany and Scandinavia, they were fair skinned, and they were often both Protestant and literate.

© Ellen Eisenberg, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Finnish Socialist Club Picnic, Astoria, 1922

This photograph shows members of the Finnish Socialist Club picnicking in Astoria in 1922. The Finnish Socialist Club was one of Astoria’s most prominent ethnic organizations during the …

Chinese Workers in Astoria Cannery

This undated photograph of the interior of an Astoria cannery is from the Burlington Northern / Spokane Portland and Seattle Railroad Collection. This promotional photograph conveys the message …

Chinese Cannery Workers near Astoria, Oregon

This stereographic image, printed by the Keystone View Company, has this description of the fish-cleaning process written on the back: “One [person] does nothing but cut off heads, tails, …