Eastern Oregon

Eastern Oregon is bounded north-south by the Wallowa Mountains and the Alvord Desert, and east-west by the Snake River Valley and the Ochoco National Forest. The region’s ten counties are home to a range of peoples, including the Nez Perce, Burns Paiute, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla Indians; Hispanic communities from Milton-Freewater to Nyssa; descendants of Chinese and Japanese settlers from John Day to Ontario; and Europeans from the Scotch in Althena to the Basques in Jordan Valley. At the Oregon-Idaho state line, the Four Rivers Cultural Center in Ontario celebrates the confluence of these diverse worlds.

Like the rivers that sustain this region—the Snake, Malheur, Owyhee, and Payette—varied cultures flow from different sources. Since 1910, the annual Pendleton Round-Up has drawn cowboys and cowgirls, ropers, riders, and tourists for three days of saddle-bronc riding, calf roping, bareback riding, steer wrestling, and the Happy Canyon pageant. Cowboy culture thrives in the Round-up’s events and material arts. A visitor might encounter the work of the Severe Brothers Saddlery. Duff Severe, who died in 2004 at the age of eighty-four, received a National Heritage Award for his artistry in making utilitarian and miniature saddles. He and his brother, who have saddles in the Smithsonian Institution collection, bequeathed their skills to sons and nephews who run the saddlery.

Historically, the Pendleton Round-Up has brought European and indigenous people together. The September date both allowed grain farmers to complete their harvest and built on an indigenous tradition of fall reunion. Today, Native American communities gather in a temporary teepee village near the rodeo grounds, selling frybread, traditional jewelry, and beaded baseball caps. As festivals everywhere do, Round-Up engenders a “time out of time” feeling, as normal social boundaries break down and strangers greet one another on the street. Yet, this event also reveals fissures in the social fabric. The Happy Canyon pageant is a western saga of battles between white settlers and Native people, but each group relates the tale with their own view of history. The narratives any community creates are mythic—not false, but partial in their explanation of origins or interpretation of events.

At the Umatilla Reservation in Pendleton, home to the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla, exhibits look at Indian-white relations. The treaty of 1855 with the U.S. government strictly circumscribed the homeland the tribes call “Nicht-yow-way.” In 2005–2006, the tribes shared with visitors an indigenous view of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with a “treaty drama” and other programs at the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute. A permanent exhibit, “Who We Were, Who We Are, Who We Will Be,” recounts the story of precontact culture, the arrival of white settlers, and visions of the future. Tamástslikt also features the work of Native artists such as Maynard White Owl Lavadour, a Cayuse/Nez Perce artist who earned a Governor’s Arts Award in 1997. Lavadour learned to bead and make cradleboards from his great-grandmother Susie Williams and his grandmother Eva Williams Lavadour.

Highway 82 from La Grande winds through the canyons and valleys between the Umatilla and Wallowa Whitman national forests, alongside and crossed by a series of officially designated wild and scenic rivers in the Grande Ronde Basin: Joseph Creek and the Wallowa, Minam, Lostine, and Wenaha. Punctuating the landscape are small communities of farmers and ranchers, as well as traditional and contemporary artists. The towns of Enterprise and Joseph support thriving sculpture foundries established during the 1990s. Alongside bronze renderings of western life, the work of folk artists appears in shows throughout eastern Oregon. Harold McLaughlin of Enterprise retired from farming at age eighty-six and built wooden tables and picture frames from salvaged lumber. Hope McLaughlin made traditional quilts, sometimes ten to twelve a year, as well as hooked and woven rag rugs. She used traditional designs, with occasional forays into political symbolism such as American flags during the Gulf War. Folk arts preserve traditions, but individuals innovate in their use and function.

Chief Joseph Days in July honors the Nez Perce chief and his legacy. Festivals celebrate but also commemorate, often incorporating a complex history. Joseph’s history includes the forced expulsion of several Nez Perce bands from their ancestral lands, culminating in their pursuit by federal troops in 1877 to just south of the Canada-U.S. border. Chief Joseph Days also create what anthropologist Victor Turner called “communitas”—a communal spirit found at festivals, in pilgrimage, and other events where group solidarity transcends deep divides.

During the gold rush of the 1860s, immigrants brought cattle and sheep to the region, shaping its economy and culture. As new groups arrived, divisions emerged between whites, Native people, and the Chinese who settled in John Day, Canyon City, and Baker City. Today, traditions associated with these early days fuel tourism. In John Day, remnants linger of an era in which thousands of Chinese followed the gold rush to eastern Oregon. The papers and objects of Ing “Doc” Hay, an herbalist and owner of the Kam Wah Chung Company, offer a glimpse of the late nineteenth century: letters, diaries, Buddhist statuary, and texts of Chinese operas.

Japanese and Japanese Americans hold an important place in Oregon history. Answering a call for immigrant labor, Asian workers came to the Pacific Northwest in the 1880s. After the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act prevented further immigration of Chinese, railroads recruited laborers from Hawai’i and Japan. In the 1900s, new irrigation projects expanded sugar beet production in eastern Oregon. Issei, first-generation immigrants, went to the Snake River Valley, alternating seasonal labor with railroad work. During World War II, when Japanese on the West Coast were forcibly removed and incarcerated, those living in eastern Oregon, western Idaho, and parts of eastern Washington remained free. Signs of their legacy are evident in the Japanese seasonal festivals at the Buddhist temple in Ontario. One central event is the Obon or Bon, a Buddhist festival that originated in China. At home altars, families offer food to ancestors, particularly those recently deceased, who are believed to return during Obon. Such events are reminderes of how differently cultures perceive life and death. The Four Rivers Center also hosts Obon celebrations, bringing the Japanese American community together with the other “rivers” of the region’s cultural heritage. Additionally, the center created a Japanese garden to honor Japanese and Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II and the Japanese Americans who have fought for the United States.

Throughout eastern Oregon, Latino communities also have changed the cultural landscape. In Milton-Freewater, saddlemaker Santos Garcia apprenticed at age six in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. He has been making his own saddles since age fifteen and raised his four sons in his saddlery. In the 2000s, a son stepped forward to run the family shop.

In the late twentieth century, migrants also went to the irrigated sugar beet fields surrounding Nyssa on the Idaho-Oregon state line. Latino residents are long established in this region, tracing their history to the bracero program during World War II. To fill labor shortages, the U.S. and Mexican governments formalized a long-standing migration pattern in 1942. Over the next five years, more than 15,000 braceros worked in Oregon. Though the law ensured minimum wage, health care, room, board, and freedom from discrimination, historian Erasmo Gamboa documents the poor housing, inadequate food, accidents, and racial discrimination many endured.

Folk artist and curandera Eva Castellanoz remembers the words of Fidel Silva, her father and an early bracero. “He always said, ‘I’d rather be a poor man in America than a millionaire in Mexico.’” Silva moved from Guanajuato, Mexico to Pharr, Texas, and finally to Nyssa. Eva followed as a young bride, pregnant with the first of her nine children. While visiting her husband’s family in Guadalajara one year, she watched flower makers on the street dipping paper into hot wax to form coronas, handmade floral crowns. She molds her own coronas for baptisms, weddings, and the quinceañera, a young woman’s fifteenth birthday celebration and coming-of-age ceremony. She also makes lassos for weddings, linked crowns that symbolize a union of two people. In her teachings, Eva uses traditional forms to send a contemporary message about gender and power. Eva also practices as a traditional healer or curandera, attending to the spiritual, psychological, and physical needs of clients. Curanderismo is a complex folk system that incorporates indigenous beliefs and practices, Catholicism, and Spanish medical herbs and concepts.

Mexican celebrations flourish on the streets of eastern Oregon communities. Cinco de Mayo (May 5) marks the 1862 Mexican victory over the French, and Dieciseis de Septiembre (September 16) commemorates independence from Spain in 1810. Through festivals, communities combine myth and history, new and established traditions. One central form is the piñata, a cardboard, crepe paper, and glue creation often shaped like an animal and filled with candies, fruits, and toys. A newer cultural display is the lowrider, a car controlled by a customized hydraulic system that allows it to move side to side as well as up and down, the offspring of Mexican and American cultures in which young men cruise the streets.

Seasonal festivals create a means of giving thanks for natural abundance, merging Christian and indigenous beliefs and practices. Hermiston residents offer gratitude for the harvest on El Dia de la Cosecha (harvest), with an outdoor mass at Our Lady of Angels Catholic Church. Public festivals enact community beliefs and ethnic pride that long-settled Latinos, as well as new immigrants, want to pass on to their children.

Originally from the Pyrenees Mountains bordering Spain and France, Basques arrived in the Jordan Valley area in the late nineteenth century. Men from the mountainous Basque provinces often had limited economic opportunities, particularly younger sons since inheritance customs favored the eldest males. The expanding sheep industry in eastern Oregon and western Idaho needed workers who could withstand the harsh conditions and loneliness of the work. Basques, known for their thrift and discipline, filled that niche, bringing with them traditional foods and culture and a new language. Jim Arritola, a Basque descendent in Malheur County, described the language this way: “The old Basques say that our language was spoken in the Garden of Eden. . . . Others say that even the Devil tried to speak Basque but gave up because it was too difficult.”

Originally shepherds, many Basques now run thriving businesses integrated into the larger community. At festivals, ethnicity can reemerge in a public forum. Basque celebrations such as the September festival in Jordan Valley feature family-style cooking with olive oil and lots of garlic; dances like the jota and porrusalda; muz, a card game; and pelota, a ballgame played on a public court. Women’s traditional dress includes aprons and headscarves; men’s clothing features a wide waist sash and bound pant legs. Visitors can sample foods such as bacalao (dried cod), paella, and tripacalos (tripe in tomato sauce) and watch locals compete in games including weight hoisting, the javelin throw, and a log-chopping competition.

From Mann Lake to below the Nevada state line and from the Idaho-Oregon state line to the Gearhart Mountains, the heart of the Oregon’s southeast is cattle ranching and cowboy culture. Many lament the loss of family farms and ranches and their accompanying cultures, yet 90 percent of the ranches in Harney County are family owned and operated. Buckaroo traditions thrive in small towns like Crane, where rawhide braider Terry Ott has been sought out for his variety of ropes—riatas, hackamores, and quirts.

In Malheur County, Frankie Dougal of Jordan Valley has perfected the art of spinning the horsehair into fidors, hackamores, and snaffle bit trainer ropes. She makes horsehair ropes, a skill learned from her mother, who apprenticed in her own youth to a Mexican vaquero, the cowboys who came north from California and Texas in the nineteenth century. They brought with them an open-range system of cattle herding with roots in sixteenth-century Spain. Their methods live on today, evident in the trade’s names and tools: stirrups, chaps, the lariat or riata, McCarty (mecate), tapaderos, bronc, and rodeo. Ruel Teague of Burns is a musician in Burns, playing for audiences on harmonica, mandolin, guitar, banjo, or fiddle. “I guess I was born with it—it came down the line,” Teague says of his family’s musical legacy.

Another art flourishing in eastern Oregon is cowboy poetry, verse created from working lives. Poets have performed at gatherings in Pendleton, Baker City, Burns, and other regional centers or at the cowboy poetry festival held each January in Elko, Nevada. Folklorists at the Western Folklife Center, which sponsors that event, write that cowboy culture is a “jazz of Irish storytelling, Scottish seafaring and cattle tending, Moorish and Spanish horsemanship, European cavalry traditions, African improvisation and Native American experience, if not oppression.” Men and women cowboy poets live in town as well as on the ranch. Ruby Kirk of Weston has frequently attendee at festival, sharing her poems about life on a ranch. Cowboy poetry, like other folk arts, changes and adapts, surviving because it serves as a vehicle for expressing the indignities and epiphanies of daily life.

The history of the Burns Paiutes exemplifies the tenacity of culture through periods of strife. Descended from the Wadatika Paiute band that once hunted and gathered across what is now southeastern Oregon, the group struggled for a century to reclaim their land. In 1872, the U.S. government created the Malheur Indian Reservation to open more grazing land for white settlers. Almost as soon as the reservation was created, the government began reducing its size—readjusting the boundary in 1872 and again in 1876. Following the Bannock War of 1878, two executive orders (in 1883 and 1889) dispossessed the Paiutes of the rest of their reservation. It was not until 1972, that the descendants of the Paiute band acquired the 771 acres that is now the Burns Paiute Reservation. Minerva Soucie’s baskets reflect how folk arts can preserve deeply held cultural values. In making baskets and gathering traditional foods, she said, “You have a feeling that you’re in touch with your ancestors that have taught you this, that you’re carrying this, you’re sharing it.”

Folk arts also includes hybrids, forms that mix and match, appropriate freely, and serve as metaphors for the confluence of cultures. Playful sculptures by Ontario resident Ernesto Guijarro, for example, challenge folklife categories. “Fishing Boy” is occupational folk art, welded from spare parts in the shop in Ontario where he works. It represents Guijarro’s Mexican heritage and the ingenuity he learned from welding in his uncle’s shop in Fresnillo, Zacatecas. In his homeland, Ernesto says, people learn to do “impossible things” out of necessity. His work is folk art but also an idiosyncratic expression of his vision, revealing change and continuity, work and play, seriousness and whimsy. All meld into the broader pattern of folk expression in eastern Oregon.

© Joanne B. Mulcahy, 2005. Revised and updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

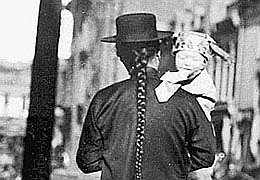

Frankie Dougal and Ropemaking

This photograph, taken by Lynn Hadley on July 27, 1998, shows Frankie Dougal (left) and her daughter, Charlene Standford (right), twisting strands of horse hair into rope. Hadley …

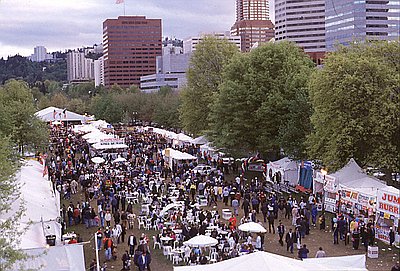

Cinco de Mayo Festival

Portland's Cinco de Mayo Fiesta is held annually at Portland's Tom McCall Waterfront Park and is organized by the Portland Guadalajara Sister City Association (PGSCA). The three-day Fiesta …

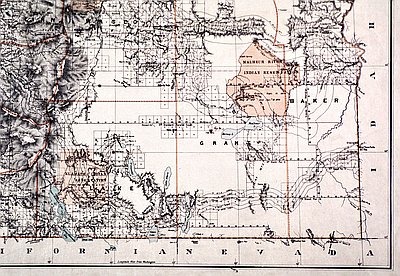

Malheur Indian Reservation

This detail from an 1879 General Land Office map shows the Malheur Indian Reservation in southeastern Oregon. An 1872 executive order by President Ulysses S. Grant established the …