Losing the Land

The Cayuse, especially, resented the growing number of settlers coming across the Oregon Trail in the 1840s and the Whitman missionaries, whom they blamed for an outbreak of measles. When some Cayuse killed a dozen people associated with the mission in 1847, it touched off the first Indian war in the Pacific Northwest. Willamette Valley volunteers often attacked Indians indiscriminately. After two years of conflict five of the Cayuse who had participated in the initial killings turned themselves in and were hung. The Cayuse ceded much of their land, then joined the Umatilla and others in the Yakima War that began in 1855, which also ended poorly for them.

The Nez Perce managed to avoid warfare for several decades. Some continued to practice agriculture and Christianity even after their mission closed in 1847, and most lived on the reservation that opened in 1855. They had reserved 7.5 million acres of land in the treaty of 1855, including most of what would later become Wallowa County, but this land base was reduced to less than a million acres in the early 1860s when gold was discovered in the area. Much of the land removed from the reservation was occupied by Chief Joseph’s band, a traditionalist group that lived in the Wallowa Valley. Although they tried to avoid contact with whites, this proved more and more difficult as settlers moved into the valley in the 1870s and the federal government insisted that they move to the much reduced reservation. These Nez Perce decided to flee to Canada in 1877 after several of their young warriors killed some white settlers. This remarkable fighting retreat, the Nez Perce War, led by just 150 men over 1,300 miles, stalled in Montana just short of the Canadian border, where Chief Joseph (Hin-mah-too-yal-lat-kekht) proclaimed that he would “fight no more forever.”

Groups who signed treaties with the federal government sooner rather than later generally received much better treatment. Hallalhotsoot, whose negotiating skills prompted whites to call him the Lawyer, led a contingent of about 3,000 Nez Perce who in 1855 had signed a treaty providing a reservation that included part of their original territory, and he provided the U.S. with warriors to help fight other Indian nations—though many years would pass until promised goods and services finally flowed to the reservation. The seminal 1855 treaty council also created the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla nations relinquished more than 90 percent of their more than six million acres, though they retained the right to hunt, fish, and gather on their traditional lands.

Chief Joseph and the ragged band of 350 Nez Perce who surrendered late in 1877 were promised a reservation close to home. The government instead sent him to Kansas, the Indian Territory in Oklahoma, and then to the Colville Indian Reservation in eastern Washington.

Most of the conflicts of the Columbia Plateau took place outside the boundaries of what would become Oregon. But several skirmishes in the Cayuse War of the late 1840s occurred along the south side of the Columbia River, and Cayuse and Umatilla warriors were among the combatants in a fight in the Blue Mountains in 1856, part of a series of battles in the drawn-out Yakima War.

The major forts were also located outside northeastern Oregon, at The Dalles and Walla Walla. But several short-lived camps or forts were established in the area, such as Camp Watson, near Mitchell, erected in 1864 by Oregon volunteers to protect a road from Snake Indians.

Many territorial and federal soldiers moved through northeastern Oregon. The white militia of the Cayuse War came largely from the Willamette Valley. Subsequent soldiers were usually part of the U.S. Army, though local residents also participated. Through force of arms and treaties, the federal government removed Native peoples from nearly all of the land that white settlers coveted—then surveyed that land and granted it to settlers.

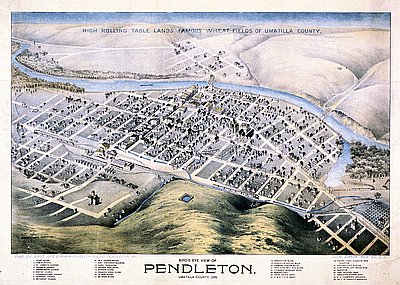

After 1863, the Nez Perce Reservation lay just east of Oregon, in Idaho, and the Warm Springs Reservation was located in central Oregon, south of The Dalles. So the Umatilla Indian Reservation, established by the 1855 treaty and located east of Pendleton, was the only one in northeast Oregon. Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples began moving there in 1860.

The reservation quickly shrank as white farmers and townspeople demanded that it be “opened up.” The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 both divided tribal land into individual allotments that Indians sometimes sold and made the non-allotted land available to non-Indians. By 1890 only a little over 150,000 acres remained, and much of that was lost in the coming years or was rented to non-Indian farmers. The reservation had about 1,000 residents in the late nineteenth century, many of whom kept gardens and cattle while also engaging in fishing, hunting, and gathering. Catholic and Protestant schools educated their children and white teachers tried to get them to dress, speak, and act as Caucasians.

The Indian wars and the seizing of Indian land were dramatic episodes in a tradition of outsiders bringing rapid change to northeastern Oregon, a tradition that would continue to shape the area’s history.

© David Peterson Del Mar, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

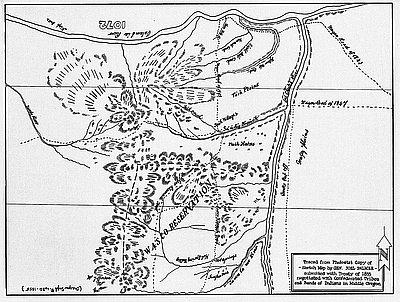

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

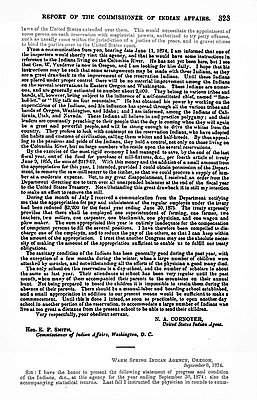

River Indians and Reservation Indians

This excerpt from an 1874 report by N.A. Cornoyer, agent for the Umatilla Indian Reservation, describes the development of a new geography of Native identity in the latter …

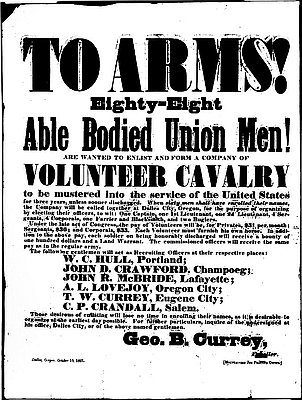

Broadside, To Arms!

This broadside was a recruiting poster printed for Captain George B. Curry by the Mountaineer Job Printing Office in October 1861. Captain Curry raised Company E of the …