Country and Cities

The long-standing trend toward larger and more capital-intensive farms in northeastern Oregon’s wheat belt has accelerated since World War II. New fertilizers and pesticides and disease-resistant strains increased yields. Mechanization continued. Around 1940 the average wheat farm had about $5,000 worth of machinery. Three decades later, in 1969, that figure had risen to over $50,000.

Some of the region’s farmers have done very well, though increased competition from growers across the globe has cut profits and prompted diversification. Many others have had to sell their land, often to large farming corporations owned by interests located far outside the area’s borders, like J.F. Simplot, whose annual sales exceed $3 billion. Threemile Canyon Farms appeared near Boardman early in the twenty-first century. It bought 93,000 acres from the state and provides 250 year-round jobs.

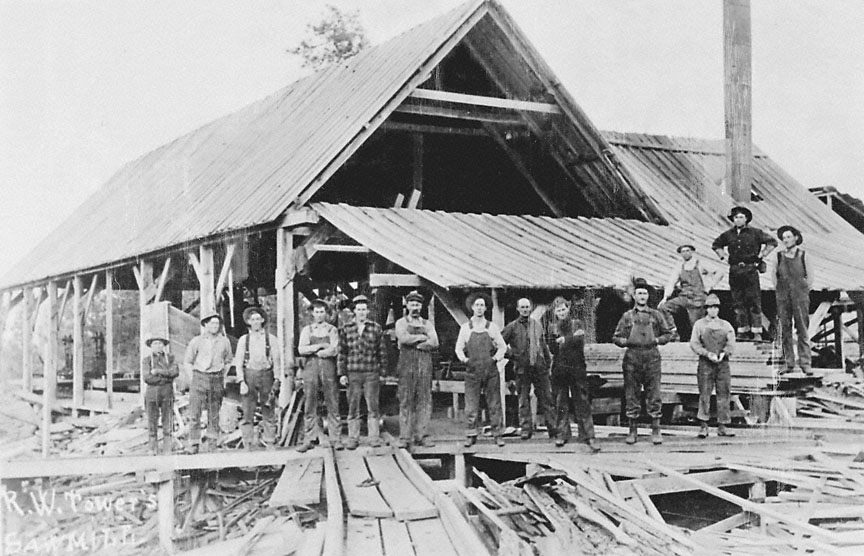

Logging continued to dominate the area’s manufacturing in the 1950s and 1960s. Eastern Oregon’s share of the state’s timber production rose during these years, and logging and mills were a key part of the economy in Union, Baker, Wallowa, and especially Grant counties.

But all four of these counties lost at least two mills in the century’s last two decades. By 1998 Grant County had just 339 manufacturing jobs, nearly all of them in lumber. The area’s industrial leaders were Umatilla, Union, Malheur, and Morrow counties, and in all but Union County jobs in food manufacturing dwarfed timber. Global competition, technological improvements, and government regulation combined to dramatically reduce the number of timber jobs.

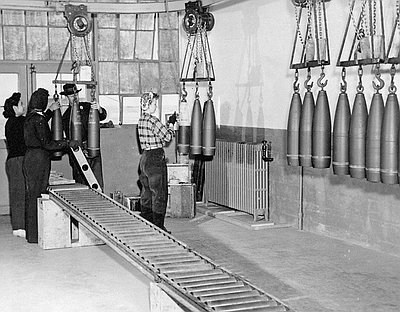

Northeastern Oregonians tended to distrust government, but they benefited from increased government spending over the past several decades. Each of the area’s counties exceeds Oregon’s average in government employment as a percentage of total employment. Fully one quarter of Grant County’s employees work for the federal, state, or local governments, twice the state average. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management own large portions of Grant, Wallowa, and Baker counties and employ many of their residents. The Umatilla Army Depot and McNary Dam, both near Hermiston, are also major federal employers.

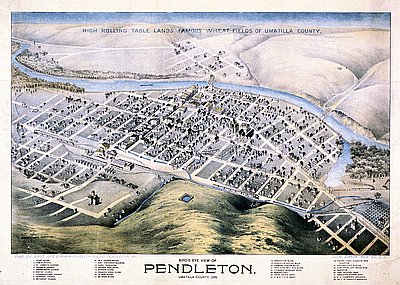

The state government also provides many jobs. Eastern Oregon University in La Grande and Blue Mountain and Treasure Valley community colleges, in Pendleton and Ontario, respectively, are state-run post-secondary institutions. Three of the state’s largest prisons are in Ontario, Umatilla, and Pendleton.

But the expansion in government jobs has only partially compensated for the decline of timber jobs and independent farms, trends that threaten the region’s tradition of resource extraction and independence.

Ontario’s population has expanded at an impressive rate, from just over 6,500 in 1970 to nearly 11,000 in 2000. Agriculture—including potatoes, onions, and sugar beets—remains the staple, and food processing is the city’s largest employer. Ontario relies heavily on large businesses that employ many wage laborers.

Hermiston has grown more rapidly than any of the area’s cities, expanding from less than 5,000 in 1970 to over 13,000 in 2000. Its proximity to major transportation lines—the Columbia River, railroads, and the interstate highway—have helped. Its economy is the area’s most diversified, with government employment, a mobile home manufacturer, the Union Pacific Hinkle Railyards, and Portland General Electric joining the traditional staples of farming and food processing. Wal-Mart built a large distribution warehouse there in the late 1990s.

As before, mechanization has made for larger and fewer farms. By 1969 Umatilla County had only 300 wheat farms, down from 500 less than twenty years before. The timber industry’s decline also drove many loggers and mill workers and their families from northeastern Oregon. Baker City’s population expanded only slightly from 1950 to 2000. La Grande and Pendleton did better, but grew more slowly than the state as a whole. Rural areas did far worse. Gilliam County lost a quarter of its population from 1950 to 1975. Wheeler, Gilliam, Sherman, Wallowa, Grant, Morrow, and Baker counties lost population in the twentieth century's last half; in 2010 they constituted seven of the state’s smallest nine counties.

With the exception of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the area became racially homogenous after the decline of the Chinese population late in the nineteenth century. According to the 2010 census, the ten counties count an average African American community of 0.54 percent and an average Asian American population of 0.72 percent. This changed dramatically a century later, as thousands of immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Latin America made their way to the fields of Malheur, Umatilla, and Morrow counties. In the 1960s, for example, the census count of Latinos in Umatilla County grew from 746 to 2,682 and measured 18,9189 in 2012. Latinos are a very large portion of the population around Ontario, Vale, and Nyssa, constituting 32.5 percent of Malheur County as of 2012, and make up a third of Morrow County, the highest percentage in Oregon. The Ontario area is also home to a significant Japanese American community, with many settling in the area during and following World War II.

The newcomers have not always been welcomed. On the one hand, these immigrants have chosen to come to northeastern Oregon, and many have done very well here. Their growing numbers have enabled newcomers to join an established yet familiar Spanish-speaking community. But taverns in and around Nyssa posted “No Mexicans Allowed” signs early in the 1960s, and a study done a decade later found that Latino parents believed that teachers both disciplined their children more harshly and gave them less instruction than white children. In the 1960s the Office of Economic Opportunity funded a wide range of social and educational opportunities in Ontario area. Educational activities have allowed a growing number second-generation Latinos, especially, to move into professional jobs and to start successful businesses serving residents inside and outside its growing Latino community.

The area’s Latino community has become more diverse, with a growing number of native-born joining the educated, middle class, even as newcomers continue to be drawn by wage work in farms and factories.

© David Peterson del Mar, 200. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Mexican Laborers Weed Sugar Beet Field

This photograph shows Mexican citizens weeding and thinning in an unidentified sugar beet field in Oregon, probably in Malheur County, during World War II. In 1942, the United …

Workers at the Umatilla Ordnance Depot, 1943

This photograph shows workers at the U.S. Army’s Umatilla Ordnance Depot stenciling and inspecting 155-millimeter artillery shells. It was taken by an Oregon Journal photographer in April 1943. …

Eastern Oregon Normal School

This photograph of the Eastern Oregon Normal School was taken by Wesley Andrews around 1929. Andrews was a professional photographer who had studios in Baker City and Portland. …