Post-War Malaise and Home Front Boom

When war production came to a halt and the Kaiser shipyards rapidly closed, over 125,000 people lost their jobs. Temporary declines in aluminum and timber production just after the war also diminished employment prospects. But the city’s overall population did not decline appreciably because people preferred to stay. The state’s economy inexorably shifted from agricultural and timber processing to manufacturing. The national post-war housing boom expanded timber cutting in Lane and Douglas counties, and Portland remained the center for furniture, pulp, and paper production. Specialized clothing production at Jantzen, Pendleton, Norm Thompson, and White Stag also expanded, and the latter company’s red-nosed deer became an icon on a waterfront billboard. Two new oil refineries and new factories for national companies like Willard Batteries, Quaker Oats, and Nabisco were built.

Richard Neuberger, soon to be elected to the state legislature and then to the United States Senate, explored the post-war discontent in the city in an article in The Saturday Evening Post. He argued that the abundance of cheap hydro-electric power should be attracting a variety of new industries, yet the business and political leadership were possessed by what he called a “municipal schizophrenia.” Mayor Earl Riley and the real estate interests preferred pre-war patterns of slow growth because they feared that rapid expansion would attract a multi-racial working class for whom they would have to find housing. Younger men, Neuberger said, wished to utilize the new power to attract more heavy industry.

In the wake of accusations of corrupt practices in the police department, Riley faced intense criticism from businessmen like Arthur Ward, an insurance executive, who wrote to Richard Neuberger, “I believe it is time we clean up our entire city government and clean the slate.” Riley failed to succeed in his bid for reelection in 1948 and was replaced by city commissioner Dorothy McCullough Lee, a respected lawyer, who became the city’s first female mayor. While in the state legislature in the 1930s, she had supported increased state funding for schools and for retirement pensions. In August 1943, she was appointed to fill a vacancy on the Portland city council, where she also became the commissioner of public utilities and gained a reputation for being honest and efficient.

In office, Lee advocated “municipal housekeeping” to support new business activity, like getting the public transportation company to change the remaining streetcar line to busses. She also initiated a one-way grid on downtown streets to allow a more rapid movement of traffic. But she got most publicity for addressing the issues that forced Riley out of office. She enforced statutes that outlawed slot machines and gambling in private clubs, and insisted that the police eliminate roving prostitutes. But she seemed uninterested in the larger issues of growth: promoting new industry and finding affordable housing for lower income residents.

The Lee administration’s key problem, like that of her predecessors, was a lack of revenues, exacerbated when the electorate in May 1950 rejected a business tax, a city service tax, and funding for low-rent housing. A supporter of civil rights, Lee got the city council to pass an ordinance outlawing racial discrimination in public places, but a citizen’s petition stopping the ordinance was passed at the November 1950 election.

Though Lee saw herself as a mayor enforcing laws against immoral behavior and was endorsed by the Oregonian and the Oregon Journal, the electorate apparently tired of her enthusiasms, and she lost her bid for reelection in 1952 to a male opponent who billed himself as a “businessman.” After leaving office, Mayor Lee was appointed by Dwight Eisenhower to the Federal Parole Board and later to the Subversive Activities Control Board, to which she was reappointed by President Kennedy. She and her husband lived in Washington, D.C., until returning to Portland in 1962.

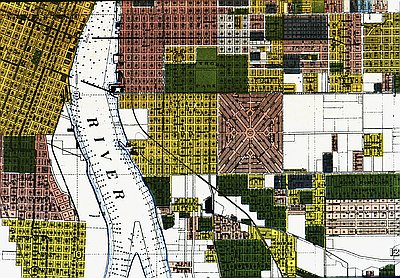

As plants tooled up in 1940 to produce war materials for Britain, inexpensive hydropower received heavy federal subsidies. Between 1941 and 1945, Congress poured over $2 billion into the Bonneville Power Administration on a crash program that increased its generating capacity sixfold. In 1941, Henry Kaiser, who had helped construct Boulder, Grand Coulee, and Bonneville dams, had been awarded contracts to build liberty ships and aircraft carrier escorts. He selected Portland as one of his West Coast sites and soon built a large shipyard at Vancouver and two more along the Willamette River in Portland. Kaiser then recruited 150,000 new workers, some who arrived on special trains from as far away as New York. During the war, Portland gained 160,000 people, boosting its population to 359,000, with another 100,000 newcomers working in Troutdale, Oregon City, Vanport, and Vancouver.

War contracts further connected Portland with the federal bureaucracy and the federal budget. While slum clearance and coordinated highway, bridge, and public housing construction were already evident in New York and Chicago, the rapid construction of industrial plants and public housing arrived in most western cities during World War II. War production forced Portland, like Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Las Vegas, to enter a new economic relationship with the federal government that would dominate urban politics at least through the Reagan Administration. While New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia political leaders welcomed that relationship, mayors and councilmen in Portland tried to resist it.

Portland, however, did not remain as stagnant. On August 1, 1960, the Lloyd Center, which was advertised as the largest shopping center in the world, opened between Northeast Ninth and Northeast Sixteenth Avenues. With over a hundred stores, including a Meier & Frank and the largest Woolworth’s and Newberry’s in the region, the center challenged the downtown business district. The idea for the center began in 1923, when Ralph B. Lloyd, an oil company executive from southern California, became the only major outside investor to enter the Portland real estate market. Lloyd wanted to build a self-sufficient region, with homes, stores, and a residential hotel on fifty acres near Grand Avenue and Northeast Glisan Street. The project was delayed by the Depression, World War II, and the refusal of voters to pass bond issues to improve nearby streets.

Lloyd died in 1953, but his family corporation, with backing from the Prudential Life Insurance Company, changed plans and went ahead. When the center was finally completed, it had a Sheraton Hotel, office space for government agencies like the Bonneville Power Administration, and a galaxy of stores that Time called a “consumer’s cornucopia.” A few blocks to the south, an interstate freeway was being constructed, with connections across the Marquam Bridge to the west side.

Less than a year later, the architecturally innovative Memorial Coliseum opened just above the east bank of the Willamette and about a half mile west of Lloyd Center. Voters had selected the site, which was one of Portland’s early African American neighborhoods, in preference to a larger area designated for urban renewal on the west side. Despite the cramped area for exhibition halls and parking, the structure was meant to give Portland an image of strength that made it a landmark of twentieth-century public architecture.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

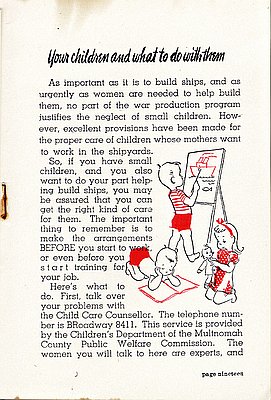

Handbook for New Women Shipyard Workers

In 1943 Portland Public Schools produced a handbook designed to orient new women workes to life in the shipyards. One section dealt with the problems of childcare. During World War …

Kaiser & Oregon Shipyards

In 1940, Henry J. Kaiser signed an agreement with the British government to build 31 cargo ships to aid that country in their war effort. After scouting several …

Nightshift Arrives Portland Shipbuilding

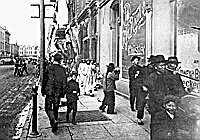

During World War II, up to 125,000 people worked in around-the-clock shifts at shipyards in Portland and Vancouver, Washington. This photograph, taken by Ray Atkeson, shows nightshift workers …