New Transportation Network

Portland became a mature processing and distribution center between the 1880s and 1914 as it joined the new national railroad network. As work proceeded after the Civil War on the first federally subsidized transcontinental trunk line from Omaha to San Francisco, business leaders in Portland, like those in other western towns, realized they would have to be connected to the system if they were to prosper. The routes to the Pacific Coast, however, were being built through sparsely settled regions that generated little freight or passenger traffic until each would connect with a Pacific hub. Their construction companies had to borrow huge sums and owed millions to bondholders. Because the financial demands of railroad construction were so high, the stories of construction are filled with bribery to obtain government subsidies, failure to complete routes, and bankruptcies. The story of Portland’s connection is no different.

At first, merchants in Portland and Salem assumed that their connection to the east would require construction of a railroad to San Francisco. By April 1867, each group had incorporated a line, one to proceed down the east bank and the other down the west bank of the Willamette River. Neither group could raise the capital to proceed very far, so by 1870 Ben Holladay, a flamboyant stagecoach and steamboat operator from San Francisco, had gained control of the eastside company. He bribed legislators to transfer the railroad franchise, and then sold bonds to finance construction. Holladay built through to Roseburg by 1872, when he ran out of funding. When his German investors learned he could no longer pay interest on the bonds, they sent a German American journalist, Henry Villard, to take control.

By the late 1870s, however, additional trunk lines to the West Coast were being built, primarily by Chinese laborers, and Portland and Los Angeles each hoped to become a terminal. Villard used the assets of this investors to buy the Northern Pacific Railroad, which had built west from St. Paul to Spokane, and then down the south bank of the Columbia River to Portland. Triumphantly, Villard brought his first train, with 300 guests, into Portland on September 11, 1883. Within four months, however, the Northern Pacific faced bankruptcy, and New York banker J.P. Morgan forced Villard to sell the railroad. Villard and his investors, however, still controlled the rail line through the Willamette Valley. They completed track to Ashland by 1886, when they ran out of money. The Southern Pacific Railroad, after much secret negotiating, acquired the line and completed the link to California. The first through train from San Francisco arrived in East Portland on December 19, 1887.

During the construction of the railroads, the scramble for franchises and government subsidies for terminal rights in Portland and for private funding changed the political culture of the city. Not only the bribes to legislators but also the fees earned by railroad lawyers and lobbyists and the secretive banking and political connections to New York and Washington created a more sophisticated if cynical atmosphere among the city’s elite. The Oregon Supreme Court on several occasions had to decide which franchise grants should supersede others and which railroads should have access to which terminals. The Court often contradicted itself, with onlookers wondering about the integrity of the jurists. By the end of the 1880s, the most influential lawyers and politicians—including John H. Mitchell, Cyrus Dolph, and Joseph Simon—were as notorious for their allegiance to specific railroad interests as for their political affiliations.

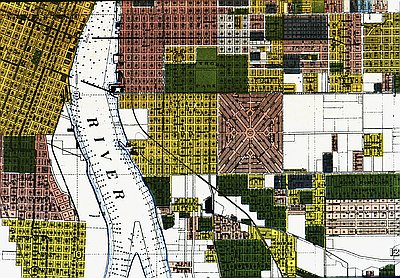

In addition, new demands were made on the city’s landscape. Tracks traversed city streets to reach terminals, and high-speed trains created new dangers to pedestrians and horsedrawn vehicles. People demanded that railroads erect warning signals at traffic crossings or even lower the roadbed or build bridge crossings over major streets. The railroads also created other demands on city budgets. The Willamette River through the early 1880s had been crossed only by ferry. But as the population grew rapidly on the east side because of the railroad yards, car maintenance shops, and small machine shops, downtown merchants, and eastside residents wanted access to one another whenever they wished rather than according to a ferry’s schedule. The construction of bridges to serve not only pedestrians and carriages, but also horsedrawn and then electrically powered public conveyances would require voters’ approval of new bonds. Taxes, of course, would have to be raised to pay the new public debts. Between 1885 and 1895, the city council allowed private companies to build dozens of streetcar lines on public rights-of-way. By 1900, 128 miles of trolley track ran through the city, spurring the development of the east side. With an increasing number of immigrants settling in Portland, the east side became home to a growing number of ethnic enclaves.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHS staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

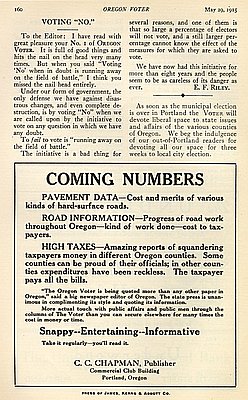

Letter to the Editor, Voting No

This letter to the editor written by E. F. Riley was published in the May 29, 1915 issue of the Oregon Voter, a conservative weekly magazine issued between …

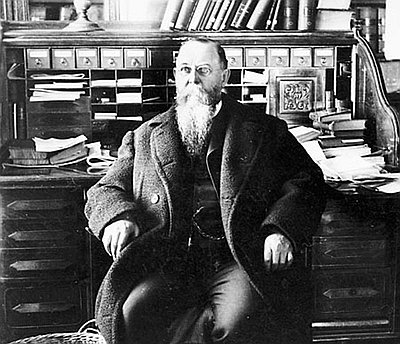

John H. Mitchell (1835-1905)

This circa 1898 photograph shows John H. Mitchell, a U.S. Senator elected by the Oregon state legislature in 1874, 1885, 1891, and 1901. He wielded substantial power in …

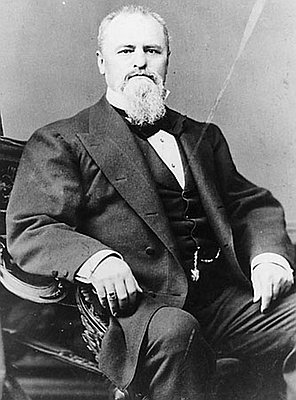

Ben Holladay (1819-1887)

Ben Holladay was a businessman involved in the stagecoach and railroad industry in the West. He was responsible for many of the stageline roads and railtracks in western …