Suffrage and the Oregon System

Male politicians slowly expanded their concept of progress to include the enfranchisement of women, but women had already developed a broader agenda that they wanted to bring into the political arena. One of the leaders in the campaign for women’s suffrage in Oregon was Abigail Scott Duniway. In 1871, Duniway sold her millinery shop in Albany to manage the New Northwest, a newspaper in Portland. She intended to promote broadly egalitarian views, especially legal autonomy for married women. By the time she sold the paper in January 1887, she had induced the legislature to erode the patriarchal context in which married women remained subordinate. During the 1870s, it became legal for married women to own businesses and property, to keep their earnings despite debts incurred by their husbands, and to vote in school board elections.

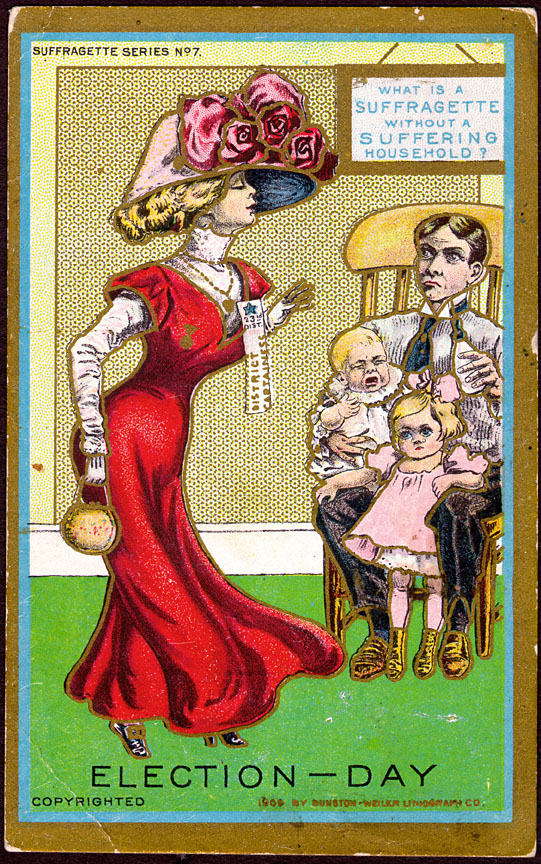

By 1883, two successive legislative sessions had passed laws enfranchising women. When the proposed amendment went before the male electorate in 1884, it received a majority of the votes in the rural counties, but lost statewide because of overwhelming opposition in Portland’s working-class districts. In the late 1890s, women’s suffrage again passed in two successive legislative sessions, but again lost in a statewide election. After the system of initiative and referendum was adopted in 1902, proposed amendments no longer required approval by the legislature, but Duniway did not believe that Oregon’s voters were ready to reexamine the issue. After the states of Washington and California approved women’s suffrage, she agreed in 1912 to sponsor a new referendum, which finally passed.

By then, female doctors, nurses, and settlement volunteers, working through women’s benevolent groups, had made the protection of children and women legitimate concerns of local government. Dr. Marie Equi established a practice in Portland and treated primarily women and children, often at no charge. She advocated for eight-hour workdays, prison reform, and state-supported higher education, in addition to women’s suffrage. In 1907, suffrage activist Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy became Portland’s city health officer, the first woman in a major U.S. city to hold such a position. She made public health issues priorities in the city, including improved garbage collection, pure food and milk, and inspection of school children for communicable diseases. Largely through campaigns by women’s clubs, by 1907 the city had created a juvenile court and a house of detention to separate the oversight of juvenile offenders from the punishment of adults. In 1902, the Council of Jewish Women opened a settlement house in the South Portland immigrant neighborhood. They soon suggested that social services carried out there, like preventive medicine and dentistry, after-school recreation, and vocational education, become regular functions of the public schools. Women were elected to the school board in part to assure that school administrators would implement these reforms.

In the decade before World War I, Portland developed a series of innovations in direct democracy called the Oregon System. The reforms were proposed in the 1890s to counter what spokesmen for small businessmen and labor unions perceived to be undue influence on government by corporate interests. Incentives for changes in city government were precipitated when Portland General Electric, between 1905 and 1907, organized a series of mergers under the name of the Portland Railway Light and Power Company. The new corporation included interurban rail lines and electric companies in Portland, Salem, and Vancouver. The mergers required the infusion of $8 million of capital from a Philadelphia banking family, which now controlled Oregon’s largest utilities. People like William S. U’Ren, Will Daly, Harry Lane, and Abigail Scott Duniway presented a new vision to encourage voters to participate in government so they might countervail against corporate power.

U’Ren, who had some legal training, had arrived in Oregon in the early 1890s and settled near Oregon City. As the Populist Movement won victories in the Plains states, he hoped to empower Oregon’s voters to initiate legislation by petition and to subject new laws to popular referendum. Serving in the legislature in the late 1890s, he followed the constitutional requirement and forced two successive legislatures to pass the initiative and referendum amendments. After extensive promotion through leaflets, pamphlets, and newspaper advertising, a state plebiscite in 1902 approved the amendments by over ten to one. In an article in the Arena in 1903, U’Ren argued that the reforms were hardly radical, but represented a consensus among businessmen, bankers, former governors, congressmen, and key labor leaders on how to empower the public.

By 1905, U’Ren’s People’s Power League had placed a series of initiatives on the ballot, including a direct primary measure that allowed voters to express a preference for a United States senator, even though the federal constitution still required election of senators by state legislatures. Most of the initiatives passed. The momentum of the People’s Power League for direct democracy reached its limit in 1912, when several initiatives, including the abolition of the state senate to create a unicameral legislature, were defeated.

In Portland, the goals of the Oregon System were best expressed in the mayoral tenure of Harry Lane, who had had a twenty-year career as a Democrat with Populist leanings. The grandson of Joseph Lane, Oregon’s territorial governor and first United States senator, Harry Lane had grown up in Salem and graduated from Willamette University Medical Department. In the 1890s, he settled in Portland, where his bent for political activism led to his successive elections as president of the city, county, and state medical societies. In 1905, he announced his candidacy for mayor of Portland as a Democrat. In office, he followed the usual Progressive civic agenda on behalf of citizens as consumers. He fought street railways and the Portland Railway Light and Power Company over franchise provisions, and with pressure from ministers and women’s clubs, he reluctantly moved to close brothels and saloons, which he saw as places of recreation for workingmen. His positions proved popular, and he was reelected in 1907.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

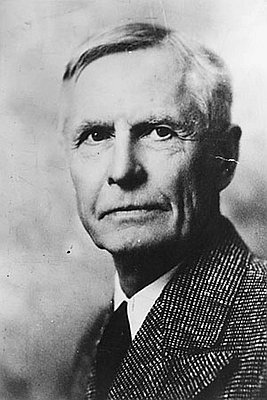

William S. U'Ren (1859-1949)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Oregon was known for its experiments with democratic reform. The state developed a system of government that came to be known …

Typewriter Belonging to Abigail Scott Duniway

This portable Blickensderfer typewriter belonged to Abigail Scott Duniway, who doggedly worked for women’s suffrage beginning in the 1870s. In 1912, voters finally passed an amendment to Oregon’s constitution …

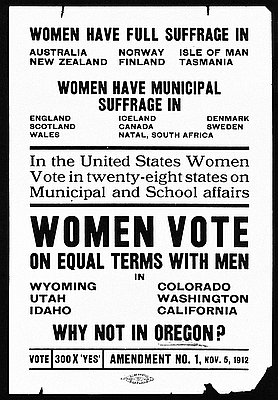

Women's Suffrage Handbill

The Oregon chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League produced this handbill as part of a successful 1912 state campaign to give women the right to vote. Newspaper …