New Pace for Growth

From 1900 to 1914, Portland was the third fastest growing middle-sized city in the United States, behind Los Angeles and Seattle. Los Angeles owed its growth to the most varied developments, a chamber of commerce promoting the city as a haven for retirement, the annexation of the San Fernando Valley to increase the tax base, the development of a new motion picture industry; and the discovery of oil. By 1920, its population exceeded half a million, making it the largest city on the coast. From 1900 to 1910, Seattle grew quickly as a supply center for the gold rush to Alaska and as the closest port for trade with Japan and Siberia. It surpassed Portland in size and has retained that status as the region’s largest city ever since. Magazine articles describing Portland’s growth emphasized its traditional geographic advantage: the unique access by rail through the Columbia River Gorge to the Inland Empire, whose agricultural production proliferated because of irrigation.

Pushing to expand with their coastal rivals, Portland’s business elite promoted the Lewis and Clark Exposition of 1905 to mobilize civic interest and attract national publicity by placing a patriotic veneer on the expansion of trade. The fair was modeled after larger expositions in Chicago and St. Louis, which had celebrated technological innovation and civic cohesiveness. The importance of technological improvements as the theme of the exposition was clearly dramatized in 1903, when Henry W. Goode, head of Portland General Electric, replaced Henry Corbett as president of the fair board. Goode supervised overall construction, while his company collected the fees for turning night into day at the fairground. As in Chicago in 1893, the buildings for the Lewis and Clark Exposition were placed around a lagoon. Portland’s exposition, however, was situated on rented land at Guild’s Lake, beyond Union Station’s railroad yards, not on a publicly owned lakefront. Developers, not the public, would determine the fate of the site.

The promotional intent of the fair was visible in the funding, as the private fair board, after investing their own capital, successfully sought subsidies not only from the city but also from the Oregon legislature, the legislatures of other states, and the federal government. The fair’s exhibits, like those at Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909, mixed displays of products in buildings sponsored by local industries and by states like Washington and California. Simulated villages of Filipinos and Alaska natives represented quaint cultures that would be swept away by new American technologies. Members of the Igorrote tribe, shipped from the Philippines to Portland for the fair, were treated more as spectacle. Described and housed as inferiors, they were an example of colonial attitudes in the United States in the early twentieth century.

While the great majority of the people attending the fair over the summer of 1905 were local, the publicity was national. A spate of richly illustrated magazine articles by Walter Hines Page, Edgar Piper of the Oregonian, Donald MacDonald, and Robertus Love contrasted the beauty of the region and the unique qualities of some of the fair’s buildings with the opportunities for trade in local raw materials and for office space in the city’s modern buildings.

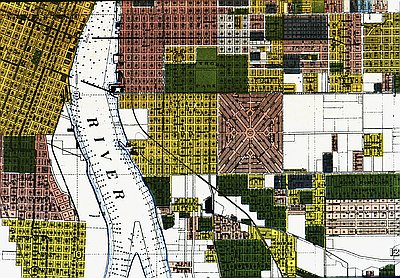

The Exposition’s buildings, however dramatic in appearance, were intended to be temporary. Beginning in 1910, F.N. Clark, a real estate developer for the Ladd estate, began to lay out portions of Guild’s Lake and the highlands of Westover Terrace for sale. The fair itself was perpetuated in the Rose Festival, which carried forward the theme of the city beautiful. The parade that highlighted the Rose Festival became the most publicized of many parades featuring open trolley cars moving through the business core along Third Avenue. The street was decorated with elaborate cross-arches illuminated by electric lights reminiscent of the Exposition.

The city’s image was modernized most conspicuously by tall commercial structures with steel frames and concrete facades that dwarfed the three- and four-story masonry buildings around them. In 1907, Wells Fargo erected a twelve-story tower at Sixth and Oak, which housed the offices of the Southern Pacific and the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. In 1910, Meier & Frank built its twelve-story tower at Fifth Avenue and Morrison Street, which beckoned to middle-class consumers. In internal organization, marketing techniques, and amenities for shoppers, the department store was modeled after the paragon of consumer emporiums, John Wanamaker in Philadelphia. Herbert Croly, in a brief survey of Portland’s varied architectural styles for the Architectural Record in 1913, wrote that the Spaulding Building “is as good of its kind as any which has been designed in the past couple of years in any other American city.”

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

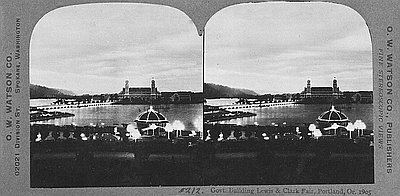

Night View of the Lewis and Clark Fair

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition and Oriental Fair in Portland was illuminated at night by 100,000 lamps that outlined the graceful fair buildings, streets, and walkways. “No …

Central Vista, Lewis & Clark Centennial Expo

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition was the West Coast’s first worlds fair. This central vista shows the Foreign Exhibits Building on the left, and the Agricultural Palace on …

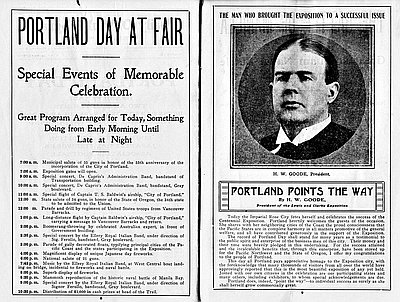

Program for Portland Day at the Fair

This Sept. 30, 1905, program is from “Portland Day” at the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair. Shown here are the middle pages …