Resettlement

Because the Pacific Northwest was a focus of international commerce in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, people of many different cultures came to or passed through the region. The earliest Europeans to stay for long on the northern Oregon coast were the Scottish, English, French, and American people attached to British and American fur-trading enterprises. The fur companies recruited Hawai‘ians to work as seamen on company ships and as laborers ashore, and an estimated 1,000 indigenous Hawai‘ians traveled to the Pacific Northwest between 1787 and 1898, when the islands were incorporated into the United States. The HBC post at Fort Vancouver employed Hawai‘ians to work in the company’s gardens and water-powered sawmill, the first in the Oregon Country. Umatilla, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Nez Perce regularly traded with the HBC, and some of the company men married Native wives. Since the 1860s, however, the population of the Oregon Coast and the Pacific Northwest as a whole has been predominantly Euro-American.

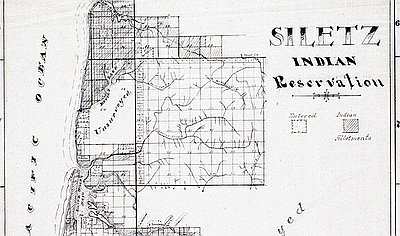

The HBC had a tremendous impact on the Native peoples on the coast. Archaeologist Scott Byram argues that the Yaquina, an ancestral tribe of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, was one of the first Native groups in western Oregon to suffer the direct effects of colonialism when, in the spring of 1832, they had a series of violent conflicts with HBC fur trappers. Company accounts justified the violence as retaliation for the murder of two trappers, while Native oral tradition describes the events as the beginning of the decline of the Yaquina. In 1855, Yaquina Bay, the site of the violence, was made part of the Coast Reservation. Ten years later, it was opened to white settlement and the people there were ejected from their ancestral homelands.

In April 1841, the United States Exploring Expedition, led by Lt. Charles Wilkes, arrived off the Columbia River bar near present-day Astoria. The Peacock, part of the expedition’s flotilla,was lost on the bar, although all of its crew and supplies were rescued. “Mere description can give little idea of the terrors of the bar of the Columbia,” Wilkes wrote, concluding that the river was inaccessible. Members of the expedition explored the Oregon Country overland, collecting demographic and ethnographic data from their interactions with Native groups.

The first whites on the Oregon Coast settled south of the Columbia on Tillamook Bay in 1851. “I left the Columbia in a whale boat with provision for six months,” wrote Joe E. Champion in his journal. He and two companions, Samuel Howard and W. Taylor, entered the bay the next morning. “The Indians generally seemed pleased with the prospect of having the Whites to settle among them (Poor Fools),” he wrote; “they showed me a large hollow dead Spruce Tree, into which we conveyed all my property. I christened it my Castle.”

In June of that year, nine men sailed from Portland in the steam schooner Sea Gull,captained by William Tichenor, to establish a trading post in present-day Port Orford. The newcomers received a chilly welcome from the local Tututni and responded in kind. “There were a few Indians in sight who appeared to be friendly,” the leader of the expedition, J.M. Kirkpatrick, later wrote, “but I could see that they did not like to have us there....We lost no time in making our camp on what was to be called Battle Rock.” The men set up their cannon on the narrow protuberance in the small harbor and trained it on the spine of rock that sloped down to the beach.

Kirkpatrick described what happened next:“When...a red shirted fellow in the lead was not more than eight feet from the muzzle of the gun, I applied the fiery end of the rope to the priming….At least twelve or thirteen men were killed outright.” The intruders told the Tututni that the ship would return in two weeks and hunkered down on the rock to wait. When the ship did not appear on the appointed day, the Tututni advanced on the visitors. By the time the would-be settlers fled the harbor with only but their guns and axes, they had left about twenty Tututni dead, including the headman.

Settlement of the marshy lands around the estuary of the Coos River began with a shipwreck. A federal troop ship, the Captain Lincoln, left San Francisco in December 1851 intending to deposit soldiers at Port Orford to prevent any further violence there. The ship sprang a leak, but it could not land at Port Orford because of stormy weather and so limped north. On New Year’s Day 1852, the Captain Lincoln passed the entrance to the Coos estuary and ran aground on North Spit. The captain, crew, and soldiers went ashore and set up a camp, trading with Coos people for food and supplies. Not knowing exactly where they were, they called their settlement Camp Castaway.

The news of the shipwreck spread, and other whites arrived from the Umpqua to help them. One of these, P.B. Marple of Jacksonville, taken with the scenery, resources, and economic prospects of the area, became a walking advertisement for the Coos Bay country after he arrived home. He organized a stock company and collected $250 each from forty young men, vowing to lead them “to this new Promised Land,” as the wife of one of the men wrote in her memoir. “He could easily have secured twice as many members, if he would have taken them.” Marple called his new venture the Coose Bay Company.

In July 1846, Lt. Neil M. Howison arrived at Astoria with orders from President James K. Polk to “obtain correct information of that country and to cheer our citizens in the region by the presence of the American flag.” The president needed support for his hardline position on the United States’ long-running boundary dispute with Great Britain, summarized in Polk’s slogan, “Fifty-four Forty or Fight” (referring to the latitude line of 54 degrees, 40 minutes). The dispute was settled peacefully in 1846, with the Canada-U.S. boundary established at the 49th parallel.

Howison visited “all settled spots on the Columbia below the Cascades [near present-day Cascade Locks], the Wilhammette valley for sixty miles above Oregon City, and the Twality [Tualatin] and Clatsop plains.” By his estimate, the population of the region, exclusive of Native people, was some nine thousand people, nearly all of them settled along the Willamette River, with twenty or thirty families at the mouth of the Columbia. That settlement, Howison wrote, was “in a state of transition, exhibiting the wretched remains of a bygone settlement, and the uncouth germ of a new one.”

Howison left Fort Vancouver in the schooner Shark in August. After the ship was wrecked on the Columbia bar in September, the crew chopped the masts down and jettisoned the cannons in an effort to get the ship off the south spit. All on board were rescued, but the ship eventually broke up. The part of Shark’s hull with the cannons on it came aground south of Tillamook Head, which is how Cannon Beach got its name.

By the late 1840s, the territory’s white population was slowly but steadily growing. The 1846 census for Clatsop County lists 95 people; by 1850, the population had grown to 462. The site of Fort Clatsop on the Lewis and Clark River was homesteaded in 1849 by S.M. Henell of Astoria, under a land-claim law passed by the Oregon Provisional Government. The following year, Thomas Scott jumped Henell’s claim under the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850. Scott traded the property to Carlos Shane, who built a house nearby and burned the remaining timbers of Fort Clatsop to clear the land. Before long, all traces of Lewis and Clark’s sojourn had been erased from the landscape.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Oregon City and Willamette Falls

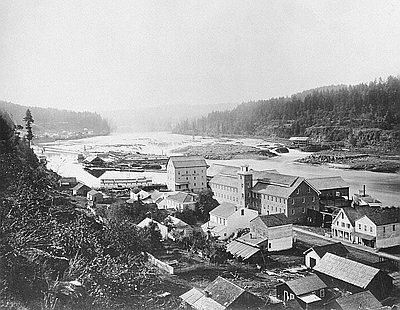

This 1867 photograph, taken by Carleton Eugene Watkins, shows Oregon City and the Willamette Falls soon after the first portage railroad was built there. Oregon City had been incorporated …

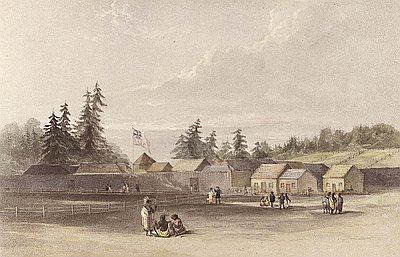

Drawing of Fort Vancouver

This hand-colored lithograph of Fort Vancouver was based on a sketch drawn by Henry James Warre in 1845 or 1846. The British government sent Warre, an army lieutenant, …