Conservation Moves to the Forefront

Since the turn of the twentieth century, two prominent features of the Oregon Coast have been the stunning beauty of its landscape and the dependence of its people on industries that that are hard on the land. It was inevitable that this tension would erupt into conflict between those who would preserve the land for its aesthetic qualities and those who would use it for profit and livelihood.

The 1897 designation of federal forest reserves was the result of a conservationist spirit that focused on protecting resources like timber and watersheds for future use, enjoyment, and profit. In those years, the conservation-development battle was between wasteful use, represented most egregiously by cut-out-and-get-out timber companies, and wise use, represented by the ideal of scientific forest management. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that the nonutilitarian tenets of modern environmentalism—that is, concern for the recreational values, aesthetic qualities, spiritual appeal, and ecological functioning of landscapes—was widely embraced. Through the years, the two strains of conservation have coexisted, often uneasily, in the public discourse about natural resources.

Environmentalism found a forceful spokesman in Thomas Lawson McCall, Oregon’s governor from 1967 to 1975. In the early 1960s, McCall, then a television journalist, gained a name for himself with a documentary called Pollution in Paradise. The film portrayed the degraded condition of the Willamette River and the valley’s industrial artery and one-time recreational asset, now fouled with sewage, pulp-mill effluent, factory waste, motor oil, sawdust, street runoff, and old car bodies.

McCall ran for governor on a platform of “livability,” a term popularized by his predecessor as governor, Mark O. Hatfield. A patrician politician with the common touch, McCall was a plainspoken orator with a flair for the dramatic, a man who knew how to work the media. By the end of his first term, he had pushed more than one hundred environmental bills through the legislature.

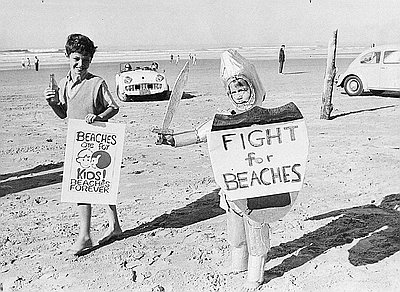

The new governor gained an early and important political victory with the 1967 Beach Bill, which authorized the state to zone Oregon’s beaches to protect them from private development. McCall staged a photo-op in Cannon Beach—some called it a publicity stunt—that all but guaranteed that his bill would pass. According to Willamette Week reporter Patti Wentz: “The single moment that has come to define McCall occurred in 1967. A motel owner had put up a fence on the beach, infuriating McCall, who believed the beaches were public property....he helicoptered onto Cannon Beach, making sure the media would be there to greet him. With TV crews chronicling the dramatic moment, he drew a literal line in the sand between the motel and the incoming tide. The scene aired on the evening news, and the Legislature was shamed into passing the bill.”

In what may be his most famous remark, McCall invited visitors to Oregon, to “come again and again. But, for heaven’s sake, don’t move here to live.” That message was echoed in the road signs at the Oregon-California state line, which read “Welcome to Oregon—we hope you will enjoy your visit.” McCall spoke for many Oregonians in questioning economic growth that came with an environmental price tag. The political sentiment existed before McCall’s tenure. Victor Atiyeh, Oregon governor from 1979 to 1987, removed “We hope you will enjoy your visit” from the signs in 1982, hoping the revised message would attract new jobs and new residents to the state..

Public concern about the state of the environment was also embodied in federal laws passed, including the Multiple Use–Sustained Yield Act of 1960, the Wilderness Act of 1964, and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. All of these laws mandated environmental-protection measures that complicated federal timber sales in the coastal areas of Tillamook, Lincoln, and Curry Counties, which have large acreages of forestlands managed by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

By this time, too, tourism had blossomed into a major growth industry on the coast. The rising middle class in America had disposable income and leisure time, and tourists visited to the coast to play on the beach at Seaside, explore the cheese factory at Tillamook, fly kites at Lincoln City, eat fish and chips at Depoe Bay, camp at Beverly Beach, catch crabs off the pier at Newport, take the elevator down into the Sea Lion Caves north of Florence, watch myrtlewood being polished near North Bend, eat cranberry candy at Bandon, and fish for chinook salmon at Gold Beach.

The Oregon Coast also attracted affluent immigrants, permanent residents who wanted to live in an unspoiled natural environment and enjoy a small-town lifestyle. Many of the newcomers were retirees who brought their incomes with them and who, like the tourists, did not share longtime coastal residents’ familiarity with and dependence on logging and sawmilling. While those who live on the coast are far from unanimous in their opinions on the environment or anything else, the presence of visitors and newcomers who love the natural world and, not coincidentally, have no need to make a living from it has eroded public support for logging and lumbering, historically the region’s bread and butter.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Tom McCall (1913-1983)

This photograph shows Governor McCall visiting an Oregon beach on May 13, 1967, in the midst of a period of contentious, state-wide land-use rights debates. At a Junior …

Mark O. Hatfield (1922-2011)

Mark Odom Hatfield’s long career in Oregon politics began in 1951 when he was elected into the Oregon state legislature as the representative for Marion County. In 1955; …

Fight for the Beaches

Oregon Journal photographer Herb Alden took this photograph of Peter Frost (right) and an unidentified friend at an Oct. 28, 1968 rally in Cannon Beach. More than 200 …