Transition in the 1950s

Stewart Holbrook noted that the “pure logger strain” of industrial worker was threatened in 1938. By the 1950s, that threat became clear to the industry and the public. The war years were hard on the industry because of the pressure to cut despite the lack of skilled loggers. Klamath Falls mills that closed during the 1940s and 1950s included the Pelican Bay Lumber Company, the Lamm Lumber Company, and the Shaw-Bertram Lumber Company. In 1950, Shevlin-Hixon in Bend closed down, selling what remained of its holdings to Brooks-Scanlon. During the 1960s, the Lelco mill in Bend closed as well. Ironically, as some of the older mills began closing, the post-war building boom created a huge demand for lumber. New firms in other parts of Oregon attempted to meet the demand, but in central Oregon the industry’s capacity for primary lumber production reached its highest point in the early 1950s and then began a slow decline. By the end of the century, the only major mills operating were the Gilchrist mill in Gilchrist, the Ochoco Lumber Company mill in Prineville, and the Confederated Tribes mill in Warm Springs.

The decline in primary production during the late 1950s and 1960s is related to several phenomena. First, private timber holdings of the oldest firms were “cut out” during the late 1930s and the war years. This explains the demise in the 1950s of Shevlin-Hixon, Alexander-Yawkey, and some of the other traditional firms with private timber. National Forest timber was available, but many traditional lumber firms were unwilling to adapt to the competitive bidding practices and federal regulations that public timber sales entailed.

A second factor was the rise of secondary manufacturing. As millwork factories became more profitable in the 1960s and 1970s, they became more attractive to investors, diverting capital from primary production, which had lower profit margins than secondary wood products manufacturing. One veteran of the central Oregon lumber business, Brooks-Scanlon forester Ted Young, estimated that the millwork plants in Prineville, Redmond, and Bend were bringing more pine lumber into the area than the primary mills were producing by the end of the 1970s.

Finally, we see in the 1960s the beginnings of the nationwide move from primary industry to the post-industrial economy. In steel, fabric, shoes, and other basic industries, primary manufacturing moved to offshore locations while U.S. businesses concentrated on innovation, design, and retailing rather than manufacturing. In central Oregon, the post-industrial economic mix included tourism and recreation, retailing, professional services, and a limited amount of high technology.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

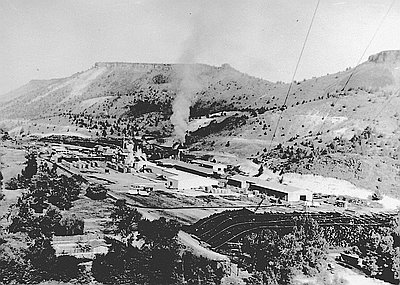

Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon Mills, Bend

This photo shows Bend, Oregon’s two largest lumber mills. The Brooks-Scanlon mill is on the far side of the Deschutes River, in the background of the photo; the …

Warm Springs Reservation Mill

In 1938, four years after the congressional passage of the Indian Reorganization Act, the Warm Springs tribes became officially incorporated as the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs …