The Mills

After their mills began operations in Bend in 1916, the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company and the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company, logged their way south, cutting out the timber of the Deschutes Valley, the Paulina Mountains, and northern Lake and Klamath counties. Shevlin-Hixon’s last logging operation took them to the northern border of the Klamath Indian Reservation in 1948. In 1938, Brooks Scanlon bought an extensive tract west of Bend from the family of James J. Hill. This land was originally part of the 830,000 acres of military wagon road grant lands that Hill purchased in 1906. Currently, in 2003, Brooks Scanlon’s successor firms continue to log this tract.

Like many other large pine manufacturers, both Brooks-Scanlon and Shevlin-Hixon were formed by entrepreneurs from the Great Lake states who moved into western pine regions during the 1890s. Shevlin interests were a major factor throughout the western pine industry, with mills in northern California at McCloud, and in Oregon at Pine Ridge and Bend. The United States Bureau of Corporations identified the Shevlin interests as one of the firms that had skirted the law by acquiring public timber through fraudulent means. The report also asserted that the Shevlin partners were closely associated with James J. Hill and the Northern Pacific Railroad group. In 1914, Shevlin’s U.S. holdings were concentrated in Oregon (213,000 acres), Montana (113,000 acres), and Minnesota (176,000 acres). The Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company and the affiliated Brooks-Robertson and Scanlon-Gipson companies had also acquired central Oregon holdings by 1914, but their activities did not attract the Bureau’s attention.

After their mills began operations in Bend in 1916, the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company and the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company, logged their way south, cutting out the timber of the Deschutes Valley, the Paulina Mountains, and northern Lake and Klamath counties. Shevlin-Hixon’s last logging operation took them to the northern border of the Klamath Indian Reservation in 1948. In 1938, Brooks Scanlon bought an extensive tract west of Bend from the family of James J. Hill. This land was originally part of the 830,000 acres of military wagon road grant lands that Hill purchased in 1906. Currently, in 2003, Brooks Scanlon’s successor firms continue to log this tract.

Like many other large pine manufacturers, both Brooks-Scanlon and Shevlin-Hixon were formed by entrepreneurs from the Great Lake states who moved into western pine regions during the 1890s. Shevlin interests were a major factor throughout the western pine industry, with mills in northern California at McCloud, and in Oregon at Pine Ridge and Bend. The United States Bureau of Corporations identified the Shevlin interests as one of the firms that had skirted the law by acquiring public timber through fraudulent means. The report also asserted that the Shevlin partners were closely associated with James J. Hill and the Northern Pacific Railroad group. In 1914, Shevlin’s U.S. holdings were concentrated in Oregon (213,000 acres), Montana (113,000 acres), and Minnesota (176,000 acres). The Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company and the affiliated Brooks-Robertson and Scanlon-Gipson companies had also acquired central Oregon holdings by 1914, but their activities did not attract the Bureau’s attention.

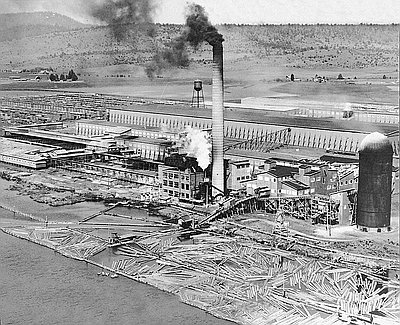

The larger of the two Bend lumber mills was owned by the Shevlin-Hixon Company. As the Bureau of Corporations report made clear, the “Shevlin interests” were a group of partners based in Minneapolis and active in the lumber business throughout the United States and Canada. The Shevlin mill in Bend provides an excellent case study of the pine industry in central Oregon.

The Shevlin partners created Shevlin-Hixon as a separate firm, incorporated in 1915, to begin building the super-mill at Bend. Although the United States would not enter World War I until 1917, the market for pine and other war material manufactured from pine was already strong in Europe.

The project was conceived on a grand scale. According to the Timberman, the main power was to be furnished by a 750-horsepower Corliss reciprocating steam engine, with three turbine-generators, providing electricity for the motors that ran the saws. The mill was to have a nine-foot double-band head-rig with a daily capacity of 300,000 board feet. Included in the plant would be a battery of twenty kilns for drying the best grade lumber. Lath and box factories would use lower-grade lumber. The Shevlin associates hoped that the mill would remanufacture 75 percent of its lumber into goods such as doors, windows, molding, boxes, and other finished goods.

In 1919, when the post-World War I market was still strong, Shevlin-Hixon cut ll0 million board feet, a prodigious amount of lumber. Only one other West Coast pine mill—the Red River Lumber Company at Westwood, California—exceeded that cut.

Railroad logging technology was a key component to Bend’s high productivity, and both Shevlin and Brooks-Scanlon were conceived as “railroad mills” from the outset. Shevlin’s logging operations included a broad-gauge railroad with Baldwin locomotives, Clyde four-line skidders, and a Lidgerwood machine.

These machines represented rather radical technology. After John Dolbeer’s invention of the donkey engine in 1882, West Coast logging had become increasingly mechanized. The vehicle for this mechanization was the skidder, which in Dolbeer’s version was simply a steam winch mounted on log skids. The skidder pulled the logs along the ground to move them from the point where they were felled to a point where they could be loaded onto rail cars or put into the water. Larger and faster skidders were possible when the machinery was mounted on a railroad car. The ultimate logic of this practice produced technology like the Clyde and Lidgerwood machines. These giant log skidders were larger than locomotives and could move logs along the ground or through the air at a startling pace—more than 1,000 feet per minute in some cases.

Shevlin-Hixon was one of the pine producers that used the expensive and complex railroad logging technology to its fullest advantage. The Clyde Company four-line skidder was described in the company's catalog as “the Clyde Self-Propelling Steam Skidding Machine.” It was able to move itself along the track, and then skid logs from 1,000 feet away at a speed of 500 feet per minute. The productivity of this machine impressed the pine loggers, and it became an industry standard for the largest operations during World War I. In 1918, a Clyde Company advertisement featured Shevlin’s four-line skidder, which had yarded 51,691,309 board feet during the 1917 season.

The McGiffert loader was another railroad logging machine that had widespread use in the pine country. The McGiffert was a rail-mounted crane that sat up on four legs above the rails. Empty cars could be advanced under it, loaded with logs, and then winched out of the way of the next empty car. The resulting operation was fast and efficient; indeed, the McGiffert machine outlasted all other railroad logging equipment, remaining in use through World War II and as late as 1954 on Weyerhaeuser operations in Klamath County. During the late 1920s steam-powered railroad logging gradually gave way to internal combustion technology as tractors, trucks, and motor-cranes replaced the large, cumbersome steam-powered equipment. The last log trains in central Oregon ended operations in December 1956.

Bend was emerging as one of the nation’s great pine production centers in 1916, and the two large mills dominated production. The logging and milling business in central Oregon was complex, however, with many smaller mills competing for a piece of the business. The Pine Tree Lumber Company, operating from 1917 until 1919 on the Columbia Southern canal near Bend, serves as an excellent example of these secondary firms. In 1917, the Timberman reported that the Pine Tree mill cut 7 million board feet during its first year of production. This was a respectable amount of lumber, but in the same year, Shevlin-Hixon cut 103 million board feet, and Brooks-Scanlon cut 65 million. How could a smaller mill compete with these giants for market, workers, or vital timber supply?

Mills like Pine Tree were able to stay in business because they sold their lumber to Brooks-Scanlon. As long as Brooks could sell more pine than it could produce, the added cut was welcome. In leaner times, of course, the larger mill would not buy lumber from its smaller competitors.

In effect, the large mills were so big that for the first few years of their operation, smaller mills could co-exist without problems. Indeed, the larger mills made their market muscle available to the smaller mills in an unusual symbiotic relationship. But the frantic market for lumber that followed World War I did not last. The Pine Tree mill was not rebuilt after it burned in 1919, and the other small mills ceased operations during the next few years.

In 1935, John Hudspeth brought his family-owned Hudspeth Lumber Company from Oklahoma to Camp Watson in eastern Crook County. The mill at Camp Watson shipped its lumber through Prineville and added facilities there in 1938 and 1940. In 1946, they built the first of several Hudspeth mills in Prineville. John M. Hudspeth became a major force in the lumber business of Oregon and the West during the middle decades of the century.

At the time of his death in 1983, the Oregonian estimated Hudspeth’s holdings at 1.3 million acres of timber and ranch land in Oregon, and seven pine mills in Oregon, Colorado, and Utah. His pine mills had a combined cut of over 1 million feet each day, and his ranches grazed 25,000 cattle. Besides lumber and cattle, Hudspeth’s other business interests ranged from hotels to a stained-glass studio in Portland. John Hudspeth’s activities in his business and personal life were the stuff of legend. His passion for businesses, gambling, aircraft, and fast cars was boundless. He was continually under investigation by the Internal Revenue Service after the 1950s. Oral sources report that Hudspeth relished his conflict with the federal authorities, and viewed his tax troubles as another high-stakes poker game.

The last mill to come to Central Oregon in the 1930s was run by the Gilchrist Timber Company in Gilchrist. Gilchrist operations had begun in New Hampshire, but relocated to Michigan by 1850. In the 1880s, they moved into Wisconsin, and then in 1907 opened a mill in Mississippi. By the 1930s, the Mississippi pine was cut out, and the family moved their operations to central Oregon, where they eventually acquired over 100,000 acres of timber holdings in Deschutes, Lake, and Klamath counties.

The Gilchrist mill was built in 1938, complete with a company town housing about 500 residents. The town and the central shopping mall were built with an eye to aesthetics. The Little Deschutes River was dammed to form a large mill pond. Houses were painted a uniform brown color. The attractive setting, expansive lawns, tennis courts, and mature ponderosa pines lent the whole setting a resort-like atmosphere.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company

At the time of this photo in 1941, Weyerhaeuser Klamath Falls employed approximately 1,200 men and produced 200 million feet of wood products each year. Weyerhaeuser experienced a …

Shevlin-Hixon Mill, Bend, Oregon

In 1916, the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company built a mill on the Deschutes River in Bend and began heavy cutting on more than 200,000 acres of company-owned ponderosa pine …

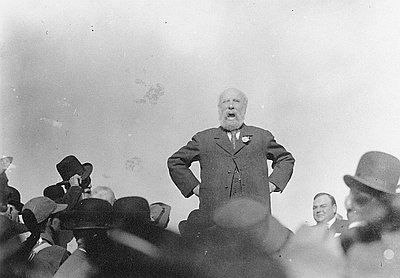

James J. Hill in Bend, 1911

This photograph of James J. Hill speaking in Bend was taken moments after he hammered the golden spike to complete the Oregon Trunk Railway on October 5, 1911. …