Tourism and Recreation

Judge John B. Waldo, an early visitor to the central Oregon Cascades, commented in a letter written on August 24, 1880, on the recreational potential that the area offered: “This evening we are all here—have had a fine supper—and my blankets are spread for the night within the same circle of trees and their grassy carpet which concealed me, and from which I fired my shots at the deer. Think of this, my friends in the Valley, and weep.”

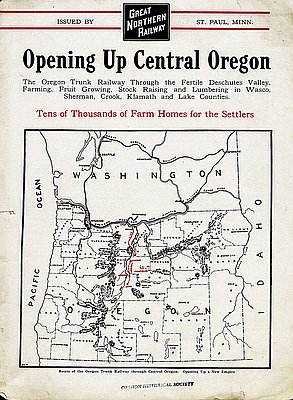

Waldo, perhaps unlike his “friends in the Valley,” was a gentleman of leisure who could afford extended outings in the high Cascades each summer. For most Americans, wilderness recreation was not available until rail and motor transportation made the central Oregon country accessible. Railroad access to central Oregon was available after the completion of the Oregon Trunk Railway in 1911, but highways across the Cascades lagged until the completion of Highway 26, the Wapinitia route near Mt. Hood, and Highway 22, the North Santiam route, in the 1930s. Additional highways linked central Oregon to the Willamette Valley, including the Willamette Pass (Highway 58), the South Santiam Pass (Highway 20), and the McKenzie Pass (Highway 126). Automobile tourism brought visitors to central Oregon to enjoy outdoor sports including fishing, hunting, mountaineering, and summer camping. The Pilot Butte Inn in Bend was an early destination for many visitors.

One of the first fruits of improved recreational access to central Oregon, ironically, was a clash between the recreationists and the lumber industry. In 1912, the Southern Pacific Railway had recently been completed to Kirk, a point forty miles north of Klamath Falls. Wealthy sportsmen from California journeyed by rail to the end of the line, which was located in the Klamath Reservation, along the Williamson River. There they were to go fishing in an unspoiled location. To their chagrin, they found Klamath County logger Milburn Knapp driving logs down the Williamson to his mill near Chiloquin. Since the Indian Service had sold Knapp the logs on the reservation, the Californians sued the Indian Service for spoiling their sport. The courts forced Knapp to abandon his contract.

As early as the 1950s and 1960s, capital from the lumber industry fueled the development of destination resorts. Prineville lumbermen John Hudspeth and Lee Evans began the Sunriver development in the 1950s, eventually selling to Portland developer John Gray. During the 1960s Brooks-Scanlon formed Brooks Resources, a land development subsidiary which developed several recreational properties including Black Butte Ranch. Bend lumberman Leonard Lundgren developed House on the Metolius, a resort community near Camp Sherman. Other lumber interests including the Stevenson family from Stevenson, Washington, and the Wendt family from Klamath Falls have been heavy investors in central Oregon resorts and recreation businesses.

Winter sports in the Cascades began with the Scandinavian lumber workers who came to central Oregon from the Great Lakes States and from Europe. Lumber workers Nels Skjersaa, Emil Nordeen, Nils Wulfberg, and Chris Kostol are credited with forming the Bend Skyliners mountaineering club in 1928. Both Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon nurtured the Skyliners since their employees were active in the club, and the club had a major presence in the community. Brooks-Scanlon publicist Paul Hosmer even provided the name “Skyliners.” The Skyliners sponsored races, conducted mountain rescues, and promoted competitive skiing.

During World War II, Americans learned a great deal about European mountaineering through combat in the Alps. The Army created the 10th Mountain Division as an elite force of ski-troopers. Veterans of this organization influenced the winter sports business throughout the United States after the war. One of these men was Bill Healy, who had skied in the Cascades prior to his service with the 10th Mountain Division. Healy moved his furniture business from Portland to Bend and became active in the Skyliners. In 1957, Healy and other investors began developing a ski area on Bachelor Butte.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Bachelor Butte ski area prospered through good management and consistently good snow conditions. Competitive skiers from other parts of the United States discovered Bachelor Butte as an excellent training area. The Skyliners program prospered as well, training local skiers to become prominent national and international competitors. Frank Cammack, Skyliners coach and Brooks-Scanlon lumber broker, nurtured the early careers of Olympic skiers KiKi Cutter, Jean Saubert, Mike Deveka, and others. The increasing visibility of central Oregon as a recreation area drew new residents and businesses. Bend’s population grew from 15,000 in the mid-1970s to 50,000 by the end of the century, making Deschutes County one of the fastest-growing counties in the West.

© Ward Tonsfeldt and Paul G. Claeyssens, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

Shevlin-Hixon Mill, Bend, Oregon

In 1916, the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company built a mill on the Deschutes River in Bend and began heavy cutting on more than 200,000 acres of company-owned ponderosa pine …

Brochure, Opening Up Central Oregon

In 1911, laborers completed the Oregon Trunk Railroad from the Columbia River, near Celilo Village, to Bend, giving large timber companies a way to export timber from the …

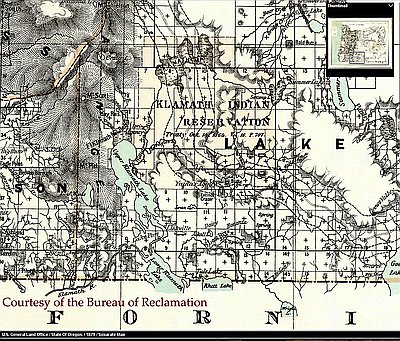

Klamath Indian Reservation

When white explorers entered the Klamath Basin in the 1820s, the Klamath Indians occupied the Upper Klamath Lake area, which included Klamath Marsh and the Sprague and Williamson …