Epilogue

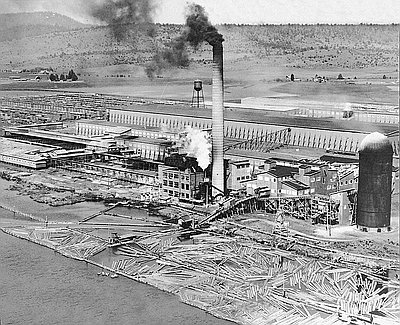

Despite the plans of the New Urbanists, the shift in the region’s industrial base to electronic technology has induced the outward flow of population. Between the mid-1950s and the early 1980s, 60 percent of the logging jobs in Oregon disappeared, because lumber companies developed forests in the southeast closer to the expanding cities of the Sun Belt, and because many remaining timber mills have become automated through the use of computers. By 1980, over three times as many people in Portland manufactured electrical machinery as worked in timber mills. Older corporations like Oregon Steel and Willamette Industries remained downtown to utilize the Port, but the new electronics companies sought inexpensive land in the suburbs.

The electronics industry grew slowly after World War II from the technical innovations of local entrepreneurs like Howard Vollum and Jack Murdock. Their new oscilloscopes became the core of a varied business which they called Tektronix, Inc.. By 1957, they acquired a larger property west of Beaverton to project a business vision, largely borrowed from Hewlett-Packard, of a “campus” that combined expanded research facilities with production. Tektronix also pioneered for Oregon-based firms by opening plants in countries like Ireland and Japan, and selling their products around the world. By the early 1980s, with the collapse of employment in the timber industry, Tektronix became the largest private employer in Oregon. The arrival in 1976 of Intel, the world’s leader in developing memory chips and integrated microcomputer systems, gave the Beaverton area visibility as a national site for high technology. Washington County provided Intel with open land, water, cheap power, and a good social environment for employees. The Japanese, with about one-third of their firms in computers and electronics, have been the most numerous of foreign companies investing in the Portland area. Between 1984 and 1986, NEC, Epson, and Fujitsu each bought sites of 120 to 210 acres in the Hillsboro area, for the same reasons as had Intel.

Changes in federal immigration laws starting in 1965 allowed people from countries formerly excluded to come to the Portland area to find work or start businesses. Portland at first received very few of the newcomers, but after the arrival of Japanese firms migration from East Asia and Mexico has accelerated. In 2010, after two decades of very rapid growth, Portland remained 76 percent white, and the African American population reached 6.3 percent of the total. During the 1990s the Asian population increased by 50 percent and the Hispanic population tripled. In 2010, Asian Americans constituted 7.1 percent of Portland’s population. The Hispanic population continued to grow, reaching 9.4 percent in 2010. The metro area supported a larger Hispanic community, with 16 percent in Washington County and 8 percent in Clackamas County.

In Clackamas County, Asians comprised 3.9 percent of the population, nearly double that in Washington County, with 6.9 percent. The city has acquired the trappings of Pacific Rim sophistication with more Asian landmarks. Hyundai has built a shopping plaza in the Beaverton area, and many Korean small businesses have opened food stores throughout the region. Sapporo, the sister city with which Portland’s officials have cultivated the most intense contacts, has contributed a friendship bell at Portland’s new convention center, a garden at the Japanese Garden in Washington Park, a musical sculpture at Waterfront Park, as well as hundreds of millions of dollars annually in trade.

Portland’s most heavily capitalized and visible new company is the athletic shoe manufacturer, Nike, organized in the mid-1960s by Phil Knight and the late Bill Bowerman, former track coach at the University of Oregon. It has virtually created a new market by persuading young women and men to reevaluate how they use shoes. It neither manufactures nor pollutes in Portland, but draws income to it from all over the world. At its sprawling “campus” in Beaverton, Nike conducts research and marketing, based on slogans, symbols, and on highly paid endorsements from American athletes with international appeal. Like the electronics companies, however, Nike utilizes the amenities of the suburbs. During the 1990s as Portland’s population grew by 21 percent, Beaverton grew at double that rate.

Symbolic of Portland’s new cache was the announcement on October 1, 2002, that Air China Cargo would initiate a non-stop service between Portland and Shanghai. The major users in the Metro area would be Nike, Tektronix, Intel, Epson, and InFocus, all of which had plants in China. To celebrate the new connection a ceremony was held at the new Classical Chinese Garden at NW Third Avenue and Everett Street. Governor John Kitzhaber, Mayor Vera Katz, and representatives of China Air Cargo, Nike, and the Port of Portland spoke. But what seems like another profitable link to the Pacific Rim economy also reveals the vulnerability of a city whose major firms see it as a transit point for production and sales elsewhere. Despite Portland’s innovations in regional governance, imaginative land-use planning, and captivating public architecture, the demands of new technology draw people to the periphery while its ties to the global economy make it more vulnerable to dislocations abroad.

Portland at the beginning of the twenty-first century has developed new international connections and a new social complexion. Its economy has shifted from processing and shipping regional raw materials to producing consumer electronics, designing new apparel, and moving Asian automobiles for sale across continents. It relies as much on an expanded airport as on a revitalized port, and its population has become more racially diverse and more suburban than ever. The metropolitan region of which the city sees itself the focus exists not merely in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, but on the northeast rim of the Pacific Ocean. Indeed, the demands of the Pacific Rim economy challenge the vision of the urban reformers, who in the 1970s saw a revitalized downtown as the region’s civic priority.

Though journalists covering Portland’s architectural revitalization and light rail experiment did not notice, key changes at the Port were intended to reposition the city in the world economy. In the 1960s, the Port rejected new containerized loading facilities because its traditional agricultural and timber exports did not require the new technology. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Port utilized what it did have—reasonable leasing rates and its unique railroad connections through the Columbia River Gorge to the Middle West—to induce Japanese auto companies to make Portland a bridge to mainland sales venues. Honda and Toyota, in conjunction with shipping companies, built specialized ships called “pure car carriers” to utilize port facilities. The process of unloading cars from these carriers and then reloading them onto railroad cars or trucks for distribution created thousands of jobs for longshoremen and teamsters, while ports turning to containerized operations lost these unionized jobs.

For the auto companies, however, the Port of Portland was only part of an evolving production and marketing strategy, to which port officials had continually to adjust. As American demand for Hondas and Toyotas grew, each company opened production facilities in the United States, so the port sought smaller firms like Subaru and the Korean conglomerate Hyundai to utilize available facilities. As other commodities shipped through the port, especially grain and containers, have declined, the flow of Asian autos grows steadily. By 2002 Portland had become the largest auto handling port on the Pacific coast. As of 2014, it was the second largest auto gateway on the West Coast and fifth largest in the U.S. Ultimately, however, the utilization of the port’s facilities depends on the global strategies of the Japanese and Korean companies and on the health of East Asian economies to which most exports go. The airport, over which the Port gained jurisdiction in the 1930s, was at first a small part of its operations. But since 1970 the airport has added runways and became a hub for Alaska Airlines and Horizon Air, as well as for airlines handling freight. Direct flights to Tokyo and Amsterdam service the city’s new business connections.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company

At the time of this photo in 1941, Weyerhaeuser Klamath Falls employed approximately 1,200 men and produced 200 million feet of wood products each year. Weyerhaeuser experienced a …

Tektronix's Sunset Plant

This photograph depicts Tektronix's plant at Sunset Highway and Barnes Road. The oscilloscope manufacturer moved to this new, state-of-the-art facility in 1951, having outgrown its plant on Hawthorne …