City Planning and Civic Engagement

As the mercantile elite lost control of the electoral process and saw local government, including the schools and courts, focus on unfamiliar social concerns, they were appointed to various boards that channeled growth. By 1920, the elected commissioners no longer made key political decisions but pursued goals promoted by advisory commissions and administered by a civil service bureaucracy. The Commission of Public Docks, the Planning Commission, the Port of Portland, and the Civil Service Board seem to have superseded the elected officials as formulators of public policies.

Initial demands for civic improvement in America’s major cities had many motives, but they focused initially on the pragmatic goal of providing supervised space to occupy children after school hours. In 1907, the Portland Park Board, established by the legislature in 1900, led a successful campaign to pass a bond issue designating a million dollars to acquire parkland and to open playgrounds. By 1913, Portland had fifteen parks and thirteen playgrounds and had widened a few access streets into boulevards. But it still had fewer acres of parkland per capita than Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. The more powerful argument for planning came from business leaders who saw that the opening in 1914 of the Panama Canal would create substantial growth for West Coast cities. Through formal planning, they hoped to impose some order on their metropolis by revitalizing the central business district for government, shopping, and commerce, while widening arterial streets to middle-class suburbs. The rebuilt civic core and an improved street railway system should also instill a sense of unity among the various ethnic groups in the city and among trade unionists and businessmen in their neighborhoods.

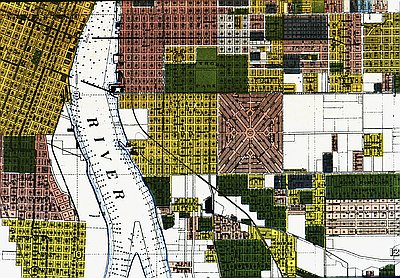

In 1912, a year before Portlanders adopted their new commission form of government, they also approved a plan proposed by E.H. Bennett, formerly an assistant to Daniel Burnham, the Chicago city planner. The plan emphasized the usual riverfront and perimeter parks, with boulevards connecting them to a fringe of greenery around residential and commercial areas. The Bennett Plan was to be a general guide for the city council when approving the sites of large buildings, widening streets, and acquiring parks. Adopting the plan as a guide did not cost the voters any money, while providing the vague assurance that the city’s growth would be orderly. Portland was the only major city on the West Coast to adopt such a plan, because its business community supported its general outline and labor unions did not oppose it; but the city council never acted on the Bennett Plan, because local property owners could not agree on how its proposals would affect their values.

By December 1918, Portland’s commissioners had created a Planning Commission of seven citizens and ex-officio members, including the mayor, the city engineer, and the city attorney. With J.P. Newell, a prominent civil engineer, as its president, the commission focused on transportation, widening streets, and zoning to place general limits on property uses. In 1924, voters approved a minimal zoning code and imposed modest height and density controls. As population grew, especially on the east side, the city and Multnomah County continued to generate substantial public debt to widen and repave streets, build bridges, and add miles of sewer lines. Aside from occasional acquisition of small parks, civic amenities like Skidmore Fountain and the Benson Bubblers left a modest legacy of private philanthropy.

Public schools expanded to cope with population growth, to some degree to accommodate immigrant diversity and especially to embody the view that teaching was a professional undertaking that should impart specialized skills. By 1912, the school district responded to a population that had more than doubled in a dozen years by organizing a modern system. A few rural schools remained open with one or two teachers; but most staffs, like those at the Failing School in South Portland and the nearby Shattuck School (the former Harrison Street School) had twenty or more teachers. Reflecting new compulsory attendance laws, two neighborhood high schools, Washington and Jefferson, were built on the east side. In response to demands by labor unions, a School of Trades was created in the old skilled working-class neighborhood two blocks north of Weinhard’s brewery. The school district also employed twenty-nine “special teachers,” primarily in manual training and sewing, who may have alternated between schools. The people of Portland, however, did not express an interest in publicly financed higher education, which was left to small private colleges like Reed (1911) and the University of Portland (1901).

The most inexorable change in Portland during the 1920s was the expansion of housing on the east side, were eventually 70 percent of the city’s population would live. The construction projects that created union jobs and the absorption of the middle class in expansion, may have helped dispelled the fears that had garnered support for the Ku Klux Klan’s and its racist and xenophobic platforms. In the process of expansion, Portland became absorbed in the cult of the automobile. Platted areas like Ladd’s Addition and Irvington were filled in, and fifty square miles of rural land were absorbed for suburban home construction. To encourage outward migration, the city passed unprecedented bond issues to build bridges at Sellwood and Ross Island and at Linnton, north of the city. The city also paved miles of eastside streets, widening for the first time arterials like Sandy Boulevard, Division Street, Powell Boulevard, Foster Road, and Southeast 82nd Avenue. Property values in new neighborhoods were enhanced with small recreational parks for baseball, tennis, and swimming.

As in all large West Coast cities, the automobile became both the means and the focus of growth. Los Angeles received most attention because of its spectacular sprawl, but residents of Seattle, San Francisco, and Portland bought automobiles in almost as high a proportion. Showrooms sprang up on major downtown streets, including Morrison, as well as along north Broadway from Burnside to Union Station and across the bridge along east Broadway. By the mid 1920s, eight hundred filling stations employed twenty-four hundred men in the city, and auto repair shops dotted residential neighborhoods. The city council refused to follow the Planning Commission’s expensive recommendation to widen downtown streets, though the police did require the posting of stop signs at major intersections.

Across most of the United States in the 1920s, electricity replaced steam as the power source for industry and replaced coal as the source of heat in new homes. During the 1920s, the consumption of electricity by the average Portland home grew by 250 percent. The largest utility, renamed the Portland Electric Power Company (PEPCO), expanded its generator facilities and became a retailer by opening stores to sell new lines of appliances like stoves, washing machines, and radios that induced consumers to buy its power output. The proliferation of automobiles, however, meant that the transportation side of PEPCO’s business suffered.

As ridership on streetcars declined, PEPCO turned to a new technology, the bus. The Oregon City Motor Bus Company ran between Portland and Oregon City, and by 1925 it had added five bus feeder lines on the east side. As interest rates rose, however, it contracted heavy debts and was absorbed by a Chicago utility holding company. When power consumption as well as trolley and bus ridership contracted during the early years of the Depression, the combination of debts and stock manipulation by the holding company forced it to file for bankruptcy. Local stock holders lost savings, and the Portland economy fared no better than its key utility. Bewildered leaders of the self-promotional metropolis faced the long depression of the 1930s, with little hope of finding a quick remedy.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Union Station, 1913

Union Station, shown here in 1913, opened in 1896 after several delays. It was one part of Henry Villard’s grand vision for Portland. Villard wanted to make Portland an …

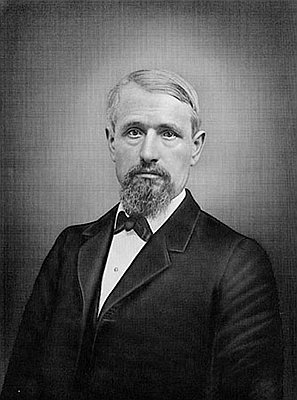

Henry Weinhard (1830-1904)

Best known for his internationally renowned lager, Henry Weinhard was among the successful businessmen in the early years of Portland. His influential role in developing Portland's economy and …

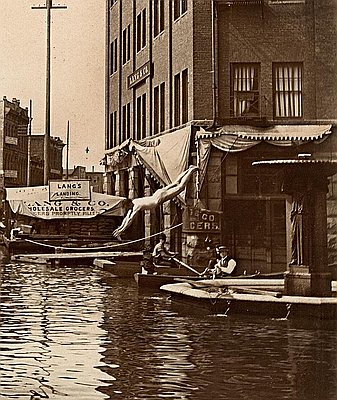

Skidmore Fountain and Stephen G. Skidmore

This photograph shows an unidentified man diving into waters surrounding the Skidmore Fountain during the Willamette River flood of 1894. The fountain, located at the intersection of First …