Portland's Laboring Class

As a frontier city, Portland had always had many more adult men than women. The young men were usually unmarried and accustomed to moving from rural to urban work according to the seasons. During the spring and summer, they worked in the woods felling trees and building railroad spurs that connected forest sites to the main lines. They also worked in the mines or on farms planting, irrigating, and harvesting wheat or flax. As the rains ended, rural work for the winter, the men would move into Portland to excavate and plank streets, construct buildings, or work as general laborers.

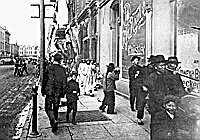

Boarding houses on the edge of the central business district provided shelter for lower income people whose stay in town would be indefinite. As early as 1865, the city directory found 763 people, about 20 percent of the adult population, registered at hotels and boarding houses. Some must have been traveling salesmen, but the assumption is that most were male laborers. Gradually, they clustered just north of Burnside Street, from Second Street to the Park blocks, finding their entertainment in vaudeville houses, beer gardens, and saloons. The unattached men created income for pool halls, frequented saloons and their brothels, and became the focus of law enforcement. They also filled the city’s treasury, because license fees, especially for the saloons, provided the bulk of the city’s regular income.

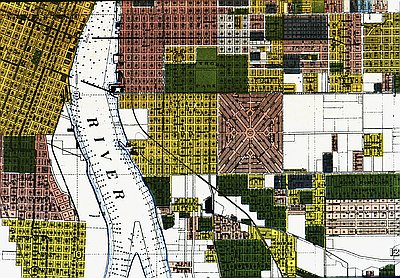

The police now believed that Portland had become a real city, with its own criminal district to patrol. In 1880, most crimes were committed in a corridor from D Street on the north to Morrison Street on the south, and between Fourth Street and east Oak, with the heaviest cluster between A and Stark Streets. Of those arrested, 25 percent were of Irish birth; 5 percent were Chinese.

Portland’s center for prostitution was just south of the designated high crime area, on Third Street near Yamhill. A string of twelve small houses was interspersed between numbers 110 and 191 along Third, with five additional houses along Yamhill between First and Third Streets. All fifty-eight women listed as prostitutes in the 1880 federal census were white, and almost two-thirds were age twenty-five or younger, including thirteen teenage girls. Many of the prostitutes were attended by young Chinese men, who cooked, ran their errands, and took their sheets to nearby laundries. Prostitution was accepted as part of downtown life by the wealthiest real estate investors, who owned the properties on which the houses were located. Harold Hirsch, the great nephew of Jeannette Meier, recalled that the department store considered the prostitutes among their most reliable customers for linens, because they always paid in cash.

In the 1880s, workingmen with more specialized skills—printers, typesetters, bricklayers, longshoremen, and carpenters—organized themselves into craft unions. The largest union, Portland Local No. 50 of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, was organized in September 1883, just after the Northern Pacific Railroad arrived. Most craft union members had different social characteristics from those on the wageworkers’ frontier and tried to differentiate themselves from the transients. Union members were usually married with families; and as east Portland expanded after 1900, they bought small homes near the many machine shops and railroad yards. As Craig Wollner observed for the carpenters unions, the men organized to ensure the life and health of their members and to improve working conditions and wages. To protect their interests, unions in 1885 led the agitation to exclude Chinese. Perhaps symbolic of their sense of labor as a fellowship was the inclusion of eight craft unions in the 1891 city directory’s list of “Societies and Clubs.” The carpenters and printers were listed with the Turnverein, the Portland Humane Society, the YMCA, and the elite Arlington and Concordia clubs.

Craft unions, which had no legal standing and whose membership fluctuated, had to select crucial moments to make demands on their employers. As the economy expanded in 1890 after several years of recession, the two carpenters unions in Portland joined a national strike for an eight-hour workday and a closed shop. The Portland Builders Exchange, a coalition of their employers, rejected these demands. But by May 1, other unions joined the strike, held a huge May Day rally, and forced concessions from the builders.

Union membership declined during the depression in the mid 1890s. In 1894, the Central Labor Council helped enroll the unemployed in a troop affiliated with the so-called army of Jacob S. Coxey, who wanted men to go to Washington, D.C., to petition Congress to put men to work. The leader in Portland was J.M. Schier, a stonemason who had the continual support of the longshoremen, carpenters, and others. The unions held public rallies urging men to sign up at a stand at Third and Burnside. By April, the organizers had enrolled over 400 men, most of whom were craftsmen temporarily out of work and desperate to care for their families. On April 27, about five hundred men marched to Troutdale and the next day seized a train to take them east. Since they had now broken the law, they were intercepted by federal troops just beyond The Dalles. They surrendered peacefully and were returned to Portland. A trial, accompanied by downtown rallies with over 1,000 supporters, led to their apologies for breaking the law and to their release. While the exit of Coxeyites from Portland has not been traced, most apparently left on eastbound freights in groups of from ten to twenty-five men.

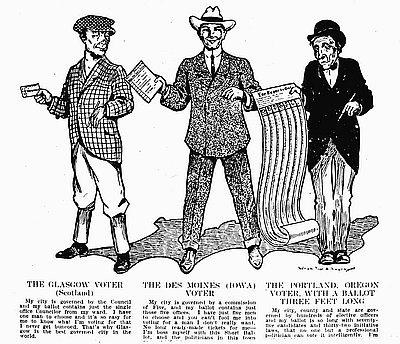

Politically, Portland’s unions followed the philosophy of Samuel Gompers, the national president of the American Federation of Labor who visited Portland several times to help reorganize the unions into a central labor council. Skilled workers clung to a mentality that emphasized the tangible brotherhood of the craft over the more abstract view that workers might have a common class interest, such as that expressed by Socialists or the Industrial Workers of the World. The craft unions had no radical political goals that might require a separate labor party or a Socialist state, but by 1908 they had sufficient political influence to require that the city hire only union labor for the construction of its bridges, water mains, and buildings. In Oregon, organized labor joined the middle class by supporting reforms in the political culture rather than in the economy. The new State Federation of Labor made no unique demands, but supported the reforms of the electoral process proposed by William U’Ren, Jonathan Bourne, Will Hayes, and Harry Lane: the initiative, the referendum, the direct primary to nominate candidates, the direct election of United States senators, and the regulation of utilities so costs to consumers would remain low.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Oregon System Cartoon

This political cartoon from Joseph Gaston’s Centennial History of Oregon depicts a befuddled Portland voter holding a lengthy ballot in one hand standing next to two other men …

Irish Immigration

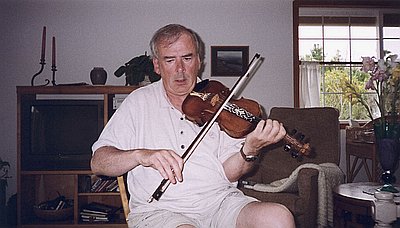

This photograph of Tommy McCreesh playing an eighteenth-century Irish fiddle in his Florence home was taken by Revell Carr in July 1998. Carr also interviewed McCreesh as part …

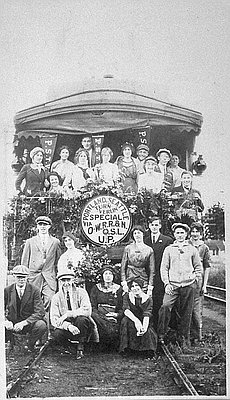

Portland-Seattle Turnverein Special Train

The Portland Turnverein was the local chapter of the German American athletic (gymnastic) association. Turnverein, coined after the German word turnen, or physical exercise, was the name given …