The Postwar Economy

As the wars in Europe and Asia slogged toward their bloody ends, federal and state officials turned their attention toward the postwar economy. With the Great Depression a recent memory, “reconversion” became a popular buzzword for public officials, journalists, and especially development groups who stood to benefit from the shift to a peacetime economy.

Oregon’s Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission, first appointed in 1944, published monthly suggestions to help draft a blueprint for the state’s future. Much of the commission’s attention focused on the federal government’s role in building the huge dams planned for the Columbia and Snake Rivers and the smaller but significant Willamette Valley Project. Its monthly releases praised the reclamation plans for the middle Deschutes region, the Klamath Basin, and the Ontario and Umatilla districts of eastern Oregon.

The most impressive phenomenon of the postwar era was the booming home construction industry, a direct consequence of wartime savings, deferred home purchases, and a growing population. Oregon newspapers confirmed a critical housing shortage as veterans began returning home and placed strains on available living spaces. In central Oregon, Bend city officials held hearings shortly after the Japanese surrender to discuss the local construction program. The city’s immediate postwar problems were similar to those experienced by cities and towns elsewhere in the state. Medford, Salem, Coos Bay, and Pendleton all reported a housing shortage as their community’s most pressing problem.

During the war years, Portland and its suburbs—including Vancouver, Washington—gained more than 250,000 residents. Oregon’s growth rate for the 1940s was nearly 40 percent, or 432,000 people. At the peak of wartime production in early 1944, approximately 140,000 defense workers lived in the Portland metropolitan area. The state's population was becoming increasingly skewed toward urban areas, especially in the Willamette Valley. While every western Oregon county gained population during the 1940s, four eastern Oregon counties—Baker, Gilliam, Sherman, and Wallowa—experienced losses. By 1950, nearly half the state’s population lived in the greater Portland metropolitan area, a trend that would accelerate during the second half of the century.

Rural areas experienced significant change despite the declining farm population—from 258,751 in 1940 to 221,399 in 1945. Farm families took full advantage of modern technology, and by the end of the war more than 75 percent of farms had electricity, 40 percent had telephone service, 90 percent had at least one motor vehicle, and 89 percent had radios. Farmers and ranchers purchased electrical pumps, cream separators, and milk coolers, and they wired their homes and barns with electricity. Consumers in both urban and rural areas purchased refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, toasters, washing machines, irons, radios, and other electrical appliances that were popular in a region with inexpensive power rates because of hydroelectric dams. Oregon’s domestic and commercial energy consumption would soar in the next two decades, as the Bonneville Power Administration and public and private utility firms promoted the use of electricity.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

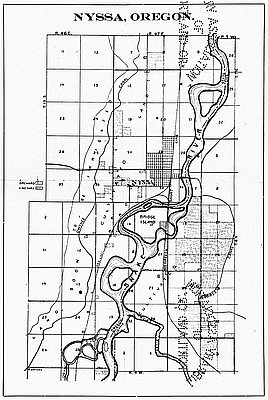

Facts about Snake River Valley at Nyssa, Oregon

This map is from a circa 1911 brochure promoting the “progressive and growing city” of Nyssa, located in northern Malheur County on the Idaho state line. The brochure …

Medford, Gateway to Crater Lake

Prior to the 1910s, most travelers to Crater Lake went by horse-drawn wagon, taking a full three days to cover the eighty-five miles from Medford. That began to …

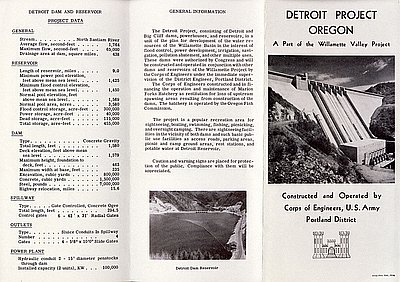

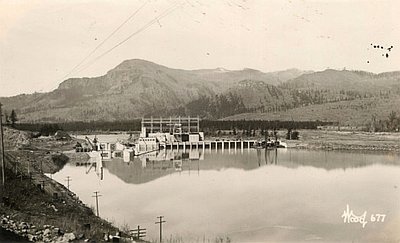

Detroit Project, Oregon

In the early 1930s, Willamette Valley business owners, residents, and politicians worked together to convince the federal government to develop a comprehensive plan for managing the Willamette River …