Forest Products and Agricultural Goods

Until the development and expansion of the high-tech industry in the 1980s, Oregon’s economy remained heavily dependent on exporting forest products and agricultural goods. Despite occasional downturns in the lumber market, the state’s timber-dependent communities prospered through the immediate postwar era. Towns such as Bend, Coos Bay, Roseburg, and Grants Pass experienced small housing booms, merchants carried on a lively retail trade, and newspapers praised Oregon for being the nation's top lumber producer.

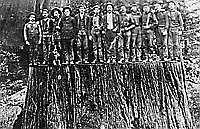

With a heavy demand for lumber, especially to supply California’s frenzied construction industry. With the use of incredibly efficient technology, timber harvests increased dramatically, from 5.2 billion board feet in 1940 to a postwar high of 9.1 billion board feet in 1955.

In keeping with the technological optimism of the postwar period, the lumber industry boasted that it practiced scientific forestry and treated timber as a crop. Intensive forest-management practices became the buzzwords of the day. If there was an ideological center to forestry practices, it was vested in sustained-yield management, a fuzzy concept subject to endless interpretation. Oregon newspapers extolled the benefits of sustained-yield, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administered the revested Oregon and California (O&C) railroad grant lands under the Oregon and California Sustained-Yield Management Act (1937). The BLM’s acres of land in Oregon are remnants of the nineteenth-century O&C land grant that reverted to the federal government when a successor company—the Southern Pacific Railroad—violated terms of the original grant.

The O&C legislation, according to its supporters, would protect local communities from timber exhaustion and provide for a stable and settled economy. Roseburg, in the heart of the timber-rich Umpqua district and with numerous sections of O&C timber, stood at the threshold of a production boom, according to the Roseburg News-Review. “On a sustained yield basis,” Charles Stanton enthused, “Douglas County had a most outstanding advantage.”

In retrospect, eligible counties became dependent on O&C revenue in lieu of county taxes. With the decline of timber production on federal lands after 1990, the timber-based payments to counties with O&C lands diminished steeply, bringing a crisis in public funding in the early twenty-first century. The loss of timber payments forced some counties in southwestern Oregon to cut funding for libraries, public safety, and other services.

Although the heaviest volume of timber harvesting in Oregon took place in the Douglas-fir region west of the Cascade Mountains, there were sizable centers of production in the central and eastern parts of the state, especially in the great ponderosa district that extended from Bend to Klamath Falls. The Brooks-Scanlon and Shevlin-Hixon mills operated two shifts a day, and timber harvesting boomed in the greater Bend area. To speed the movement of logs to Bend, Brooks-Scanlon extended its railroad past the town of Sisters to Black Butte, and the company resettled its large mobile logging camp in the same vicinity. Shevlin-Hixon moved its huge portable logging camp of some 350 people to a location adjacent to huge timber stands about ten miles southeast of Chemult in Klamath County.

Pine production neared record levels and central Oregon’s economy prospered as people flocked to the area. As the 1940s came to a close, however, rumors began to circulate that the Shevlin-Hixon mill would close because of dwindling log supplies. On November 21, 1950, the Bend Bulletin announced in bold headlines: “Shevlin-Hixon Sells to Brooks-Scanlon.” The sale included the firm’s timber, production facilities, and logging equipment. With the sale, 850 people lost their jobs, 225 in northern Klamath County and 625 in the Bend area.

As early as 1934, U.S. Forest Service Chief Ferdinand Silcox had reported that the two Bend mills were cutting far beyond a sustainable capacity. Shevlin-Hixon’s closing, however, did little to slow harvests of the remaining old-growth ponderosa pine. Production at the sprawling Brooks-Scanlon complex along the Deschutes River continued at a high level amid indications that the privately held stands were diminishing. Beginning in the 1950s, company loggers began cutting the commercially less valuable lodgepole pine to extend its supplies. At the same time, the firm reported increasing operating expenses because of the costs of hauling timber over long distances. It was obvious to many that the heavy cutting on company land was taking its toll.

The Bend story provides a striking example of the transition of an extractive and processing economy to an economy based on outdoor recreation—that is, on selling central Oregon’s natural beauty to visitors. In 1960, Bend was a small but thriving town of about 12,000, and its mill would continue to turn out a large volume of pine lumber for more than two decades. At the same time, however, winter sports venues and destination resorts were becoming more important to the regional economy. Black Butte, Sunriver, and the Inn of the Seventh Mountain were the first of several vacation retreats to appear in the greater Bend area.

By the time its timber supplies were gone and Brooks-Scanlon had closed its mill in 1992, Bend had an expansive, fashionable, and prosperous economy, and its survival depended on upscale winter and summer recreation and a new generation of telecommuters and retirees. The influx of relatively affluent newcomers to central Oregon also brought sharp increases in service-sector employment and growing disparities in wealth, characteristics of new economies everywhere in the West.

Not all former lumber towns made the transition so smoothly into the twenty-first century. The Coos Bay area on the southern Oregon Coast is a case in point. For more than thirty years after World War II, the healthy California lumber market brought prosperity to southwestern Oregon as new mills opened, small operations multiplied, and workers flocked to the Coos district. In 1947, the Oregonian proclaimed Coos Bay the “Lumber Capital of the World.” Locals referred to those years as “the great boom,” a period of heady optimism and abundant jobs. Even during the winter, when companies cut back their work force, everyone expected that slackening rains in the spring would bring good-paying jobs.

In the midst of the record-setting production, however, there were warning signs as employment in the forest products industry began to decline after 1960. Improvements in mechanization, mergers, and an increase in capital investment meant fewer loggers and mill workers in the Pacific Northwest. Although economic conditions remained relatively stable on the Oregon’s south coast through the 1960s and early 1970s, there were worries about depleted timber inventories, and loggers had to travel farther to and from work.

By the mid-1970s, jobs were becoming harder to get. Then came the whirlwind—a rash of layoffs and mill closures in 1979 led by the Georgia-Pacific Corporation’s plywood operation, one of the largest employers on Coos Bay. What followed over the next few years was a hemorrhaging of well-paid industrial jobs, as one mill closure followed another. Coos Bay gained a new reputation as the state's most depressed area.

Coos Bay communities were pacesetters for mill closures everywhere across the Northwest during the 1980s. Even when a few mills reopened, they did so with new automated equipment and sharply reduced workforces. A stagnant forest-products market, mechanization, and sharply diminished timber stands continued to erode Coos Bay’s industrial base. Except for retirement settlements, the south coast economy has continued to experience economic hard times.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Oregon and California Railroad

The Oregon and California Railroad (O&C) was the first railroad to connect Oregon with California. Construction of the line began in Portland during the spring of 1868. Under …

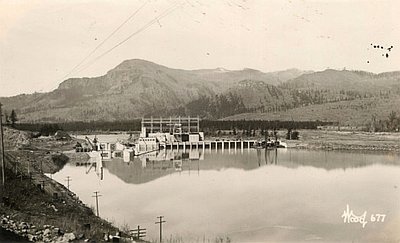

Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon Mills, Bend

This photo shows Bend, Oregon’s two largest lumber mills. The Brooks-Scanlon mill is on the far side of the Deschutes River, in the background of the photo; the …

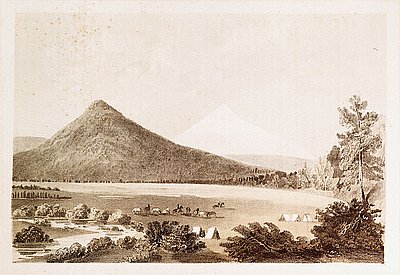

Mount Jefferson & Black Butte

This lithograph is based on an original watercolor by Robert S. Young, the artist who accompanied the Pacific Railroad Survey of 1855 commanded by Lieutenants Robert Stockton Williamson and Henry …